Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide

version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Anacardium

occidentale L.

Local Names:

Arabic (habb

al-biladhir); Bengali (hijuli, hijlibadam); Burmese (thiho thayet si);

Chinese (yao kuo); Dutch (kasjoe, mereke); English (cashew, cashew

nut); Filipino (kasoy, balogo, bulabad); French (anacardier, acajou,

pommier cajou, pomme d'cajou, anacadier, noix d'cajou, anacarde,

anacardes, pomme acajou); German (Acajubaum, Kaschubaum, cashwenuß,

elefantenlaus); Gujarati (kaju); Hindi (bojan, kashu-mavu, kaju,

hijuli); Indonesian (jambu monyet, jambu mede); Italian (acagia);

Japanese (kashu nattsu); Javanese (jambu mede, jambu monyet); Khmer

(svaay chanti); Malay (gajus, jambu monyet); Mandinka (kasuowo,

kasuwu); Nepali (kaaju); Portuguese (caju); Sanskrit (kajutaka);

Spanish (cashú, merci, marañón, cacajuil, casho, cajuil, acaya);

Swahili (mkanju, mkorosho, mbibo); Tamil (mindiri); Thai (yaruang,

mamuang, himmaphan, mamuang letlor); Trade name (cashew nut);

Vietnamese (cây diêù, dào lôn hôt)

Family: Anacardiaceae

Botanic

Description

Anacardium

occidentale

is a medium-sized tree, spreading, evergreen, much branched; grows to a

height of 12 m. When grown on lateritic, gravelly, coastal sandy areas,

it rarely exceeds 6 m and develops a spreading habit and globose shape

with crown diameter to 12 m. Grown inland on loams, it reaches 15 m and

is much branched, with a smaller (4- 6 m) crown diameter. The root

system of a mature A.

occidentale,

when grown from the seed, consists of a very prominent taproot and a

well- developed and extensive network of lateral and sinker roots.

Leaves

simple, alternate, coriaceus, glabrous, obovate, rounded at ends, 10-18

x 8-15 cm, with short petiole, pale green or reddish when young and

dark green when mature.

The inflorescence is a terminal

panicle-like cluster commonly bearing male and hermaphroditic flowers.

The male flowers are the most numerous and usually bear 1 exserted

stamen and 9 small inserted ones. A.

occidentale normally comes into flowering in 3 to 5 years.

The

nut, which is the true fruit, dries and does not split open. Inside the

poisonous shell is a large curved seed, nearly 2.5 cm long, the edible

cashew nut. As the nut matures, the stalk (receptacle) at the base

enlarges rapidly within a few days into the fleshy fruitlike structure,

broadest at the apex, popularly known as the fruit. This thin-skinned

edible cashew fruit has a light yellow spongy flesh, which is very

juicy, pleasantly acidic and slightly astringent when eaten raw and

highly astringent when green.

The generic name was given by Linnaeus and refers to the vaguely heart-

shaped look of its false fruit.

Biology

Flies, bees and ants

as well as wind carry out pollination. Bees promote greater pollination

because scented flowers and sticky pollen grains attract them. Bagged

inflorescence does not produce nuts unless it is hand pollination or

insects are allowed inside. Self-pollination is also possible, as nuts

have developed from hand-pollinated, bagged inflorescence.

Ecology

A.

occidentale

requires high temperatures; frost is deleterious. Distribution of

rainfall is more important than the amount of it. The tree fruits well

if rains are not abundant during flowering and if nuts mature in a dry

period; the latter ensures good keeping quality. The tree can adapt to

very dry conditions as long as its extensive root system has access to

soil moisture. In drier areas (800-1000 mm of rainfall), a deep and

well-drained soil without impervious layers is essential.

Biophysical

Limits

Altitude: 0-1000 m, Mean annual temperature: 17-38 deg. C, Mean annual

rainfall: 500-3 500 mm

Soil

types: Prefers deep, fertile, sandy soils but will grow well on most

soils except pure clays or soils that are otherwise impermeable, poorly

drained or subject to periodic flooding.

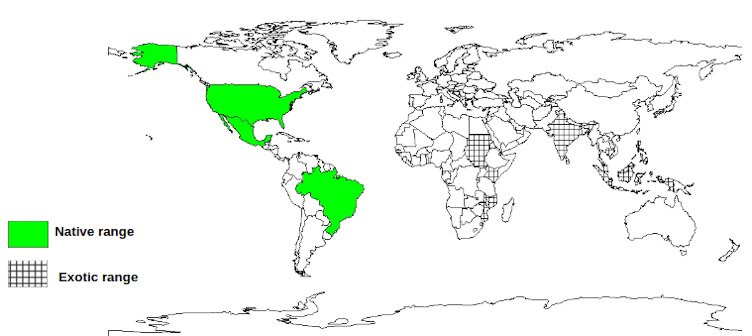

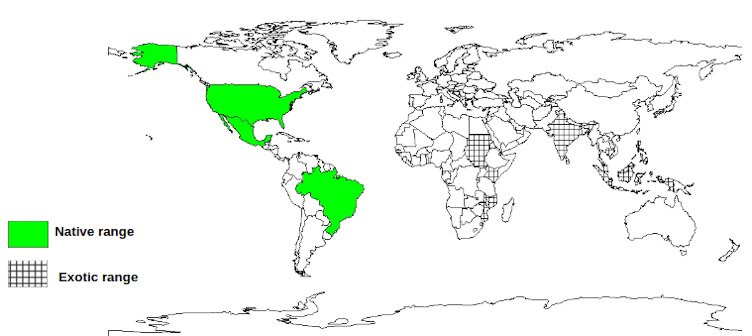

Documented

Species Distribution

Native:

Brazil, Mexico, US

Exotic: Cambodia, Gambia,

India, Indonesia, Kenya, Malaysia, Mozambique, Myanmar, Philippines,

Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Vietnam

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food:

A.

occidentale

is cultivated for its nuts. Botanically, the nut is the fruit; the

cashew apple is the swollen, fleshy fruit stalk. The seeds kernels are

extracted by shelling the roasted nuts. In production areas, cashew

serves as food. Elsewhere it forms a delicacy. The kernels are

nutritious, containing fats, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins and

minerals. In Brazil, Mozambique and Indonesia, the cashew apple is also

important; it is eaten fresh or mixed in fruit salads, and a drink is

prepared from the juice; sweets and jams can also be prepared from it.

Young shoots and leaves are eaten fresh or cooked.

Fodder:

The cake remaining after oil has been extracted from the kernel serves

as animal food. Seed coats are used as poultry feed.

Fibre:

Pulp from the wood is used to fabricate corrugated and hardboard boxes.

Timber:

The wood of A.

occidentale

(‘white mahogany’ in Latin America) is fairly hard with a density of

500 kg/cm. It finds useful applications in wheel hubs, yoke, fishing

boats, furniture, false ceilings and interior decoration. Boxes made

from the wood are collapsible but are strong enough to compete with

conventional wooden packing cases.

Gum or resin:

The bark contains an acrid sap of thick brown resin, which becomes

black on exposure to air. This is used as indelible ink in marking and

printing linens and cottons. The resin is also used as a varnish, a

preservative for fishnets and a flux for solder metals. The stem also

yields an amber-coloured gum, which is partly soluble in water, the

main portion swelling into a jellylike mass. This gum is used as an

adhesive (for woodwork panels, plywood, bookbinding), partly because it

has insecticidal properties.

Tannin or

dyestuff: The acrid sap of the bark contains 3-5% tannin

and is employed in the tanning industry.

Lipids:

An oil, cashew nut shell liquid, is produced in the large cells of the

pericarp; it has industrial applications and is used as a preservative

to treat, for instance, wooden structures and fishing nets. It is also

in good demand for paints, synthetic resins, laminated products, brake

linings and clutch facings.

Alcohol:

In Brazil, Mozambique and Indonesia cashew wine (slightly fermented

juice) is enjoyed at harvest time and can be distilled to produce

strong alcoholic drinks. In Goa, India, fermenting the juice makes a

type of brandy called ‘fenni’. In Tanzania, a product called ‘konyagi’,

akin to gin, is made from cashew apple.

Poison:

One of the components of the bark gum acts as a vesicant and has insect

repellent properties.

Medicine: Cashew syrup is a

good remedy for coughs and colds. Cashew apple juice is said to be

effective for the treatment of syphilis. Root infusion is an excellent

purgative. Old cashew liquor in small doses cures stomach-ache. The oil

obtained from the shell by maceration in spirit is applied to cure

cracks on the sole of the feet, common in villagers. Cashew apple is

anti-scorbutic, astringent and diuretic, and is used for cholera and

kidney troubles. Bark is astringent, counterirritant, rubefacient,

vesicant, and used for ulcer. Cashew nut shell oil is anti-hypertensive

and purgative; it is used for blood sugar problems, kidney troubles,

cholera, cracks on soles of feet, hookworms, corns and warts. The

kernel is a demulcent, an emollient and is used for diarrhoea. Buds and

young leaves are used for skin diseases. The resinous juice of seeds is

used for mental derangement, heart palpitation, rheumatism; it was used

to cure the loss of memory that was a sequel to smallpox.

Services

Reclamation: Because of its extreme tolerance of external conditions,

it has been planted in poor soils to check erosion.

Intercropping:

Has been intercropped with cowpea, groundnuts and horsegram in India.

In Andra Pradesh and Orissa in India, casuarina and coconut constitute

a popular crop combination.

Tree

Management

Weeding

is necessary to conserve soil moisture for the seedlings during the dry

months. After the tree starts bearing, it is important to apply

fertilizers and spray against pests and diseases. Anacardium occidentale

is rarely pruned. Removal of dead and diseased branches is necessary,

however. When an initial closer planting is adopted, thinning is done

after about 5 years. Shape the tree by removing the lower branches to

allow nut collection and human movement.

Germplasm

Management

Seed

storage behaviour is orthodox; 100% germination has been recorded after

4 months of open storage at room temperature, but viability is reduced

to 50% after 10 months and none survives after 13-14 months. Viability

can be maintained for 1 year in storage at room temperature with low

seed mc; viability for more than 3 years in hermetic storage at ambient

temperature with seeds at 11-15% mc.

Pests and

Diseases

A.

occidentale

is susceptible to over 60 known species of insect pests during

different stages of its growth. The major pests in India are considered

to be stem borers and root borers including Plocaederus ferrugineus,

tea mosquito (Helopeltis

antonii), leaf miner (Acrocercops

syngramma) and leaf and blossom webber (Lamida moncusalis).

In Tanzania, important pests include sucking bugs (Helopeltis schoutedeni

and H. anacardii),

the theraptus bug (Pseudotheraptus

wayi), thripts (Selenothrips

rubrocinctus), bark borers (Mecocorynus loripes)

and the defoliating caterpillar (Nudaurelia

bellina).

Common diseases include die-back or pink disease (Corticium salminicola),

damping-off of seedlings (Phytophthora

palmivora); anthracnose disease (Collectotrichum gleosporioides),

leaf spots, shoot-rot and leaf fall. A combination spray of BHC and a

copper fungicide like Blitox at the time of emergence of new flush has

been found an effective prophylactic measure.

Further

Reading

Aiyadura SG, Premanad PP. 1965. Can cashew become a more remunerable

plantation crop? India Cashew Journal.

4(1):2-7.

Anon. 1962. The cultivation of annatto. Farmer Jamaica. 67(5):156-158.

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications &

Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Beentje HJ. 1994. Kenya trees, shrubs and lianas. National Museums of

Kenya.

Cobley L.S & Steele W.M. 1976. An Introduction to the Botany of

Tropical Crops. Longman Group Limited.

Crane JH, Balerdi CF, Campbell CW. 1994. The avocado. Fact Sheet HS-52,

Horticultural Sciences Department,

Florida Cooperative Extension Services, Institute of Food and

Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida.

Dale IR, Greenway PJ. 1961. Kenya trees and shrubs. Buchanan’s Kenya

Estates Ltd.

Hocking D. 1993. Trees for Drylands. Oxford & IBH Publishing

Co. New Delhi.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a

compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4.

IPGRI.

ICRAF. 1992. A selection of useful trees and shrubs for Kenya: Notes on

their identification, propagation and

management for use by farming and pastoral communities. ICRAF.

Jain

SK, Lata S. 1996. Unique indigenous Amazonian uses of some plants

growing in India. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor. 4(3):

21-23.

Katende AB et al. 1995. Useful trees and shrubs for Uganda.

Identification, Propagation and Management for

Agricultural

and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU),

Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Lanzara P. and Pizzetti M. 1978. Simon & Schuster's Guide to

Trees. New York: Simon and Schuster

Mbuya LP et al. 1994. Useful trees and shrubs for Tanzania:

Identification, Propagation and Management for

Agricultural

and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU),

Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Nair KM et. al. 1979. Monograph on plantation crops-1, cashew (Anacardium occidentale

L.). Central Plantations

Institute, Kerala, India.

Nair PK. 1980. Agroforestry species: A crop sheet manual. ICRAF.

Nicholson B.E, Harrison S.G, Masefield G.B & Wallis M. 1969.

The Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford University Press.

Noad T, Birnie A. 1989. Trees of Kenya. General Printers, Nairobi.

Northwood PJ. 1966. Some observations on flowering and fruit setting in

the cashew (Anacardium

occidentale L.). Trop. Agriculture, Trin. 43(1).

Perry LM. 1980. Medicinal plants of East and South East Asia :

attributed properties and uses. MIT Press. South East Asia.

Vaughan JG. 1970. The structure and utilization of oil seeds. Chapman

and Hall Ltd.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Vogt K. 1995. A

field guide to the identification, propagation and uses of common trees

and shrubs of dryland Sudan. SOS Sahel International (UK).

Williams R.O & OBE. 1949. The useful and ornamental plants in

Zanzibar and Pemba. Zanzibar Protectorate

|

|