From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Soursop

Annona

muricata

ANNONACEAE

Of the 60 or more species of the genus Annona, family Annonaceae, the

soursop, A. muricata

L., is the most tropical, the largest-fruited, and the only one lending

itself well to preserving and processing.

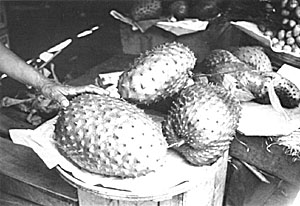

Plate 10: SOURSOP, Annona

muricata

It

is generally known in most Spanish-speaking countries as guanabana; in

E1 Salvador, as guanaba; in Guatemala, as huanaba; in Mexico, often as

zopote de viejas, or cabeza de negro; in Venezuela, as catoche or

catuche; in Argentina, as anona de puntitas or anona de broquel; in

Bolivia, sinini; in Brazil, araticum do grande, graviola, or jaca do

Para; in the Netherlands Antilles, sorsaka or zunrzak, the latter name

also used in Surinam andJava; in French-speaking areas of the West

Indies, West Africa, and Southeast Asia, especially North Vietnam, it

is known as corossol, grand corossol, corossol epineux, or cachiman

epineux. In Malaya it may be called durian belanda, durian maki; or

seri kaya belanda; in Thailand, thu-rian-khack.

In 1951, Prof.

Clery Salazar, who was encouraging the development of soursop products

at the College of Agriculture at Mayaguez, Puerto Rico, told me that

they would like to adopt an English name more appealing than the word

"soursop", and not as likely as guanabana to be mispronounced. To date,

no alternatives have been chosen.

Fig. 20: Exceptionally large and well-formed

soursops (Annona muricata)

in a Saigon market, 1968.

Description

The

soursop tree is low-branching and bushy but slender because of its

upturned limbs, and reaches a height of 25 or 30 ft (7.5-9 m). Young

branchlets are rusty-hairy. The malodorous leaves, normally evergreen,

are alternate, smooth, glossy, dark green on the upper surface, lighter

beneath; oblong, elliptic or narrow obovate, pointed at both ends, 2

1/2 to 8 in (6.25-20 cm) long and 1 to 2 1/2 in (2.5-6.25 cm) wide. The

flowers, which are borne singly, may emerge anywhere on the trunk,

branches or twigs. They are short stalked, 1 1/2 to 2 in (4 5 cm) long,

plump, and triangular-conical, the 3 fleshy, slightly spreading, outer

petals yellow-green, the 3 close-set inner petals pale-yellow.

The

fruit is more or less oval or heart-shaped, some times irregular,

lopsided or curved, due to improper carper development or insect

injury. The size ranges from 4 to 12 in (10-30 cm) long and up to 6 in

(15 cm) in width, and the weight may be up to 10 or 15 lbs (4.5-6.8

kg). The fruit is compound and covered with a reticulated,

leathery-appearing but tender, inedible, bitter skin from which

protrude few or many stubby, or more elongated and curved, soft,

pliable "spines". The tips break off easily when the fruit is fully

ripe. The skin is dark-green in the immature fruit, becoming slightly

yellowish-green before the mature fruit is soft to the touch. Its inner

surface is cream-colored and granular and separates easily from the

mass of snow-white, fibrous, juicy segments—much like flakes

of

raw fish—surrounding the central, soft-pithy core. In aroma,

the

pulp is somewhat pineapple-like, but its musky, subacid to acid flavor

is unique. Most of the closely-packed segments are seedless. In each

fertile segment there is a single oval, smooth, hard, black seed, l/2

to 3/4 in (1.25-2 cm) long; and a large fruit may contain from a few

dozen to 200 or more seeds.

Origin and

Distribution

Oviedo,

in 1526, described the soursop as abundant in the West Indies and in

northern South America. It is today found in Bermuda and the Bahamas,

and both wild and cultivated, from sea-level to an altitude of 3,500 ft

(1,150 m) throughout the West Indies and from southern Mexico to Peru

and Argentina. It was one of the first fruit trees carried from America

to the Old World Tropics where it has become widely distributed from

southeastern China to Australia and the warm lowlands of eastern and

western Africa. It is common in the markets of Malaya and southeast

Asia. Very large, symmetrical fruits have been seen on sale in South

Vietnam. It became well established at an early date in the Pacific

Islands. The tree has been raised successfully but has never fruited in

Israel.

In Florida, the soursop has been grown to a limited

extent for possibly 110 years. Sturtevant noted that it was not

included by Atwood among Florida fruits in 1867 but was listed by the

American Pomological Society in 1879. A tree fruited at the home of

John Fogarty of Manatee before the freeze of 1886. In the southeastern

part of the state and especially on the Florida Keys, it is often

planted in home gardens.

In regions where sweet fruits are

preferred, as in South India and Guam, the soursop has not enjoyed

great popularity. It is grown only to a limited extent in Madras.

However, in the East Indies it has been acclaimed one of the best local

fruits. In Honolulu, the fruit is occasionally sold but the demand

exceeds the supply. The soursop is one of the most abundant fruits in

the Dominican Republic and one of the most popular in Cuba, Puerto

Rico, the Bahamas, Colombia and northeastern Brazil.

In 1887,

Cuban soursops were selling in Key West, Florida, at 10 to 50 cents

apiece. In 1920, Wilson Popenoe wrote that: "In the large cities of

tropical America, there is a good demand for the fruits at all times of

the year, a demand which is not adequately met at present." The island

of Grenada produces particularly large and perfect soursops and

regularly delivers them by boat to the market of Port-of Spain because

of the shortage in Trinidad. In Colombia, where the soursop is

generally large, well-formed and of high quality, this is one of the 14

tropical fruits recommended by the Instituto Latinoamericano de

Mercadeo Agricola for large-scale planting and marketing. Soursops

produced in small plots, none over 5 acres (2.27 ha), throughout

Venezuela supply the processing plants where the frozen concentrate is

packed in 6 oz (170 g) cans. In 1968, 2,266 tons (936 MT) of juice were

processed in Venezuela. The strained pulp is also preserved

commercially in Costa Rica. There are a few commercial soursop

plantations near the south coast of Puerto Rico and several processing

factories. In 1977, the Puerto Rican crop totaled 219,538 lbs (99,790

kg).

At the First International Congress of Agricultural and

Food Industries of the Tropical and Subtropical Zones, held in 1964,

scientists from the Research Laboratories of Nestle Products in Vevey,

Switzerland, presented an evaluation of lesser-known tropical fruits

and cited the soursop, the guava and passionfruit as the 3 most

promising for the European market, because of their distinctive

aromatic qualities and their suitability for processing in the form of

preserved pulp, nectar and jelly.

Varieties

In

Puerto Rico, the wide range of forms and types of seedling soursops are

roughly divided into 3 general classifications: sweet, subacid, and

acid; then subdivided as round, heart-shaped, oblong or angular; and

finally classed according to flesh consistency which varies from soft

and juicy to firm and comparatively dry. The University of Puerto

Rico's Agricultural Experiment Station at one time cataloged 14

different types of soursops in an area between Aibonito and Coamo. In

El Salvador, 2 types of soursops are distinguished: guanaba azucaron

(sweet) eaten raw and used for drinks; and guanaba acida (very sour),

used only for drinks. In the Dominican Republic, the guanabana dulce

(sweet soursop) is most sought after. The term "sweet" is used in a

relative sense to indicate low acidity. A medium-sized, yellow-green

soursop called guanabana sin fibre (fiberless) has been vegetatively

propagated at the Agricultural Experiment Station at Santiago de las

Vegas, Cuba. The foliage of this superior clone is distinctly

bluish-green. In 1920, Dr. Wilson Popenoe sent to the United States

Department of Agriculture, from Costa Rica, budwood of a soursop he

named 'Bennett' in honor of G.S. Bennett, Agricultural Superintendent

of the Costa Rican Division of the United Fruit Company. He described

the fruit as large and handsome (as shown in the photograph

accompanying the introduction record No. 51050) and he declared the

tree to be the most productive he had seen.

Fig.

21: The soursop tree may bear fruits anywhere on its trunk or branches.

Multiple-stems of this tree are the result of its having been frozen to

the ground more than once.

Climate

The

soursop is truly tropical. Young trees in exposed places in southem

Florida are killed by only a few degrees of frost. The trees that

survive to fruiting age on the mainland are in protected situations,

close to the south side of a house and sometimes near a source of heat.

Even so, there will be temporary defoliation and interruption of

fruiting when the temperature drops to near freezing. In Key West,

where the tropical breadfruit thrives, the soursop is perfectly at

home. In Puerto Rico, the tree is said to prefer an altitude between

800 and 1,000 ft (244300 m), with moderate humidity, plenty of sun and

shelter from strong winds.

Soil

Best

growth is achieved in deep, rich, well-drained, semi-drysoil, but the

soursop tree can be and is commonly grown in acid and sandy soil, and

in the porous, oolitic limestone of South Florida and the Bahama

Islands.

Propagation

The

soursop is usually grown from seeds. They should be sown in flats or

containers and kept moist and shaded. Germination takes from 15 to 30

days. Selected types can be reproduced by cuttings or by

shield-budding. Soursop seedlings are generally the best stock for

propagation, though grafting onto custard apple (Annona reticulata),

the mountain soursop (A.

montana), or pond apple (A. glabra), is

usually successful. The pond apple has a dwarfing effect. Grafts on

sugar apple (A. squamosa)

and cherimoya (A.

cherimola) do not live for long, despite the fact that the

soursop is a satisfactory rootstock for sugar apple in Ceylon and India.

Culture

In

ordinary practice, seedlings, when 1 ft (30 cm) or more in height are

set out in the field at the beginning of the rainy season and spaced 12

to 15 ft (3.65-4.5 m) apart, though 25 ft (7.5 m) each way has been

suggested. A spacing of 20 x 25 ft (6x7.5 m) allows 87 trees per acre

(215/ha). Close-spacing, 8 x 8 ft (2.4x2.4 m) is thought aufficient for

small gardens in Puerto Rico. The tree grows rapidly and begins to bear

in 3 to 5 years. In Queensland, well-watered trees have attained 15 to

18 ft (4.5-5.5 m) in 6 to 7 years. Mulching is recommended to avoid

dehydration of the shallow, fibrous root system during dry, hot

weather. If in too dry a situation, the tree will cast off all of its

old leaves before new ones appear. A fertilizer mixture containing 10%

phosphoric acid, 10% potash and 3% nitrogen has been advocated in Cuba

and Queensland. But excellent results have been obtained in Hawaii with

quarterly applications of 10-10-10 N P K—½ lb (.225 kg) per

tree the first year, 1 lb (.45 kg)/tree the 2nd year, 3 lbs (1.36

kg)/tree the 3rd year and thereafter.

Season

The

soursop tends to flower and fruit more or less continuously, but in

every growing area there is a principal season of ripening. In Puerto

Rico, this is from March to June or September; in Queensland, it begins

in April; in southern India, Mexico and Florida, it extends from June

to September; in the Bahamas, it continues through October. In Hawaii,

the early crop occurs from January to April; midseason crop, June to

August, with peak in July; and there is a late crop in October or

November.

Harvesting

The

fruit is picked when full grown and still firm but slightly

yellow-green. If allowed to soften on the tree, it will fall and crush.

It is easily bruised and punctured and must be handled with care. Firm

fruits are held a few days at room temperature. When eating ripe, they

are soft enough to yield to the slight pressure of one's thumb. Having

reached this stage, the fruit can be held 2 or 3 days longer in a

refrigerator. The skin will blacken and become unsightly while the

flesh is still unspoiled and usable. Studies of the ripening process in

Hawaii have determined that the optimum stage for eating is 5 to 6 days

after harvest, at the peak of ethylene production. Thereafter, the

flavor is less pronounced and a faint off odor develops. In Venezuela,

the chief handicap in commercial processing is that the fruits stored

on racks in a cool shed must be gone over every day to select those

that are ripe and ready for juice extraction.

Yield

The

soursop, unfortunately, is a shy-bearer, the usual crop being 12 to 20

or 24 fruits per tree. In Puerto Rico, production of 5,000 to 8,000 lbs

per acre (roughly equal kg/ha), is considered a good yield from

well-cared-for trees. A study of the first crop of 35 5 year-old trees

in Hawaii showed an average of 93.6 lbs (42.5 kg) of fruits per tree.

Yield was slightly lower the 2nd year. The 3rd year, the average yield

was 172 lbs (78 kg) per tree. At this rate, the annual crop would be

16,000 lbs per acre (roughly equal kg/ha).

Pests

& Diseases

Queensland's

principal soursop pest is the mealybug which may occur in masses on the

fruits. The mealybug is a common pest also in Florida, where the tree

is often infested with scale insects. Sometimes it may be infected by a

lace-wing bug.

The fruit is subject to attack by fruit flies—Anastrepha suspensa,

A. striata

and Ceratitis capitata.

Red spiders are a problem in dry climates.

Dominguez

Gil (1978 and 1983), presents an extensive list of pests of the soursop

in the State of Zulia, Venezuela. The 5 most damaging are: 1) the wasp,

Bephratelloides (Bephrata)

maculicollis,

the larvae of which live in the seeds and emerge from the fully-grown

ripe fruit, leaving it perforated and highly perishable; 2) the moth, Cerconota (Stenoma) anonella,

which lays its eggs in the very young fruit causing stunting and

malformation; 3) Corythucha

gossipii; which attacks the leaves; 4) Cratosomus inaequalis,

which bores into the fruit, branches and trunk; 5) Laspeyresia sp.,

which perforates the flowers. The first 3 are among the 7 major pests

of the soursop in Colombia, the other 4 being: Toxoptera aurantii;

which affects shoots, young leaves, flowers and fruits; present but not

important in Venezuela; Aphis

spiraecola; Empoasca

sp., attacking the leaves; and Aconophora

concolor, damaging the flowers and fruits. Important

beneficial agents preying on aphids are Aphidius testataceipes,

Chrysopa

sp., and Curinus

sp. Lesser enemies of the soursop in South America include: Talponia backeri

and T. batesi

which damage flowers and fruits; Horiola

picta and H.

lineolata, feeding on flowers and young branches; Membracis foliata,

attacking young branches, flower stalks and fruits; Saissetia nigra; Escama ovalada, on

branches, flowers and fruits; Cratosomus

bombina, a fruit borer; and Cyclocephala signata,

affecting the flowers.

In Trinidad, the damage done to soursop flowers by Thecla ortygnus

seriously limits the cultivation of this fruit. The sphinx caterpillar,

Cocytius

antueus may be found feeding on soursop leaves in

Puerto Rico. Bagging of soursops is necessary to protect them from Cerconota anonella.

However, one grower in the Magdalena Valley of Colombia claims that

bagged fruits are more acid than others and the flowers have to be

handpollinated.

It has been observed in Venezuela and El

Salvador that soursop trees in very humid areas often grow well but

bear only a few fruits, usually of poor quality, which are apt to rot

at the tip. Most of their flowers and young fruits fall because of

anthracnose caused by Collectotrichum

gloeosporioides.

It has been said that soursop trees for cultivation near San Juan,

Puerto Rico, should be seedlings of trees from similarly humid areas

which have greater resistance to anthracnose than seedlings from dry

zones. The same fungus causes damping-off of seedlings and die-back of

twigs and branches.

Occasionally the fungus, Scolecotrichum

sp. ruins the leaves in Venezuela. In the East Indies, soursop trees

are sometimes subject to the root-fungi, Fomes lamaoensis

and Diplodia

sp. and by pink disease due to Corticum

salmonicolor.

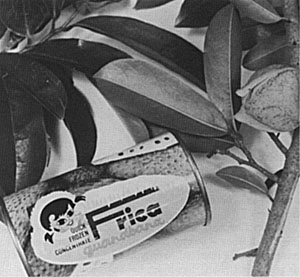

Fig. 22: Canned soursop concentrate is produced in Venezuela. On the

branch at the right is a soursop flower.

Food Uses

Soursops

of least acid flavor and least fibrous consistency are cut in sections

and the flesh eaten with a spoon. The seeded pulp may be torn or cut

into bits and added to fruit cups or salads, or chilled and served as

dessert with sugar and a little milk or cream. For years, seeded

soursop has been canned in Mexico and served in Mexican restaurants in

New York and other northern cities.

Most widespread throughout

the tropics is the making of refreshing soursop drinks (called champola

in Brazil; carato in Puerto Rico). For this purpose, the seeded pulp

may be pressed in a colander or sieve or squeezed in cheesecloth to

extract the rich, creamy juice, which is then beaten with milk or water

and sweetened. Or the seeded pulp may be blended with an equal amount

of boiling water and then strained and sweetened. If an electric

blender is to be used, one must first be careful to remove all the

seeds, since they are somewhat toxic and none should be accidentally

ground up in the juice.

In Puerto Rican processing factories,

the hand-peeled and cored fruits are passed through a mechanical pulper

having nylon brushes that press the pulp through a screen, separating

it from the seeds and fiber. A soursop soft drink, containing 12 to 15%

pulp, is canned in Puerto Rico and keeps well for a year or more. The

juice is prepared as a carbonated bottled beverage in Guatemala, and a

fermented, cider-like drink is sometimes made in the West Indies. The

vacuum-concentrated juice is canned commercially in the Philippines.

There soursop drinks are popular but the normal "milk" color is not.

The people usually add pink or green food coloring to make the drinks

more attractive. The strained pulp is said to be a delicacy mixed with

wine or brandy and seasoned with nutmeg. Soursop juice, thickened with

a little gelatin, makes an agreeable dessert.

In the Dominican

Republic, a soursop custard is enjoyed and a confection is made by

cooking soursop pulp in sugar sirup with cinnamon and lemon peel.

Soursop ice cream is commonly frozen in refrigerator ice-cube trays in

warm countries.

In the Bahamas, it is simply made by mashing the

pulp in water, letting it stand, then straining to remove fibrous

material and seeds. The liquid is then blended with sweetened condensed

milk, poured into the trays and stirred several times while freezing. A

richer product is made by the usual method of preparing an ice cream

mix and adding strained soursop pulp just before freezing. Some Key

West restaurants have always served soursop ice cream and now the

influx of residents from the Caribbean and Latin American countries has

created a strong demand for it. The canned pulp is imported from

Central America and Puerto Rico and used in making ice cream and

sherbet commercially. The pulp is used, too, for making tarts and

jelly, sirup and nectar. The sirup has been bottled in Puerto Rico for

local use and export. The nectar is canned in Colombia and frozen in

Puerto Rico and is prepared fresh and sold in paper cartons in the

Netherlands Antilles. The strained, frozen pulp is sold in plastic bags

in Philippine supermarkets.

Immature soursops are cooked as

vegetables or used in soup in Indonesia. They are roasted or fried in

northeastern Brazil. I have boiled the half-grown fruit whole, without

peeling. In an hour, the fruit is tender, its flesh off-white and

mealy, with the aroma and flavor of roasted ears of green corn (maize).

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Calories |

61.3-53.1 |

| Moisture |

82.8g |

| Protein |

1.00g |

| Fat |

0.97g |

| Carbohydrates |

14.63g |

| Fiber |

0.79g |

| Ash |

60g |

| Calcium |

10.3

mg |

| Phosphorus |

27.7

mg |

| Iron |

0.64

mg |

| Vitamin

A (B-carotene) |

0 |

| Thiamine

|

0.11

mg |

| Riboflavin |

0.05

mg |

| Niacin |

1.28mg |

| Ascorbic

Acid |

29.6

mg |

Amino

Acids: |

|

| Tryptophan |

11

mg |

| Methionine |

7

mg |

| Lysine |

60mg |

*Analyses made at the Laboratorio FIM de Nutricion, Havana, Cuba. |

|

Toxicity

The

presence of the alkaloids anonaine and anoniine has been reported in

this species. The alkaloids muricine, C19H21O4N (possibly

des-N-methylisocorydine or des-N methylcorydine) and muricinine,

C18H19O4 (possibly des-N-methylcorytuberine), are found in the bark.

Muricinine is believed to be identical to reticuline. An unnamed

alkaloid occurs in the leaves and seeds. The bark is high in

hydrocyanic acid. Only small amounts are found in the leaves and roots

and a trace in the fruit. The seeds contain 45% of a yellow non-drying

oil which is an irritant poison, causing severe eye inflamation.

Other Uses

Fruit:

In the Virgin Islands, the fruit is placed as a bait in fish

traps.

Seeds:

When pulverized, the seeds are effective pesticides against head lice,

southern army worms and pea aphids and petroleum ether and chloroform

extracts are toxic to black carpet beetle larvae. The seed oil kills

head lice.

Leaves:

The leaf decoction is lethal to head lice and bedbugs.

Bark:

The bark of the tree has been used in tanning. The bark fiber is strong

but, since fruiting trees are not expendable, is resorted to only in

necessity. Bark, as well as seeds and roots, has been used as fish

poison.

Wood:

The wood is pale, aromatic, soft, light in weight

and not durable. It has been used for ox yokes because it does not

cause hair loss on the neck.

In Colombia, it is deemed to be

suitable for pipestems and barrel staves. Analyses in Brazil show

cellulose content of 65 to 76%, high enough to be a potential source of

paper pulp.

Medicinal Uses:

The juice of the ripe fruit is said

to be diuretic and a remedy for haematuria and urethritis. Taken when

fasting, it is believed to relieve liver ailments and leprosy.

Pulverized immature fruits, which are very astringent, are decocted as

a dysentery remedy. To draw out chiggers and speed healing, the flesh

of an acid soursop is applied as a poultice unchanged for 3 days.

In

Materia Medica of British Guiana, we are told to break soursop leaves

in water, "squeeze a couple of limes therein, get a drunken man and rub

his head well with the leaves and water and give him a little of the

water to drink and he gets as sober as a judge in no time." This

sobering or tranquilizing formula may not have been widely tested, but

soursop leaves are regarded throughout the West Indies as having

sedative or soporific properties. In the Netherlands Antilles, the

leaves are put into one's pillowslip or strewn on the bed to promote a

good night's sleep. An infusion of the leaves is commonly taken

internally for the same purpose. It is taken as an analgesic and

antispasmodic in Esmeraldas Province, Ecuador. In Africa, it is given

to children with fever and they are also bathed lightly with it. A

decoction of the young shoots or leaves is regarded in the West Indies

as a remedy for gall bladder trouble, as well as coughs, catarrh,

diarrhea, dysentery and indigestion; is said to "cool the blood," and

to be able to stop vomiting and aid delivery in childbirth. The

decoction is also employed in wet compresses on inflammations and

swollen feet. The chewed leaves, mixed with saliva, are applied to

incisions after surgery, causing proud flesh to disappear without

leaving a scar. Mashed leaves are used as a poultice to alleviate

eczema and other skin afflictions and rheumatism, and the sap of young

leaves is put on skin eruptions.

The roots of the tree are

employed as a vermifuge and the root bark as an antidote for poisoning.

A tincture of the powdered seeds and bay rum is a strong emetic.

Soursop flowers are believed to alleviate catarrh.

|

|