Parts of the Grape Vine: Roots

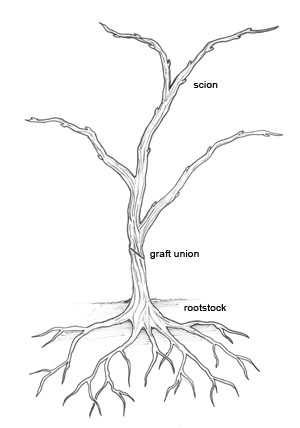

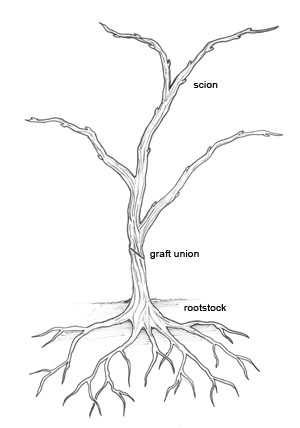

Fig. 1

Grafted vine, showing rootstock, scion, and graft union.

Grapevines

can be grown on their own root systems (own-rooted or self-rooted

vines) or they may be grafted onto a rootstock. A grafted vine consists

of two parts, the scion variety (e.g., Pinot noir), which produces the

above-ground parts (trunk, shoots, and fruit), and the rootstock

variety (many of which are often numbers, e.g., 101-14), which provides

the root system and lower part of the trunk. The position on the trunk

where the scion and rootstock are joined by grafting grows together and

is called the graft union. Successful healing of the graft union

requires that the vascular cambium of both the rootstock and scion are

in contact with each other, since these are the only tissues having

meristematic activity necessary for the production of new cells to

complete the graft union. Healing of the graft union often results in

the production of abundant callus tissue (a wound healing tissue

composed of large thin-walled cells that develop in response to

injury), often making the area somewhat larger than adjacent parts of

the trunk. Because rootstock and scion varieties may grow at different

rates, trunk diameter can vary above and below the graft union.

Why use rootstocks?

Rootstock varieties were originally developed to provide a root system for Vitis vinifera

L. (“European” winegrape) varieties that are resistant or tolerant to

phylloxera, an insect native to North America and to which V. vinifera

roots have no natural resistance. Subsequently, rootstocks have been

developed based on other desirable characteristics including resistance

or tolerance to various nematodes (microscopic soil-borne roundworm)

and adaptation to different soil conditions. Rootstock variety may also

influence nutrient uptake, vigor of the scion variety (the

fruit-producing portion of a grafted vine) and to some extent its

phenology.

Most rootstocks are either native North American species or hybrids of two or more of these species, including Vitis riparia, Vitis berlandieri, and Vitis rupestris.

The rooting pattern and depth, as well as other root system

characteristics, vary among the species and hybrid rootstocks,

therefore the rootstock can influence aspects of vine growth, including

vigor, drought tolerance, nutrient uptake efficiency, and pest

resistance. Therefore, rootstock variety selection can be an important

factor in vineyard development.

The function of grapevine roots

° Provide a physical anchor of the vine

° Absorb water and mineral nutrients

° Store carbohydrates and nutrients in reserve for future use

° Produce hormones that control plant functions

The

root system of a mature grapevine consists of a woody framework of

older roots (Richards, 1983) from which permanent roots arise and grow

either horizontally or vertically. These roots are typically

multi-branching, producing lateral roots that can further branch into

smaller lateral roots. Lateral roots produce many short, fine roots,

which has the effect of increasing the area of soil exploited

(Richards, 1983). Certain soil fungi, called mycorrhizae, live in a

natural, mutually beneficial association with grape roots. Mycorrhizae

influence grapevine nutrition and growth, and have been shown to

increase the uptake of phosphorus.

The majority of the grapevine

root system is found within the top 3 feet (Richards, 1983; Winkler, et

al., 1974) of the soil, although individual roots can grow much deeper

in certain soil conditions and profiles. Distribution of roots is

influenced by soil characteristics: the presence of hardpans or other

impermeable layers, the rootstock variety, and cultural practices such

as the type of irrigation system (Mullins et al., 1992). Grapevine

roots require good internal soil drainage to function. Water-saturated

soils do not have air spaces that allow roots to respire. High water

tables and heavy textured soils (fine silty loams and clays) often

restrict root growth, and thereby limit vine size and nutrient uptake

from soils. Subsurface drainage tiles are often recommended in

non-irrigated production areas to improve internal soil drainage.

Reviewed by Tim Martinson, Cornell University and Patty Skinkis, Oregon State University

References:

Mullins, M. G., A. Bouquet, and L. E. Williams. 1992. Biology of the Grapevine. Cambridge University Press.

Richards, D. 1983. The Grape Root System. Horticultural Reviews 5:127-168.

Winkler,

A.J., J.A. Cook, W.M. Kliewer, and L.L. Lider. 1974. General

Viticulture. University of California Press. Berkeley, California.

Further Reading

Parts of the Grape Vine: Flowers and Fruit, eXtension Foundation

Parts of the Grape Vine: Shoots, eXtension Foundation

Grapevine Fruit Phenology, Aggie Horticulture® Texas A&M

AgriLife Extension pdf

Grapevine Shoot Phenology, Aggie Horticulture® Texas A&M

AgriLife Extension pdf

Grapevine Structure and Function, Oregon Viticulture pdf

Back to

Muscadine Grape Page

Bunch Grape Page

|