From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Banana

Musa x paridasiaca

MUSACEAE

The word "banana" is a general term embracing a number of species or

hybrids in the genus Musa

of the family Musaceae. Some species such as M. Basjoo Sieb.

& Zucc. of Japan and M.

ornata Roxb., native from Pakistan to Burma, are grown

only as ornamental plants or for fiber. M. textilis Nee of

the Philippines is grown only for its fiber, prized for strong ropes

and also for tissue-thin tea bags. The so-called Abyssinian banana, Ensete ventricosum

Cheesman, formerly E.

edule Horan, Musa

ensete Gmel., is cultivated in Ethiopia

for fiber and for the staple foods derived from the young shoot, the

base of the stem, and the corm.

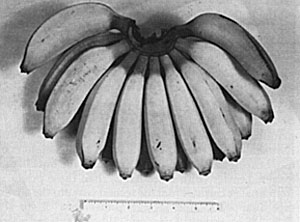

Plate III: DWARF CAVENDISH BANANA, Musa

acuminata

Most edible-fruited bananas, usually seedless, belong to the species M. acuminata Colla (M. cavendishii

Lamb. ex Paxt., M.

chinensis Sweet, M.

nana Auth. NOT

Lour., M. zebrina

Van Houtee ex Planch.), or to the hybrid M. X paradisiaca L. (M. X sapientum L.; M. acumianta X M. balbisiana

Colla).

M. balbisiana

Colla of southern Asia and the East Indies, bears a seedy fruit but the

plant is valued for its disease-resistance and therefore plays an

important role as a "parent"; in the breeding of edible bananas.

M. fehi

Bertero ex Vieill. and M.

troglodytarum L. have been applied to the group of bananas

known as fehi or fe'i but taxonomists have yet to make final decisions

as to the applicability of these binomials.

To the American consumer "banana" seems a simple name for the yellow

fruits so abundantly marketed for consumption raw and "plantain" for

the larger, more angular fruits intended for cooking but also edible

raw when fully ripe. However, the distinction is not that clear and the

terms may even be reversed. The types we call "banana" are known by

similar or very different names in banana-growing areas.

Spanish-speaking people say banana china (Paraguay), banano enano

(Costa Rica), cambur or camburi (Colombia, Venezuela), cachaco,

colicero, cuatrofilos (Colombia); carapi (Paraguay), curro (Panama),

guineo (Costa Rico, Puerto Rico, E1 Salvador); murrapo (Colombia);

mampurro (Dominican Republic); patriota (Panama); platano (Mexico);

platano de seda (Peru); platano enano (Cuba); suspiro (Dominican

Republic); zambo (Honduras). Portuguese names in Brazil are: banana

maca, banana de Sao Tome', banana da Prata. In French islands or areas,

the terms may be bananier nain, bananier de Chine (Guadaloupe), figue,

figue banane, figue naine (Haiti). Where German is spoken, they say:

echte banane, feige, or feigenbaum. In the Sudan, baranda.

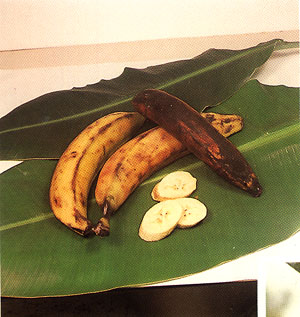

The types Americans call "plantain" Plate IV, may be known as banaan

(Surinam); banano macho (Panama); banane or bananier (Haiti,

Guadeloupe, Martinique); banane misquette or banane musquee, or pie

banane (Haiti); bananeira de terra (Brazil); banano indio (Costa Rica);

barbaro (Mexico); butuco (Honduras); parichao (Venezuela); plantain

(Guyana, Jamaica, Trinidad); platano (Cuba, Puerto Rico, Dominican

Republic); platano burro, platano hembra (Cuba); platano macho (Cuba,

Panama); platano de la isla (Peru); topocho or yapuru (Venezuela);

zapolote (Mexico). Numerous other vernacular names, according to

geographical region, are provided by N.W. Simmonds in his textbook,

Bananas.

In India, there is no distinction between bananas and plantains. All

cultivars are merely rated as to whether they are best for dessert or

for cooking.

Plate IV: PLANTAIN, Musa

× paradisiaca

Description

The banana plant, often erroneously referred to as a "tree", is a large

herb, with succulent, very juicy stem (properly "pseudostem") which is

a cylinder of leaf-petiole sheaths, reaching a height of 20 to 25 ft

(6-7.5 m) and arising from a fleshy rhizome or corm. Suckers spring up

around the main plant forming a clump or "stool'', the eldest sucker

replacing the main plant when it fruits and dies, and this process of

succession continues indefinitely. Tender, smooth, oblong or elliptic,

fleshy-stalked leaves, numbering 4 or 5 to 15, are arranged spirally.

They unfurl, as the plant grows, at the rate of one per week in warm

weather, and extend upward and outward, becoming as much as 9 ft (2.75

m) long and 2 ft (60 cm) wide. They may be entirely green, green with

maroon splotches, or green on the upperside and red purple beneath. The

inflorescence, a transformed growing point, is a terminal spike

shooting out from the heart in the tip of the stem. At first, it is a

large, long-oval, tapering, purple-clad bud. As it opens, it is seen

that the slim, nectar-rich, tubular, toothed, white flowers are

clustered in whorled double rows along the floral stalk, each cluster

covered by a thick, waxy, hoodlike bract, purple outside, deep-red

within. Normally, the bract will lift from the first hand in 3 to 10

days. If the plant is weak, opening may not occur until 10 or 15 days.

Female flowers occupy the lower 5 to 15 rows; above them may be some

rows of hermaphrodite or neuter flowers; male flowers are borne in the

upper rows. In some types the inflorescence remains erect but

generally, shortly after opening, it begins to bend downward. In about

one day after the opening of the flower clusters, the male flowers and

their bracts are shed, leaving most of the upper stalk naked except at

the very tip where there usually remains an unopened bud containing the

last-formed of the male flowers. However, there are some mutants such

as 'Dwarf Cavendish' with persistent male flowers and bracts which

wither and remain, filling the space between the fruits and the

terminal bud.

As the young fruits develop from the female flowers, they look like

slender green fingers. The bracts are soon shed and the fully grown

fruits in each cluster become a "hand" of bananas, and the stalk droops

with the weight until the bunch is upside down. The number of "hands"

varies with the species and variety.

The fruit (technically a "berry") turns from deep-green to yellow or

red, or, in some forms, green-and white-striped, and may range from 2

1/2 to 12 in (6.4-30 cm) in length and 3/4 to 2 in (1.9-5 cm) in width,

and from oblong, cylindrical and blunt to pronouncedly 3-angled,

somewhat curved and hornlike. The flesh, ivory-white to yellow or

salmon-yellow, may be firm, astringent, even gummy with latex, when

unripe, turning tender and slippery, or soft and mellow or rather dry

and mealy or starchy when ripe. The flavor may be mild and sweet or

subacid with a distinct apple tone. Wild types may be nearly filled

with black, hard, rounded or angled seeds 1/8 to 5/8 in (3-16 mm) wide

and have scant flesh. The common cultivated types are generally

seedless with just minute vestiges of ovules visible as brown specks in

the slightly hollow or faintly pithy center, especially when the fruit

is overripe. Occasionally, cross-pollination by wild types will result

in a number of seeds in a normally seedless variety such as 'Gros

Michel', but never in the Cavendish type.

Origin and

Distribution

Edible bananas originated in the Indo-Malaysian region reaching to

northern Australia. They were known only by hearsay in the

Mediterranean region in the 3rd Century B.C., and are believed to have

been first carried to Europe in the 10th Century A.D. Early in the 16th

Century, Portuguese mariners transported the plant from the West

African coast to South America. The types found in cultivation in the

Pacific have been traced to eastern Indonesia from where they spread to

the Marquesas and by stages to Hawaii.

Bananas and plantains are today grown in every humid tropical region

and constitute the 4th largest fruit crop of the world, following the

grape, citrus fruits and the apple. World production is estimated to be

28 million tons—65% from Latin America, 27 % from Southeast

Asia, and 7 % from Africa. One-fifth of the crop is exported to Europe,

Canada, the United States and Japan as fresh fruit. India is the

leading banana producer in Asia. The crop from 400,000 acres (161,878

ha) is entirely for domestic consumption. Indonesia produces over 2

million tons annually, the Philippines about 1/2 million tons,

exporting mostly to Japan. Taiwan raises over 1/2 million tons for

export. Tropical Africa (principally the Ivory Coast and Somalia) grows

nearly 9 million tons of bananas each year and exports large quantities

to Europe.

Brazil is the leading banana grower in South America—about 3

million tons per year, mostly locally consumed, while Colombia and

Ecuador are the leading exporters. Venezuela's crop in 1980 reached

983,000 tons. Large scale commercial production for export to North

America is concentrated in Honduras (where banana fields may cover 60

sq mi) and Panama, and, to a lesser extent, Costa Rica. In the West

Indies, the Windward Islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe are the main

growers and for many years have regularly exported to Europe. Green

bananas are the basic food of the people of Western Samoa and large

quantities are exported.

In Ghana, the plantain is a staple food but up to the late 1960's the

crop was grown only in home gardens or as a shade for cacao. When the

cacao trees declined, solid plantings of plantain were established in

their place and in newly cleared forest land where the richness of

organic matter greatly promotes growth. By 1977, Ghana was harvesting

2,204,000 tons (2,000,000 MT) annually.

The plantain is the most important starchy food of Puerto Rico and is

third in monetary value among agricultural crops, being valued at

$30,000,000 annually. While improved methods of culture have been

adopted in recent years and production has been increased by 15% in

1980, it was still necessary to import 1,328 tons (1,207 MT) to meet

local demand. Annual per capita consumption is said to be 65 lbs (29.5

kg). In the past, most of the plantains in Puerto Rico were grown on

humid mountainsides. High prices have induced some farmers to develop

plantations on level irrigated land formerly devoted to sugarcane.

In tropical zones of Colombia, plantains are not only an important part

of the human diet but the fruits and the plants furnish indispensable

feed for domestic animals as well. The total plantain area is about

1,037,820 acres (420,000 ha) with a yield of 5,500 lbs per acre (5,500)

kg/ha). Mexico grows about 1/6 as much, 35% under irrigation, and the

crop is valued at $1,335 US per acre ($3,300 US/ha). Venezuela has

somewhat less of a crop 517,000 tons from 146,000 acres (59,000 ha) in

1980—and the Dominican Republic is fourth in order with about

114,600 acres (46,200 ha). Bananas and plantains are casually grown in

some home gardens in southern Florida. There are a few small commercial

plantations furnishing local markets.

Varieties

Edible bananas are classified into several main groups and subgroups.

Simmonds placed first the diploid M. acuminata group 'Sucrier',

represented in Malaya, Indonesia, the Philippines, southern India, East

Africa, Burma, Thailand, the West Indies, Colombia and Brazil. The

sheaths are dark-brown, the leaves yellowish and nearly free of wax.

The bunches are small and the fruits small, thin-skinned and sweet.

Cultivars of this group are more important in New Guinea than elsewhere.

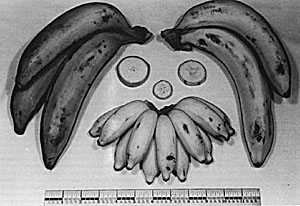

Fig.

8: Green plantains (left), 'Gros Michel' bananas(right) and 'Lady

Finger' (center). In: K. and J. Morton, Fifty Tropical Fruits of

Nassau, 1946.

Here belongs one of the smallest of the well-known bananas, the 'Lady

Finger', also known as'Date' or 'Fig', and, in Spanish, as 'Dedo de

Dama', 'Datil', 'Nino', Bocadillo', 'Manices', 'Guineo Blanco', or

'Cambur Titiaro'. The plant reaches 25 ft (7.5 m) in height, has a

slender trunk but a heavy root system that fortifies the plant against

strong winds. The outer sheaths have streaks or patches of reddish

brown. The bunch consists of 10 to 14 hands each of 12 to 20 fingers.

The fruit is 4 to 5 in (10-12.5 cm) long, with thin, light-yellow skin

and sweet flesh. This cultivar is resistant to drought, Panama disease

and the black weevil but subject to Sigatoka (leaf spot). It is common

in Latin America and commercial in Queensland and New South Wales.

In second place, there is the group represented by the prominent and

widely cultivated 'Gros Michel' originally from Burma, Thailand,

Malaya, Indonesia and Ceylon. It was introduced into Martinique early

in the 19th Century by a French naval officer and, a few years later,

was taken to Jamaica; from there it was carried to Fiji, Nicaragua,

Hawaii and Australia, in that sequence. It is a large, tall plant

bearing long bunches of large, yellow fruits, and it was formerly the

leading commercial cultivar in Central Africa, Latin America and the

Caribbean, but has been phased out because of its great susceptibility

to Panama disease. It has given rise to several named sports or mutants.

The Cavendish subgroup includes several

important bananas:

a) The 'Dwarf Cavendish',

Plate III, first known from China and widely

cultivated, especially in the Canary Islands, East Africa and South

Africa. The plant is from 4 to 7 ft (1.2-2.1 m) tall, with broad leaves

on short petioles. It is hardy and wind resistant. The fruit is of

medium size, of good quality, but thin-skinned and must be handled and

shipped with care. This cultivar is easily recognized because the male

bracts and flowers are not shed.

b) The 'Giant Cavendish',

also known as 'Mons Mari, 'Williams',

'Williams Hybrid', or 'Grand Naine', is of uncertain origin, closely

resembles the 'Gros Michel', and has replaced the 'Dwarf' in Colombia,

Australia, Martinique, in many Hawaiian plantations, and to some extent

in Ecuador. It is the commercial banana of Taiwan. The plant reaches 10

to 16 ft (2.7-4.9 m). The pseudostem is splashed with darkbrown, the

bunch is long and cylindrical, and the fruits are larger than those of

the 'Dwarf' and not as delicate. Male bracts and flowers are shed,

leaving a space between the fruits and the terminal bud.

c) 'Pisang masak hijau',

or 'Bungulan', the triploid Cavendish clone of

the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaya, is erroneously called 'Lacatan'

in Jamaica where it replaced 'Gros Michel' because of its immunity to

Panama disease, though it is subject to Sigatoka (leaf spot). The plant

is tall and slender and prone to wind injury. Its fruits ripen unevenly

in winter, bruise easily and are inclined to spoil in storage. It is no

longer grown commercially in Jamaica and the Windward Islands. The

fruits are commonly used as cooking bananas in Jamaican households.

Simmonds declares this cultivar is not the true 'Lacatan' of the

Philippines. He suggested that 'Pisang masak hijau' may have been the

primary source of all the members of the Cavendish group.

d) 'Robusta',

very similar to the so-called 'Lacatan', has largely

replaced that cultivar in Jamaica and the Windward Islands and the

'Gros Michel' in Central America because it is shorter, thick-stemmed,

less subject to wind. It is being grown commercially also in Brazil,

eastern Australia, Samoa and Fiji. It is resistant to Panama disease

but prone to Sigatoka.

e) 'Valery',

also a triploid Cavendish clone, closely resembles

'Robusta' and some believe it may be the same. However, it is being

grown as a successor to 'Robusta'. It is already more widely cultivated

than 'Lacatan' for export. As compared with other clones in cooking

trials, it has low ratings because cooking hardens the flesh and gives

it a waxy texture.

Fig. 9: 'Radja' banana, introduced

into Florida by Dr. J.J. Ochse about 1957.

The Banana Breeding Research Scheme in Jamaica has developed a number

of tetraploid banana clones with superior disease-resistance and some

are equal in dessert quality to the so-called 'Lacatan' and 'Valery'.

'Bluggoe'

(with many other local names) is a cooking banana especially

resistant to Panama disease and Sigatoka. It bears a few distinctly

separated hands of large, almost straight, starchy fruits, and is of

great importance in Burma, Thailand, southern India, East Africa, the

Philippines, Samoa, and Grenada.

'Ice Cream'

banana of Hawaii ('Cenizo' of Central America and the West

Indies; 'Krie' of the Philippines), is a relative of 'Bluggoe'. The

plant grows to 10 or 15 ft (3-4.5 m), the leaf midrib is light pink,

the flower stalk may be several feet long, but the bunch has only 7 to

9 hands. The fruit is 7 to 9 in (17.5 22.8 cm) long, up to 2 1/2 in

(6.25 cm) thick, 4-to 5-angled, bluish with a silvery bloom when young,

pale yellow when ripe, The flesh is white, sweetish, and is eaten raw

or cooked.

'Mysore',

also known as 'Fillbasket' and 'Poovan', is the most

important banana type of India, constituting 70% of the total crop. It

is sparingly grown in Malaya, Thailand, Ceylon and Burma. It is thought

to have been introduced into Dominice in 1900 but the only place where

it is of any importance in the New World is Trinidad where it is

cultivated as shade for cacao. The plant is large and vigorous, immune

to Panama disease and nearly so to Sigatoka; very hardy and drought

tolerant. It bears large, compact bunches of medium sized, plump, thin

skinned, attractive, bright yellow fruits of subacid flavor.

Other prominent commercial cultivars are 'Salembale' and 'Rasabale',

not suitable for canning because of starchy taste and weak flavor.

'Pachabale' and 'Chandrabale' are important local varieties preferred

for canning. K.C. Naik described 34 cultivars as the more important

among the many grown in South India.

'Silk',

'Silk Fig', or 'Apple' ('Manzana' in Spanish), is the most

popular dessert banana of the tropics. It is widely distributed around

the tropics and subtropics but never grown on a large scale. The plant

is 10 to 12 ft (3-3.6m) tall, only medium in vigor, very resistant to

Sigatoka but prone to Panama disease. There are only 6 to 12 hands in

the bunch, each with 16 to 18 fruits. The plump bananas are 4 to 6 in

(10-15 cm) long, slightly curved; astringent when unripe but pleasantly

subacid when fully ripe; and apple scented. If left on the bunch until

fully developed, the thin skin splits lengthwise and breaks at the stem

end causing the fruit to fall, but it is firm and keeps well on hand in

the home.

The 'Red',

'Red Spanish', 'Red Cuban', 'Colorado', or 'Lal Kela' banana

may have originated in India, where it is frequently grown, and it has

been introduced into all banana growing regions. The plant is large,

takes 18 months from planting to harvest. It is highly resistant to

disease. The pseudostem, petiole, midrib and fruit peel are all

purplish red, but the latter turns to orange yellow when the fruit is

fully ripe. The bunch is compact, may contain over 100 fruits of medium

size, with thick peel, and flesh of strong flavor. In the mutant called

'Green Red', the plant is variegated green and red, becomes 28 ft (8.5

m) tall with pseudostem to 18 in (45 cm) thick at the base. The bunch

bears 4 to 7 hands, the fruits are thick, 5 to 7 in (12.5 17.5 cm)

long. The purplish-red peel changes to orange-yellow and the flesh is

firm, cream-colored and of good quality.

The 'Fehi'

or 'Fe'i' group, of Polynesia, is distinguished by the erect

bunches and the purplish-red or reddish-yellow sap of the plants which

has been used as ink and for dyeing. The plants may reach 36 ft (10.9

m) and the leaves are 20 to 30 in (50-75 cm) wide. The bunches have

about 6 hands of orange or copper-colored, thick skinned fruits which

are starchy, sometimes seedy, of good flavor when boiled or roasted.

These plants are often grown as ornamentals in Hawaii.

As a separate group, Simmonds places the 'I.C. 2', or 'Golden Beauty'

banana especially bred at the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture

in Trinidad in 1928 by crossing the 'Gros Michel' with a wild Musa

acuminata. It is resistant to Panama disease and very resistant to

Sigatoka. Though the bunches are small and the fruits short, they ship

and ripen well and this cultivar is grown for export in Honduras and

has been planted in Hawaii, Samoa and Fiji.

'Orinoco',

'Horse', 'Hog', or 'Burro', banana, a medium tall, sturdy

plant, is particularly hardy. The bunch consists of only a few hands of

very thick, 3 angled fruits about 6 in (15 cm) long. The flesh has a

salmon tint, is firm, edible raw when fully ripe but much better cooked

fried, baked or otherwise, as are plantains.

Trials of 5 clones of 'Giant Cavendish' and 9 other cultivars ('Robusta

A', 'Robusta B', 'Cocos A', 'Cocos B', 'Golden Beauty', 'Enano Nautia',

'Enano Gigante', 'Enano' and 'Valery') were made between 1976 and 1979

at the Campo Agricola Experimental at Tecoman, Mexico. 'Enano Gigante'

is the most widely grown cultivar in that region but the tests showed

that 'Enano Nautia' and 'Golden Beauty' bore heavier bunches of better

quality fruit, even though 'Enano Gigante' had a greater number of

bunches and highest yield per ground area. 'Giant Cavendish' clones 1,

2, 3 and 4, and 'Cocos B' grew very tall, gave low yields and the fruit

was of poor quality.

Among the plantains, there are many forms, some with pink, red or

dark-brown leaf sheaths, some having also colored midribs or splotches

on leaves or fruits. The plants are usually large, vigorous and

resistant to Panama disease and Sigatoka but attacked by borers. Major

subgroups are known as 'French plantain' and 'Horn plantain', the

former with persistent male flowers. The usually large, angled fruits

are borne in few hands. All are important sources of food in southern

India, East Africa, tropical America and the West Indies. The tall

'Maricongo' and the 'Common Dwarf' are leading commercial cultivars. A

dwarf mutant is the 'Plantano enano of Puerto Rico ('banane cochon' of

Haiti). Ordinary plantains are called 'cuadrado', 'chato', and

'topocho' in Mexico. The leading commercial cultivars are 'Pelipita'

and 'Saba' which are resistant to Black Sigatoka but they do not have

the high culinary quality of 'Harton', 'Dominico-Harton', 'Currare',

and 'Horn'. 'Laknau' is a fertile plantain that resembles 'Horn' but is

of inferior quality. It has opened up possibilities for hybridizing and

is being crossed with 'Pelipita' and 'Saba'.

Banana and plantain cultivars most often grown in Florida are the

'Dwarf Cavendish', 'Apple', and 'Orinoco' bananas and the 'Macho'

plantain. The 'Red' and 'Lady Finger' bananas are very occasionally

grown in sheltered locations.

There are five major collections of banana and plantain clones in the

world. United Brands maintains a collection of 470 cultivars and 100

species at La Lima, Honduras.

Climate

The edible bananas are restricted to tropical or neartropical regions,

roughly the area between latitudes 30°N and 30°S.

Within this band, there are varied climates with different lengths of

dry season and different degrees and patterns of precipitation. A

suitable banana climate is a mean temperature of 80°F

(26.67°C) and mean rainfall of 4 in (10 cm) per month. There

should not be more than 3 months of dry season.

Cool weather and prolonged drought retard growth. Banana plants produce

only one leaf per month in winter, 4 per month in summer. If low

temperatures occur just at flowering time, the bud may not be able to

emerge from the stem. If fruits have already formed, maturity may be

delayed several months or completely suspended. If only the leaves are

destroyed, the fruits will be exposed to sunburn. Smudging, by burning

dry trash covered with green clippings to create smoke, can raise the

temperature 2 to 4 degrees. Flooding the field in advance of a cold

snap will keep the ground warm if the chill weather is brief. In

Australia, bananas are planted on sunny hill sides at elevations of 200

to 1,000 ft (60 to 300 m) to avoid the cold air that settles at lower

levels. Brief frosts kill the plants to the ground but do not destroy

the corm. 'Dwarf Cavendish' and the 'Red' banana are particularly

sensitive to cold, whereas the dwarf cultivar 'Walha', or 'Kullen', of

India is successful up to 4,000 ft (1,220 m) in the outer range of the

Western Ghats. 'Vella vazhai' is extensively cultivated in the Lower

Pulneys between 3,200 and 5,500 ft (975 and 1,616 m). A cooking banana,

'Plankel', survives winters in home gardens in northern India. In South

Africa, the main banana-producing area is along the southeast coast at

3,000 ft (915 m) above sea level with summer rainfall of 35 to 45 in

(90-115 cm). The major part of the crop in East Africa is grown between

4,000 and 5,000 ft (1,220 and 1,524 m) and the total range extends from

sea-level to 7,500 ft (2,286 m).

Wind

is detrimental to banana plants. Light winds shred the leaves,

interfering with metabolism; stronger winds may twist and distort the

crown. Winds to 30 mph break the petioles; winds to 40 mph will topple

a pseudostem that is supporting the weight of a heavy bunch unless the

stem is propped, and may cause root damage in non fruiting plants that

are not blown down; winds of 60 mph or over will uproot entire

plantations, especially when the soil is saturated by rain. Windbreaks

are often planted around banana fields to provide some protection from

cold and wind. Cyclones and hurricanes are devastating and the latter

were the main reason for the shift of large scale banana production

from the West Indies to Central America, Colombia and Ecuador. Hail

results from powerful convection currents in the tropics, especially in

the spring, and does much damage to bananas.

Soil

The banana plant will grow and fruit under very poor conditions but

will not flourish and be economically productive without deep,

well-drained soil—loam, rocky sand, marl, red laterite,

volcanic ash, sandy clay, even heavy clay—but not fine sand

which holds water. Over head irrigation is said to improve the tilth of

heavy clay and has made possible the use of clay soils that would never

have been considered for banana culture in the past. Alluvial soils of

river valleys are ideal for banana growing. Bananas prefer an acid soil

but if the pH is below 5.0 lime should be applied the second year. Low

pH makes bananas more susceptible to Panama disease. Where waterlogging

is likely, bananas and plantains are grown on raised beds. Low,

perennially wet soils require draining and dry soils require irrigation.

Propagation

Banana seeds are employed for propagation only in breeding programs.

Corms are customarily used for planting and Mexican studies with 'Giant

Cavendish' have shown that those over 17.5 lbs (8 kg) in weight come

into bearing early and, in the first year, the bunches are longer,

heavier, with more hands than those produced from smaller corms. From

the second year on, the advantage disappears. Most growers prefer

"bits" 2- to 4-lb (0.9-1.8 kg) sections of the corm. When corms are

scarce, smaller sections—1 to 2 lbs (454-908 g) have been

utilized and early fertilization applied to compensate for the smaller

size. But in Queensland it is specified that "bits" of 'Dwarf

Cavendish' shall not be less than 4 x 3 x 3 in (10 x 7.5 x 7.5 cm) and

"bits" of 'Lady Finger' and other tall cultivars shall be not less than

5 x 5 x 3 1/2 in ( 12.5 x 12.5 x 9 cm). The corm has a number of buds,

or "eyes", which develop into new shoots. The two upper buds are the

youngest and have a pinkish tint. These develop rapidly and become

vigorous plants. To obtain the "bits", a selected, healthy banana

plant, at least 7 months old but prior to fruiting, is uprooted and cut

off about 4 to 5 in (10-12.5 cm) above the corm. The outer layer of

leaf bases is peeled off to expose the buds, leaving just a little to

protect the buds during handling and transport. The corm is split

between the 2 upper buds and trimmed with square sides, removing the

lower, inferior buds and any parts affected by pests or disease,

usually indicated by discoloration. Then the "bits" are fumigated by

immersing for 20 minutes in hot water at about 130°F

(54.44°C) or in a commercial nematicide solution. Sometimes it

is advisable to apply a fungicide to prevent spoilage. They should then

be placed in a sanitary place (away from all diseased trash) in the

shade for 48 hrs before planting.

Inasmuch as "bits" are not often

available in quantity, the second

choice is transplantation of suckers. These should not be too young nor

too old.

The sucker first emerges as a conical shoot which opens and releases

leaves that are mostly midribs with only vestiges of blade. These

juvenile leaves are called "sword", "spear", or "arrow", leaves. Just

before the sucker produces wide leaves resembling those of the mature

plant but smaller, it has sufficient corm development to be

transplanted. Sometimes suckers from old, deteriorating corms have

broad leaves from the outset. These are called "water" suckers, are

insubstantial, with very little vigor, and are not desirable

propagating material. "Maiden" suckers that have passed the

"sword"-leaved stage and have developed broad leaves must be large to

be acceptably productive. In banana trials at West Bengal, India,

suckers 3 to 4 months old with well-developed rhizomes proved to be the

best yielders. In comparison, small, medium, or large "sword" suckers

develop thicker stems, and give much higher yields of marketable fruits

per land parcel. "Bits' grow slowly at first, but in 2 years' time they

catch up to plants grown from suckers or "butts" and are much more

economical. "Butts" (entire corms, or rhizomes, of mature plants),

called "bull heads" in the Windward Islands, are best used to fill in

vacancies in a plantation. For quick production, some farmers will use

"butts" with several "sword" suckers attached. Very young suckers,

called "peepers", are utilized only for establishing nurseries.

Instead of waiting for normal sucker development, multiplication has

been artificially stimulated in the field by removing the soil and

outer leaf sheaths covering the upper buds of the corm, packing soil

around them and harvesting them when they have reached the "sword'

sucker stage. A greenhouse technique involves cleaning and injuring a

corm to induce callus formation from which many new plants will

develop. As many as 180 plantlets have been derived from one corm in

this manner.

Diseases are often spread by vegetative propagation of bananas, and

this fact has stimulated efforts to create disease-free planting

material on a large scale by means of tissue culture. Some commercial

banana cultivars have been cultured in Hawaii. A million 'Giant

Cavendish' banana plants were produced by meristem culture in Taiwan in

1983. In the field, these laboratory plantlets showed 95% survival,

grew faster than suckers in the first 5 months, had bigger stems and

more healthy leaves.

Rapid multiplication of 'Philippine Lacatan' and 'Grand Naine' bananas,

and the Sigatoka-resistant 'Saba' and 'Pelipita' plantains by shoot-tip

culture has been achieved by workers at State University of New York.

Culture

On level land where the soil is compact, deep ploughing is needed to

improve aeration and water filtration, whereas on a sloping terrain

minimum tillage is advised as well as contouring of rows to minimize

erosion. Planting is best done at the end of the dry season and

beginning of the wet season for adequate initial moisture and to avoid

waterlogging of the young plants. Puerto Rico, because of its favorable

climate, is able to make monthly plantings of plantains the year around

in order to produce a continuous supply for processing factories.

However, some consideration has been given to manipulation of planting

dates to avoid a summer surplus (June-September) caused by March and

May plantings and to take advantage of higher prices in winter and

spring (February to April). To achieve this, it is suggested that

plantings be made only in the first or second weeks of January, July,

September, November and December. Generally, the banana requires 10 to

12 months from planting to harvest. Summer plantings of plantains in

Puerto Rico take 14 to 16 months; winter plantings 17 to 19. In regions

where there may be periods of low temperatures in winter, planting time

is chosen to allow flowering and fruiting before predictable cold

periods.

Spacing varies with the ultimate size of the cultivar, the fertility of

the soil, and other factors. Close planting protects plantations

exposed to high winds, but results in fewer suckers, hinders disease

control, and has been found to be profitable for only the first year.

In subsequent years, fruits are shorter, the flesh is softer and

bunches ripen prematurely. The standard practice in Puerto Rico is 500

plants of 'Maricongo' plantain per acre (1,235 plants/ha). Increasing

to 800 plants/acre (1,976/ha) has increased yield by 4 tons, but

elevating density to 1,300 plants/acre (3,212 plants/ha) has not shown

any further increase. In Surinam, most of the plantains are grown at a

density of 809 to 1,012 plants per acre (2,000-2,500/ha), but density

may range from 243 to 1,780 plants per acre (600-4,400/ha).

The higher the number of plants in the field, the larger the volume of

fertilizer that must be applied. The crop suffers severely from root

competition, for the roots of a fully grown banana plant may extend

outward 18 ft (5.5 m). The higher the altitude, the lower the density

must be because solar radiation is reduced. Too much space between

plants allows excessive evaporation from uncovered soil and increases

the weed problem. Growers must determine the most economical balance

between sufficient light for good yields and efficient land managemeet.

Spacing distances for 'Dwarf Cavendish' range from 10 x 6 ft (3 x 1.8

m) to 15 x 12 ft (4.5 x 3.6 m). A spacing of 12 ft (3.6 m) between rows

and 8 ft (2.4 m) between plants allows 450 plants per acre (1,112

plants/ha). Studies conducted with the so called 'Lacatan' ('Pisang

masak hijau') over a 3-year period in Jamaica, demonstrated the optimum

density to be 680 plants per acre (2,680/ha). At closer spacings, yield

increased but profits declined. Hexagonal spacing gives the maximum

number of plants per area. Double- and triple-row plantings provide

alleys for mechanical operations and harvesting.

Planting holes should be at least 18 in (45 cm) wide and 15 in (38 cm)

deep, but may be as much as 3 ft (0.91 m) wide and 2 ft (0.6 m) deep

for extra wind resistance. They should be enriched in advance of

planting. On hillsides, suckers are set with the cut surface facing

downhill; the bud or "eye" of a "bit" must point uphill; so that the

"follower" sucker will emerge on the uphill side where the soil is

deepest. A surface cover of about 4 in (10 cm) of soil is trampled down

firmly.

Weed control is essential. Geese have been installed as weeders because

they do not eat the banana plants. However, they consume mostly grass

and fail to eliminate certain broad-leaved weeds which still require

cleaning out. Certain herbicides, including Diuron and Ametryne, have

been approved for banana fields. They are applied immediately after

planting but great care must be taken to minimize adverse effects on

the crop. Ametryne has been shown to be relatively safe for the plants

and it has a short life in the soil. The most persistent weed is Cyperus rotundus L.

(nutgrass, yellow nutgrass, purple nutsedge, coqui or coyolillo) which

decreases yields and competes with the crop for nitrogen.

In some plantations, a mulch of dry banana leaves is maintained to

discourage weeds. Some growers resort to live groundcovers such as Glycine javanica L.

(Rhodesian kodzu), Commelina

spp., or Zebrina pendula

Schnizl. or other creepers, but these tend to climb the banana stems

and become a nuisance. Sometimes short-term crops are interplanted in

young banana fields, for example, maize, eggplant, peppers, tomatoes,

okra, sweetpotato, pineapple or upland rice. A space of at least 3 ft

(0.91 m) must be kept clear around each banana plant. However, there

are banana authorities who are opposed to interplanting.

Bananas and plantains are heavy feeders. It has been calculated that a

harvest of 5 tons of fruit from an acre leaves the soil depleted by 22

lbs (10 kg) nitrogen, 4 lbs (1.8 kg) phosphorus, 55 lbs (25 kg) potash

and 11 oz (312 kg) calcium. In general, it can be said that banana

plants have high nitrogen and phosphorus requirements and a fertilizer

formula of 8:10:8 NPK is usually suitable and normally 1 to 1 1/2

tons/acre (1 1 1/2 MT/ha) may be adequate. One-third of the fertilizer

is worked into each planting site when most of the plants appear above

ground, one third in a circle about 1 ft (30 cm) out from each plant 2

months later, and one-third at double the distance 2 months after that.

Supplementary feedings will depend on signs of deficiencies (often

determined by leaf analyses) as the plantation develops. Fertilization

needs vary with the soil. In Puerto Rico, most plantains are grown on

humid Oxisols and Ultisols in the interior. These soils are well

drained but relatively infertile and highly acid, the pH being about

4.8. On such soils, potassium uptake may be too high and N and Mg

deficiencies occur. But experts have shown that these soils respond to

good fertilization practices and can be very productive. As an example,

224 lbs N per acre (224 kg/ha) applied in circular bands 1.5 ft (0.46

m) from the base of the pseudostem gives a significantly higher yield

than broadcast N, and there is good response to Mg applied at time of

planting and again 7 months later.

In the humid mountain regions of Puerto Rico, 250 to 325 lbs N per acre

(250 325 kg/ha), 125 to 163 lbs phosphorus per acre (125 163 kg/ha),

and 500 to 650 lbs potassium per acre (500 650 kg/ha) are recommended

for plantains. On lowland sandy clay, phosphorus and magnesium

applications appear ineffective. Applications of N at the rate of 168

to 282 lbs/acre (168-282 kg/ha) increase size and number of fruits

harvested, but higher rates of N decrease yield because of the number

of plants that bend over halfway or are stunted or fail to flower.

Applications of 1,121 1bs N per acre (1,121 kg/ha) reduce production by

46%. Potassium at the rate of 405 to 420 lbs/acre (405 420 kg/ha) has

the effect of increasing weight and number of fruits. However, there

appear to be factors, possibly soil magnesium and calcium, which

inhibit the uptake of potassium. One study showed that it took one year

for heavy applications of K to reach down to a depth of 8 in (20 cm)

where most of the roots were found in a banana plantation on clay loam.

One benefit of added potassium is that it makes bananas more buoyant.

In cool, dry seasons in Honduras, the fruit tissue is abnormally dense

and there is a high rate of "sinkers" when hands are floated through a

washing tank. Such fruits have been found deficient in potassium and

increased potassium in the fertilizer has reduced the problem.

Irrigation by costly overhead sprinkler systems is standard practice in

large scale banana culture in Central America. Without such equipment,

irrigation basins may be necessary throughout the field and they should

be able to hold at least 3 in (7.5 cm) of water. During the first 2

months, the plants should be irrigated every 7 to 10 days; older plants

need irrigation only every 3 to 4 weeks in dry seasons. On heavy soils,

too frequent irrigations decrease yields. For maximum root development,

the water table must be between 14 and 19 in (36 48 cm) below ground

level.

To preserve the original density, the plants are pruned; that is, only

the most deep seated sucker and one or more of its offshoots

("peepers") are permitted to exist beside each parent plant to serve as

replacements and maintain a steady succession. All other suckers are

killed to prevent competition with the pseudostem and its "followers",

and a bunch of fruits will be ready for harvest every 6 to 8 months.

Various methods of de-suckering have been employed: 1) wrenching by

hand; 2) cutting at soil level with a banana knife; 3) cutting at soil

level and filling the base with kerosene; 4) cutting at soil level and

killing the under ground terminal bud by thrusting in and twisting a

gouging tool.

As the older leaves wither and droop, they must be removed because they

interfere with spraying, they shade the suckers, cause blemishes on the

fruits, harbor disease, insects and other creatures, and constitute a

fire hazard.

Bearing bananas require propping. This has been done with simple wooden

or bamboo poles, forked poles, or two stakes fastened together to form

an "X" at the top, a system much less harmful to the pseudostem. Or the

plant may be tied back to pickets driven into the ground, to prevent

falling with the weight of the bunch.

Fig. 10: Immature banana bunch ("stem") in protective plastic cover;

Hacienda Secadal, Ecuador.

Various types of covering—dry banana leaves, canvas, drill

cloth, sisal sacks, or burlap or so-called "Hessian' bags (made of

jute), have been put over banana bunches intended for export,

especially to enhance fruit development in winter and avoid blemishes.

In 1955, Queensland led the trend toward adoption of tubular poly

vinylchloride (PVC), then the cheaper blue polyethylene covers after

trials produced record bunches. At first, the transparent covering

caused sunburn on the first two hands and it was found necessary to

protect these with newspaper before pulling on the plastic sleeve. The

use of plastic covers became standard practice not only in Australia

but in Africa, India and the American tropics. In 1963, Queensland

growers were turning to covers made of High Wet Strength

(formaldehyde-treated) kraft paper which was already in use for garbage

bags. These bags were easily stapled at the top, prevented sunburn,

resisted adverse weather, and were reusable for at least another

season. Some growers still prefer the burlap. It is cautioned that the

cover should not be put on until the bracts have lifted from the fruits

(about 21 days after "shooting") so that the young fingers will be firm

enough to resist the friction of the cover.

If bunches are composed of more than 7 hands, debudding, or

"de-belling" that is, removal of the terminal male bud (which keeps on

extending and growing) will result in somewhat fuller bananas, thus

increasing bunch weight. The cut should be made several inches below

the last hand so that the rotting tip of the severed stalk will not

affect the fruits.

Harvesting

Banana bunches are harvested with a curved knife when the fruits are

fully developed, that is, 75% mature, the angles are becoming less

prominent and the fruits on the upper hands are changing to light

green; and the flower remnants (styles) are easily rubbed off the tips.

Generally, this stage is reached 75 to 80 days after the opening of the

first hand. Cutters must leave attached to the bunch about 6 to 9 in

(15-18 cm) of stalk to serve as a handle for carrying. With tall

cultivars, the pseudostem must be slashed partway through to cause it

to bend and harvesters pull on the leaves to bring the bunch within

reach. They must work in pairs to hold and remove the bunch without

damaging it. In the early 1960's a "banana bender" was invented in

Queensland—an 8-ft pole with a steel rod mounted at the top

and shaped with a downward pointing upper hook and an upward-pointing

lower hook, the first to pull the pseudostem down after nicking and the

second to support the bent pseudostem so that the bunch can be cut at a

height of about 4 1/2 ft ( 1.35 m).

Fig. 11: Mature, newly harvested, banana bunches at Hacienda Secadal,

Ecuador.

Formerly, entire bunches were transported to shipping points and

exported with considerable loss from inevitable damage. Improved

handling methods have greatly reduced bunch injuries. In modern

plantations, the bunches are first rested on the padded shoulder of a

harvester and then are hung on special racks or on cables operated by

pulleys by means of which they can be easily conveyed to roads and by

vehicle to nearby packing sheds. Where fields have been located in

remote areas lacking adequate highways, transport out has been

accomplished by hovercraft flying along riverbeds. In Costa Rica, when

rains have prevented truck transport to railway terminals, bananas have

been successfully carried in slings suspended from helicopters.

Exposure to even moderate light after harvest initiates the ripening

process. Therefore the fruits should be protected from light as much as

possible until they reach the packing shed.

In India, studies have been made to determine the most feasible

disposition of a plant from which a bunch has been harvested. It is

normal for it to die and it may be left standing for 3 to 4 months to

dehydrate before removal, or the top half may be removed right after

harest by means of a tool called a "mattock" (a combined axe and hoe);

or the pseudostem may be cut at ground level, split open, and the

tender core taken away for culinary purposes. Results indicated that

the first two practices have equal effect on production, but the

complete felling and removal of the pseudostem lowered the yield of the

"follower" significantly. In Jamaica and elsewhere it is considered

best to chop and spread as organic matter the felled pseudostem and

other plant residue. This returns to the soil 404 lbs N, 101 lbs P and

1, 513 lbs K from an acre of bananas (404 kg, 101 kg and 1,513 kg,

respectively, from a hectare). The stump should be covered with

hard-packed soil to discourage entrance of pests.

Banana plantations, if managed manually, may survive for 25 years or

far longer. The commercial life of a banana "stool" is about 5 or 6

years. From the 4th year on, productivity declines and the field

becomes too irregular for mechanical operations. Sanitary regulations

require that the old plantings be eradicated. In the past, this has

been done by digging out the plants with the mattock, or bringing in

cattle to graze on them. In recent years, the old plants and the

suckers that arise from the old corms are injected with herbicide until

all are thoroughly killed and the field is then cleared. Where bananas

or plantains are raised on cleared forest land without sophisticated

maintenance practices, they become thoroughly infested with nematodes

by the end of the third year and the regrowth of underbrush has begun

to take over the field, so it is simply abandoned.

Yield

It is clear that many factors determine the annual yield from a banana

or plantain plantation: soil and agronomic practices, the cultivar

planted, spacing, the type of propagating material and the management

of sucker succession. The 'Gros Michel' banana has yielded 3 to 7 tons

per acre (3 to 7 MT/ha) in Central America. A 'Giant Cavendish' bunch

may weigh 110 lbs (50 kg) and have a total of 363 marketable fruits. A

well-filled bunch of "Dwarf Cavendish' will have no more than 150 to

200 fruits. Sword suckers of plantains have yielded 54,984 fruits per

acre (135,866 fruits /ha); water suckers, 49,021 fruits per acre

(121,132 fruits/ha).

With heavy fertilization, the 'Maricongo' plantain in Puerto Rico,

planted at the rate of 725 per acre has produced 21,950 fruits per acre

(54,238 fruits/ha); at the rate of 1,450 per acre has produced 39,080

fruits per acre (96,369 fruits/ha); in a single year.

In 1981, investigators of the earnings of plantain producers in Puerto

Rico found that traditional farmers had costs of $1,568.00 per acre

($3,874.59/ha); gross income of $2,436.90 per acre ($6,021.58/ha); and

net profit of $868.88 per acre ($2,146.99/ha). Those farmers who had

adopted improved techniques for preparing the field, weeding and

control of pests and diseases had a cost of $2,132.14 per acre

($5,268.52/ha); gross income of $4,253.26 per acre ($10,509.81/ha); and

net profit of $2,121.12 per acre ($5,241.29/ha).

'Maricongo' plantains spaced at 5 x 5 ft (1.5 x 1.5 m), 1,742

plants/acre (4,303 plants/ha), have produced 33.4 tons per acre (73.5

tons/ha) over a period of 30 months.

Handling and

Packing

Banana bunches were formerly padded with leaf trash which absorbed much

of the sap and latex from the harvesting operation and the sites of

broken off styles, each of which can leak at least 6 drops, especially

if bunches are cut early in the morning. In the 1960's, when whole

bunches were being exported from the Windward Islands and Jamaica to

England, they were wrapped in wadding (paperbacked layers of paper

tissue) to absorb the latex, and then encased in plastic sleeves for

shipment. Nowadays plastic sleeves left on the bunches help protect

them during transport from the field to distant packing sheds and a

cushion of banana trash on the floor and against the sides of the truck

does much to reduce injury. But the plastic bags increase the problem

of staining by the sap/latex which mingles with the condensation inside

the bag, becomes more fluid, runs down the inside and stains the peel.

When hands are cut off, additional sap/latex mixture oozes from the

severed crown. Banana growers and handlers know that this substance

oxidizes and makes an indelible dark-brown stain on clothing. It

similarly blemishes the fruits. At packing stations, the hands are

floated through water tanks to wash it off. (Sodium hydrochlorate is an

effective solvent.) Some people maintain that the fruit should remain

in the tank for 30 minutes until all oozing of latex ceases. At certain

times of the year, up to 5% of the hands may sink to the bottom of the

tank, become superficially scarred and no longer exportable. As

mentioned earlier, increased potassium in fertilizer mixtures renders

the bananas more buoyant and fewer hands sink. In rainy seasons, it may

be necessary to apply fungicide on the cut crown surface to avoid

rotting, though experiments have shown that some fungicides give an

off-flavor to the fruit.

Boxing was experimented with in the late 1920's but abandoned because

of various types of spoilage. Modern means of combatting the organisms

that cause such problems, as well as better systems of handling and

transport, quality control, and good container design, have made carton

packing not only feasible but necessary. First, the hands are graded

for size and quality and then packed in layers in special ventilated

cartons with plastic padding to minimize bruising.

In the past, bananas for export from Fiji to New Zealand were detached

individually from the hands and packed tightly in 72-lb (33 kg) wooden

boxes, with much bruising of the upper layer and of the fruits in

contact with the sides. Reduction of fruit quality was found to offset

the economic advantage of filling all the shipping space with fruits.

Wooden boxes were abandoned and suppliers were converted to the packing

of hands with cushioning material.

Controlled

Ripening and Storage

At times, markets may not be able to absorb all the bananas or

plantains ready for harvest. Experiments have been conducted to

determine the effect of applying gibberellin, either by spraying or in

the form of a lanolin paste, on the stalk just above the first hands,

or by injection of a solution, powder or tablet into the stalk. In

Israel, gibberellin A4A7, applied by any of these methods about 2

months before time of normal ripening, had the effect of delaying

ripening from 10 to 19 days. If applied too early, the gibberellin

treatment has no effect.

Harvested bananas allowed to ripen naturally at room temperature do not

become as sweet and flavorful as those ripened artificially. Post

harvest ripening is expedited undesirably if bunches or hands are

stored in unventilated polyethylene bags. As a substitute for expensive

controlled-temperature storage rooms, researchers in Thailand have

found that hands treated with fungicide can be stored or shipped over a

period of 4 weeks in polyethylene bags if ethylene absorbing

vermiculite blocks (treated with a fresh solution of potassium

permanganate) are included in the sack. The permanganate solution will

be ineffective if exposed to light and oxygen. The blocks must be

encased in small polyethylene bags perforated only on one side to avoid

staining the fruits.

Bananas are generally ripened in storage rooms with 90 to 95% relative

humidity at the outset, later reduced to 85% by ventilation: and at

temperatures ranging from 58° to 75°F

(14.4°-23.9°C), with 2 to 3 exposures to ethylene gas

at 1: 1000, or 6 hourly applications for 1 to 4 days, depending on the

speed of ripening desired. The fruit must be kept cool at 56°

60°F (13.3°-15.6°C) and 80 to 85% relative

humidity after removal from storage and during delivery to markets to

avoid rapid spoilage. Post-ripening storage at 70°F

(21°C) in air containing 10 to 100 ppm ethylene accelerates

softening but the fruits will remain clear yellow and attractive with

few or no superficial brown specks.

Plantains for processing in the ripe stage or marketing fresh must be

stored under conditions that will provide the best quality of finished

product. Puerto Rican studies have shown that uniform ripening is

achieved in 4 to 5 days by storage at 56° to 72°F

(13.3°-22.2°C), 95 to 100% relative humidity, and with

a single exposure to ethylene gas. The initial 4% starch content is

reduced to 1 to 1.74% and sugars increase by about 2%. The ripe fruit

can be held another 6 days at 56°F (13.3°C) and still

be acceptable for processing.

The manufacture of products from the green, still starchy, plantain is

a major industry in Puerto Rico. If held at room temperature, the

fruits begin to ripen 7 days after harvest and become fully ripe at the

end of 2 more days. Chemically disinfected fruits stored in

polyethylene bags with an ethylene absorbent (Purefil wrapped in porous

paper) keep 25 days at room temperature of 85°F

(29.44°C), and for 55 days under refrigeration at 55°F

(12.78°C). Products of such fruits have been found to be as

good as or better than those made from freshly harvested green

plantains.

The potential benefits of waxing have been considered by various

investigators. While it is true that waxing of pre-disinfected fruits

prolongs storage life by 60% at room temperature,

78°-92°F (25.56°-33.33°C), and by 28%

at 52° to 55°F (11.11°-12.78°C), there

is no advantage in waxing if the fruits can be held in gas storage, a

combination of waxing and gassing being no better than gassing alone.

In fact, waxing may result in uneven ripening after storage.

In the mid 1960's, fumigation by ethylene dibromide (EDB) against fruit

fly infestation was authorized to permit export of Hawaiian bananas to

the mainland USA. The treatment accelerated ripening and it could not

be applied to 'Dwarf Cavendish' without covering the bunch with opaque

or semi-opaque material for at least 2 months prior to harvest. EDB is

no longer approved for use on food products for marketing within the

United States.

Pests

Wherever bananas and plantains are grown, nematodes are a major

problem. In Queensland, bananas are attacked by various nematodes that

cause rotting of the corms: spiral nematodes—Scutellonema brachyurum,

Helicotylenchus

multicinctus and H.

nannus; banana root-lesion nematode, Pratylenchus coffaea,

syn. P. musicola;

and the burrowing nematode, Radopholus

similis less than 1 mm long, which enters roots and corms,

causing red, purple and reddish-black discoloration and providing entry

for the fungus Fusarium

oxysporum. And also prevalent is the root-knot

nematode, Meliodogyne

javanica.

Plantains in Puerto Rico are attacked by 22 species of nematodes. The

most injurious is the burrowing nematode and it is the cause of the

common black headtoppling disease on land where plantains have been

cultivated for a long time. Wherever coffee has been grown, Pratylenchus coffaea

is the principal nematode, and where plantains have been installed on

former sugar cane land, Meliodogyne

incognita is dominant. These last two are among the three

most troublesome nematodes of Surinam, the third being Helicotylenchus

spp., especially H.

multicinctus.

Nematicides, properly applied, will protect the crop. Otherwise, the

soil must be cleared, plowed and exposed to the sun for a time before

planting. Sun destroys nematodes at least in the upper several inches

of earth. Some fields may be left fallow for as long as 3 years.

Rotating plantains with Pangola grass (Digitaria decumbens)

controls most of the most important species of nematodes except Pratylenchus coffaea.

All planting material must be disinfected—corms, or parts of

corms, or the bases of suckers. There are various means of

accomplishing this. In Hawaii, corms are immersed in water at

122°F (50°C) for 15 minutes and soaked for 5 minutes in

1% sodium hypochlorite. In Puerto Rico, nematodes are combatted by

immersing plantain corms in a solution of Nemagon for 5 minutes about

24 hours before planting and, when planting, mixing the soil in the

hole with granular Dasanit (Fensulfothion) and every 6 months applying

Dasanit in a ring around the pseudostem.

In Queensland, corms are immersed in hot water-131°F

(55°C)—for 20 minutes or solutions of nonvolatile

Nemacur or Mocap. Hot water and Nemacur are equally effective but hot

water has less adverse effects on plant vigor. The Australians believe

that nematicidal treatment of corms must be preceded by peeling off 3/8

in (1 cm) of the outer layer (usually discolored) even though this

diminishes the vigor of the planting material. However, tests with

'Maricongo' plantain corms in Puerto Rico indicate that immersing for

10 minutes in aqueous solutions of Carbofuran, Dasanit, Ethoprop, or

Phenamiphos without the time consuming and possibly detrimental peeling

reduces the initial nematode populations by about 95 % and all the

nematicides except Carbofuran give adequate post-planting control.

Carbofuran apparently does not penetrate deeply enough. The Florida

spiral nematode is the most damaging nematode in Brazil and Florida,

especially during hot, rainy summers. Ethoprop is the only nematicide

registered for use on bananas in Florida but it is not effective

against this pest. The hot water treatment must be employed.

The black weevil, Cosmopolites

sordidus, also called banana stalk borer, banana weevil

borer, or corm weevil, is the second most destructive pest of bananas

and plantains. It attacks the base of the pseudostem and tunnels

upward. A jelly like sap oozes from the point of entry. It was formerly

controlled by Aldrin, which is now banned. In Surinam it has been

combatted by injecting pesticide into the pseudostem, or spraying the

pseudostem with Monocrotophos. In Ghana, they dip planting material in

a solution of Monocrotophos and apply dust of Dieldrin or Heptachlor

around the base of the pseudostem. Puerto Rican tests of several

pesticides have shown that Aldicarb 10G, a nematicide insecticide,

applied at the base of plantain plants at the rate of 1 to 1 1/2 oz

(30-45 g) every 4 months, or 1 oz (30 g) every 6 months, controls both

the burrowing nematode and the black weevil. Biological control of

black weevil utilizing a weevil predator, Piaesius javanus, has not

been successful.

The banana rust thrips, Chaetanophothrips

orchidii; syn. C.

signipennis, stains the peel, causes it to split and

expose the flesh which quickly discolors. The pest is usually partially

controlled by the spraying of Dieldrin around the base of the

pseudostem to combat the banana weevil borer, because it pupates in the

soil. Another measure has been to treat the inside of polyethylene

bunch covers with insecticidal dust, especially Diazinon, before

slipping them over the bunches. It is recognized that this procedure

constitutes a health hazard to the workers. A great improvement is the

introduction of polyethylene bags impregnated with 1% of the

insecticide Dursban, eliminating the need for dusting. Bunches enclosed

in these bags have been found 85.% free of attack by the banana rust

thrips. The bags retain their potency for at least a year in storage.

Impregnated with 1 to 2% Dursban, they are equal to Diazinon in

preventing banana injury by the banana fruit scarring beetle, Colaspis hypochlora,

also called coquito. This pest invades the bunches when the fruits are

very young. It has been very troublesome in Venezuela, and at times

from Guyana to Mexico. The banana scab moth, Nacoleia octasema,

infests

the inflorescence from emergence to the time half the bracts have

lifted. It is a major pest in North Queensland, Malaysia and the

southwest Pacific. Control may be by injection or dusting with

pesticide, sometimes with lifting or removal of bracts. Corky scab of

bananas in southern Queensland is caused by the banana flowers thrips,

Thrips florum,

especially in hot, dry weather. The infestation is

lessened by removal of the terminal male bud which tends to harbor the

pest.

Among minor enemies in Queensland is the banana spider mite, Tetranychus lambi

which moves from beneath the leaves to the fruits in warm weather and

creates dull brown specks which may become so numerous as to completely

cover the peel, causing it to dehydrate and crack irregularly. The

leaves of the plant will wilt. Bi-weekly sprayings of pesticide get rid

of the mites.

The banana silvering thrips, Hercinothrips

bicintus, causes silvery patches on the peel and dots them

with shiny black specks of excrement. The rind-chewing caterpillar, Barnardiella sciaphila,

usually does little damage. Two species of fruit fly—Strumeta tryoni and

S. musae

—occasionally attack bananas in North Queensland.

Diseases

The subject of diseases is authoritatively presented by C.W. Wardlaw in

the second edition of his textbook, Banana Diseases, including

plantains and abaca, 1972; 878 pages.

It is appropriate here only to mention the main details of those

maladies which are of the greatest concern to banana and plantain

growers. Sigatoka, or leaf spot, caused by the fungus Mycosphaerella musicola

(of which the conidial stage is Cercospora

musae) was first reported in

Java in 1902, next in Fiji in 1913 where it was named after the

Sigatoka Valley. It appeared in Queensland 10 years later, and in

another 10 years made its appearance in the West Indies and soon spread

throughout tropical America. The disease was noticed in East and West

Tropical Africa in 1939 and 1940. It was discovered in Ghana in 1954

and ravaged a state farm in 1965. It is most prevalent on shallow,

poorly drained soil and in areas where there is heavy dew. The first

signs on the leaves are small, pale spots which enlarge to 1/2 in (1.25

cm), become dark purplish black and have gray centers. When the entire

plant is affected, it appears as though burned, the bunches will be of

poor quality and will not mature uniformly. The fruits will be acid,

the plant roots small. Control is achieved by spraying with orchard

mineral oil, usuall every 3 weeks, a total of 12 applications of 1 1/2

gals per acre (14.84 liters/ha); or by systemic fungicides applied to

the soil or by aerial spraying.

A much more virulent malady, Black Sigatoka, or Black Leaf Streak,

caused by Mycosphaerella

fifiensis var. difformis,

attacked bananas in Honduras in 1969 and spread to banana plantations

in Guatemala and Belize. It appeared in plantations in Honduras in 1972

where there had not been any need to spray against ordinary Sigatoka.

It made headway rapidly through plantain fields in Central America to

Mexico and about 10 years later was found in the Uruba region of

Colombia. The disease struck Fiji in 1963 and became an epidemic. It

began spreading in 1973, largely replacing ordinar Sigatoka. Surveys

have revealed this previously unrecognized disease on several other

South Pacific islands, in Hawaii, the Philippines, Malaysia and Taiwan.

It is spread mostly by wind; kills the leaves and exposes the bunches

to the sun. Cultivars which are resistant to Sigatoka have shown no

resistance to Black Sigatoka. There are vigorous efforts to control the

disease by fungicides or intense oil spraying. But it is not completely

controlled even by spraying every 10 to 12 days a total of 40

sprayings. The cost of control with fungicides is 3 to 4 times that of

controlling ordinary Sigatoka because of the need for more frequent

aerial sprayings. It is very difficult to treat properly on islands

where bananas are grown mostly in scattered plantings. In Mexico where

plantains are extremely important in the diet, and 65% of the

production is on non-irrigated land, control efforts have elevated

costs of plantain production by 145 to 168%. In the Sula Valley of

Honduras, Black Sigatoka has caused annual losses of 3,000,000 boxes of

bananas. The great need is for resistant cultivars of high quality.

Panama Disease or Banana Wilt, which arises from infection by the

fungus, Fusarium

oxysporum f. sp. cubense

originates in the soil, travels to the secondary roots, enters the corm

only through fresh injuries, passes into the pseudostem; then,

beginning with the oldest leaves, turns them yellow first at the base,

secondly along the margins, and lastly in the center. The interior

leaves turn bronze and droop. The pseudostem turns brown inside. This

plague has seriously affected banana production in Central America,

Colombia and the Canary Islands. It started spreading in southern

Taiwan in 1967 and has become the leading local banana disease. The

'Cavendish' types have been considered highly resistant but they

succumb if planted on land previously occupied by 'Gros Michel'. The

disease is transmitted by soil, moving agricultural vehicles or other

machinery, flowing water, or by wind. It is combatted by flooding the

field for 6 months. Or, if it is not too serious, by planting a cover

crop. There are reportedly two races: Race #1 affects 'Gros Michel',

'Manzano', 'Sugar' and 'Lady Finger'; Race #2 attacks 'Bluggoe'.

Resistant cultivars are the Jamaican 'Lacatan', 'Monte Cristo', and

'Datil'or'Nino'. Resistant plantains are 'Maricongo', 'Enano' end

'Pelipita'.

Moko Disease, or Moko de Guineo, or Marchites bacteriana,

is caused by

the bacterium, Pseudomonas

solanacearum, resulting in internal decay. It has become

one of the chief diseases of banana and plantain in the western

hemisphere and has seriously reduced production in the leading areas of

Colombia. It attacks Heliconia species as well. It is transmitted by

insects, machetes and other tools, plant residues, soil, and root

contact with the roots of sick plants. There are said to be 4 different

types transmitted by different means. Efforts at control include

covering the male bud with plastic to prevent insects from visiting its

mucilaginous excretion; debudding, disinfecting of cutting tools with

formaldehyde in water 1: 3; disinfection of planting material; disposal

of infected fruits and plant parts; injection of herbicide into

infected plants to hasten dehydration, and also seemingly healthy

neighboring plants. If the organism is variant SFR, all adjacent plants

within a radius of 16.5 ft (5 m) must be destroyed and the area not

replanted for 10 to 12 months, for this variant persists in the soil

that long. If it is variant B, the plants within 32.8 ft (10 m) must be

injected and the area not replanted for 18 months. In either case, the

soil must be kept clear of broad leaved weeds that may serve as hosts.

In Colombia, there are 12 species of weeds that serve as hosts or

"carriers" but only 4 of these are themselves susceptible to the

disease. Crop rotation is sometimes resorted to. The only sure defense

is to plant resistant cultivars, such as the 'Pelipita' plantain.

Black-end arises from infection by the fungus Gloeosporium musarum,

of which Glomerella

cingulata is the perfect form. It causes anthracnose on

the plant and attacks the stalk and stalk-end of the fruits forming

dark, sunken lesions on the peel, soon penetrating the flesh and

developing dark, watery, soft areas. In severe cases, the entire skin

turns black and the flesh rots. Very young fruits shrivel and mummify.

This fungus is often responsible for the rotting of bananas in storage.

Immersing the green fruits in hot water, 131°F (55°C)

for 2 minutes before ripening greatly reduces spoilage.

Cigar-tip rot, or Cigar-end disease, Stachylidium (

Verticillium) theobromae

begins in the flowers and extends to the tips

of the fruits and turns them dark, the peel darkens, the flesh becomes

fibrous. One remedy is to cut off withered flowers as soon as the

fruits are formed and apply copper fungicides to the cut surfaces.

In Surinam, cucumber mosaic virus attacks plantains especially when

cucumber is interplanted in the fields. Also, Chinese cabbage, Cayenne

pepper and "bitter greens" (Cestrum

latifolium Lam.) are hosts for the disease.

Cordana leaf spot (Cordana

musae), causes oval lesions 3 in (7.5 cm) or more in

length, brown with a bright-yellow border. There is progressive dying

of the leaves beginning with the oldest, as in Sigatoka, with

consequent undersized fruits ripening prematurely. It formerly occurred

mainly in sheltered, humid regions of Queensland. Now it is seen mostly

as an invader of areas affected by Sigatoka, in various geographical

locations.

Bunchy top, an aphid-transmitted virus disease of banana, was unknown

in Queensland until about 1913 when it was accidentally introduced in

suckers brought in from abroad. In the next 10 years it spread swiftly

and threatened to wipe out the banana industry. Drastic measures were

taken to destroy affected plants and to protect uninvaded plantations.

The disease was found in Western Samoa in 1955 and it eliminated the

susceptible 'Dwarf Cavendish' from commercial plantings. A vigorous

eradication and quarantine program was undertaken in 1956 and carried

on to 1960. Thereafter, strict inspection and control measures

continued. Other crops were provided to farmers in heavily infested

areas. Leaves formed after infection are narrow, short, with upturned

margins and become stiff and brittle; the leafstalks are short and

unbending and remain erect, giving a "rosetted" appearance. The leaves

of suckers and the 3 youngest leaves of the mother plant show yellowing

and waviness of margins, and the youngest leaves will have very narrow,

dark-green, usually interrupted ("dot-and dash") lines on the underside.

Because of the seriousness of Panama disease and Bunchy Top in southern

Queensland, the prospective banana planter must obtain a permit from

the Queensland Department of Primary Industries. In the Southern

Quarantine Area, any plant showing Bunchy Top, as well as its suckers

and all plants within a 15 ft (4.6 m) radius must be killed by

injecting herbicide or must be dug out completely and cut into pieces

no bigger than 2 in (5 cm) wide. In restricted areas, only the immune

'Lady Finger' may be grown. In the Northern Quarantine Area, no plants

may be brought in from another area and all plants within a radius of

120 ft (36.5 m) from a diseased plant must be eradicated.

Swelling and splitting of the corm and the base of the pseudostem is

caused by saline irrigation water and by overfertilization during

periods of drought which builds up soluble salts in the soil.

Food Uses

The ripe banana is utilized in a multitude of ways in the human

diet—from simply being peeled and eaten out of-hand to being

sliced and served in fruit cups and salads, sandwiches, custards and

gelatins; being mashed and incorporated into ice cream, bread, muffins,

and cream pies. Ripe bananas are often sliced lengthwise, baked or

broiled, and served (perhaps with a garnish of brown sugar or chopped

peanuts) as an accompaniment for ham or other meats. Ripe bananas may

be thinly sliced and cooked with lemon juice and sugar to make jam or

sauce, stirring frequently during 20 or 30 minutes until the mixture

jells. Whole, peeled bananas can be spiced by adding them to a mixture

of vinegar, sugar, cloves and cinnamon which has boiled long enough to

become thick, and then letting them cook for 2 minutes.

In the islands of the South Pacific, unpeeled or peeled, unripe bananas

are baked whole on hot stones, or the peeled fruit may be grated or

sliced, wrapped, with or without the addition of coconut cream, in

banana leaves, and baked in ovens. Ripe bananas are mashed, mixed with

coconut cream, scented with Citrus leaves, and served as a thick,

fragrant beverage.

Banana puree is important as infant food and can be successfully canned

by the addition of ascorbic acid to prevent discoloration. The puree is

produced on a commercial scale in factories close to banana fields and

packed in plastic-lined #10 cans and 55-gallon metal drums for use in

baby foods, cake, pie, ice cream, cheesecake, doughnuts, milk shakes

and many other products. It is also used for canning half-and-half with

applesauce, and is combined with peanut butter as a spread. Banana

nectar is prepared from banana puree in which a cellulose gum

stabilizer is added. It is homogenized, pasteurized and canned, with or

without enrichment with ascorbic acid.