From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Cashew

Anacardium occidentale L.

The Brazilians are the only people who fully appreciate the cashew.

Father J. S. Tavares, whose studies of Brazilian fruits are probably

the most exhaustive as well as the most interesting which have been

published, says of this tree: "It furnishes food and household remedies

to the poor, a refreshing beverage to the sick, a sweetmeat for tables

richly served, and resin and good timber for industrial uses."

The

readiness with which the cashew grows and fruits in a semi-wild state

has kept it from receiving the horticultural attention which other and

more delicate species have enjoyed. In nearly all regions where it is

grown, it is more common as a naturalized plant than in the fruit

garden. It does not object to such treatment, but multiplies rapidly,

grows vigorously, and yields abundantly of its handsome fruit.

To

see the cashew at its best, one must visit the markets of Bahia or some

other city of the Brazilian coast. Here, during the short season in

which they ripen, immense heaps of cashews are piled up on every side.

Its brilliant shades of color, varying from yellow to scarlet, and its

characteristic and penetrating aroma combine to make this one of the

most enticing of all tropical fruits.

The cashew is a spreading

evergreen tree growing up to 40 feet in height. One of the early

voyagers, Father Simam de Vasconcellos, speaks of it as "the most

handsome of all the trees of America," for which extravagant statement

Father Tavares takes him to task. The cashew cannot fairly be called

handsome; indeed, it is oftentimes awkward or ungainly in habit, with

crooked trunk and branches. The leaves, which are clustered toward the

ends of the stiff branchlets, are oblong-oval or oblongobovate in form,

rounded or sometimes emarginate at the apex, and acute to cuneate at

the base. They vary between 4 and 8 inches in length, and 2 and 3

inches in breadth.

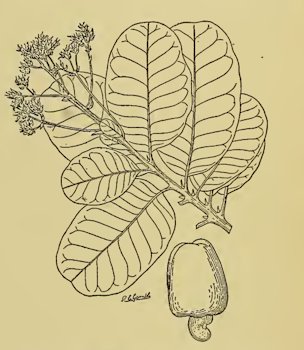

FIG. 22. Foliage, flowers, and fruit of the cashew (Anacardium occidentale).

The

kidneyshaped seed (properly speaking, the fruit) contains an edible

kernel of delicious flavor, while the fleshy portion (fruit-stalk)

above it is filled with aromatic juice, and may be used in many ways.

The

flowers are produced in terminal panicles 6 to 10 inches long. The

cashew, like the mango, is polygamous; that is, some of the flowers are

unisexual (staminate) and others bisexual, both types being produced on

the same panicle. The calyx is five-partite, the corolla 1/3 inch

broad, with five linearlanceolate, yellow-pink petals. The stamens are

usually nine in number, all fertile. The ovary is obovoid, with the

style placed to one side.

The fruit is peculiar. The part which

would be taken for the fruit at first glance is in reality the swollen

peduncle and disk, while the fruit proper is the kidney-shaped

cashew-nut attached to its lower end. The fleshy portion may be termed

the cashew-apple, in order to distinguish it from the true fruit, or

cashewnut. It differs in size, being sometimes as much as 3i inches in

length, while it may be less than 2 inches. The surface is commonly

brilliant yellow or flame-scarlet in color. The skin is a thin

membrane, easily broken ; the flesh light yellow in color and very

juicy. The kidney-shaped nut which is attached to its lower end

contains the single oblong seed.

The cashew was formerly

thought, by some writers at least, to be indigenous both in America and

Asia. It has been shown, however, that it was originally confined to

America, whence it was carried to Asia and Africa by early Portuguese

voyagers. Jacques Huber 1 considered it indigenous on

the campos (plains) and dunes of the lower Amazon region and the north

Brazilian coast in general. It spread very early to other parts of the

tropical American seacoast, and probably was introduced into the West

Indies by the Indians who reached those islands from the South American

mainland before the arrival of Europeans. Gabriel Soares de Souza, one

of the earliest chroniclers of Brazil, found the tree growing both wild

and cultivated on the coast of Bahia in the sixteenth century. He

mentions a "fragrant and delicious wine" which the Indians prepared

from the fruit.

At the present time the cashew is common on the

mainland of tropical America from Mexico to Peru and Brazil. It is

abundant also in the West Indies. In Africa it is found on both the

east and west coasts, and in Madagascar. In southern India it has

become thoroughly naturalized in many of the coastal forests. It is

grown in the Malay Archipelago, and is said to be abundant in Tahiti.

In Hawaii it is not very common.

Regarding its occurrence in India, Dymock, Warden, and Hooper (Pharmacographia Indica) say:

"It

was not known in Goa A.D. 1550; but Christopher a Costa saw it in

Cochin shortly after this. ... In 1653 only a few trees existed on the

Malabar coast; since then it has become completely naturalized on the

western coast, but is nowhere so abundant as in the Goa territory,

where it yields a very considerable revenue. It is planted upon the low

hilly ridges which intersect the country in every direction, and which

are too dry and stony for other crops. The cultivation gives no

trouble, tne jungle being simply cut down to make room for the plants."

In

the United States the culture of this tree is limited to the coast of

Florida, south of Palm Beach and Punta Gorda, approximately. There are

sturdy fruiting trees both at Palm Beach and Miami. In California all

experiments up to the present time have indicated that the climate is

not warm enough for it.

In Mexico and Central America the cashew

is common on the seacoast but is rarely found at elevations higher than

3000 feet. At altitudes of 5000 or 6000 feet the climate appears to be

too cool for the tree.

The English name cashew is an adaptation

of the Portuguese caju. The latter was taken by the earliest settlers

in Brazil from the Tupi name acaju. In the Spanish-speaking countries

of tropical America the usual name is maranon, presumably from the

Brazilian state of Maranhao. The name pajuil is used in Porto Rico,

while in Guatemala the similarity of the cashew to its relative the

mombin (Spondias mombiri) is

recognized in the common name jocote maranon (the mombin being called

simply jocote). In India the form kaju (gajus in the Malayan region)

has appeared, in addition to a number of names not derived from the

American caju. In French the cashew-apple is called pomme d'acajou, and

the nut noix d'acajou. The latter is termed castanha (chestnut) in

Brazil.

In many regions the nut is more extensively used than the apple or fleshy portion. In Brazil this is not the case.

The

cashew-apple is soft, juicy, acid, and highly astringent before

maturity, retaining sufficient astringency when fully ripe to lend it

zest. Owing to its remarkably penetrating, almost pungent aroma, the

jam or sweetmeat made from it possesses a characteristic and highly

pleasing quality. It is also used to supply both a wine and a

refreshing beverage, similar to lemonade, which the Brazilians know as

cajuada. The wine, which is manufactured commercially in northern

Brazil, retains the characteristic aroma and flavor of the fresh fruit.

The preserved fruit in various forms also is an article of commerce.

In

several countries the cashew-nut is produced commercially and exported

to Europe and North America. According to Consul Lucien Memminger,

shipments to the United States from the Madras Presidency in India

during the year 1915 totaled 2288 cwt., valued at $28,063. "About

15,000 cwt. of these nuts are now exported in an average season to

England, France, and America, the principal port of shipment being

Mangalore."

The cashew-nut is kidney-shaped, and about an inch

in length. The soft, thick, cellular shell or pericarp incloses a

slightly curved, white kernel of fine texture and delicate flavor. To

prepare the nuts for eating, they are roasted over a charcoal fire. The

shell contains cardol and anacardic acid substances which severely burn

the mouth and lips of any one who attempts to bite into a fresh nut.

Since these principles are decomposed by heat, the roasted nut can be

eaten without the slightest inconvenience or danger. The kernel is said

to contain: fats 47.13 per cent, nitrogenous matter 9.7 per cent, and

starch 5.9 per cent. An analysis made in Hawaii by Alice R. Thompson

showed the presence of protein to the amount of 14.43 per cent, ash

2.58 per cent, fat 4.56 per cent, and fiber 1.27 per cent.

The

cashew is not particular in regard to the soil on which it grows, but

it is intolerant of frost and can only be cultivated successfully in

regions where temperatures much below the freezing point are rarely

experienced. An account of its culture in southwestern India is given

in the Daily Consular and Trade Reports for November 3, 1914:

"Cashew-nut

trees can be grown successfully on any soil. They thrive in sandy

places as well as on stone, and are not fastidious in point of soil,

but are generally grown where no other crop can be produced. In this

district there are many sand hills, especially below Ghats, which are

utilized for this crop. Along seacoasts which are exposed to severe

gusts of wind, the plants never attain the form of a tree, but keep

along the ground, producing small branches.

"Seeds . . . are

usually planted in the month of June, at a distance of about 15 feet

each way. In many cases this distance proves to be insufficient. The

plants are watered the first year only. No other care is taken of them.

The plantation is usually inclosed by walls.

"The plants begin

to bear from the third year and continue till the age of about fifteen,

at which stage the trees exude a gummy substance in large quantities

and then die."

In other regions the trees live to a greater age

than fifteen years. Reports from many parts of the world indicate that

they may come into bearing the second or third year. P. W. Reasoner

recommended the cashew for cultivation in northern greenhouses, because

of its habit of bearing at an early age.

In Brazil the cashew

flowers in August and September and ripens its fruit from November to

February. In southern India the flowering season is December and

January, and the fruit ripens in March. An Indian writer estimates the

yield of a mature tree at 115 to 150 pounds of fruit yearly. "To get

one maund (28 pounds) of kernels about 1 1/2 candies (115 pounds) of

seed nuts are required."

Very few pests have been reported as affecting the cashew. Father Tavares 2 mentions a fungus parasite which attacks the branchlets, leaves, and flowers at Bahia, Brazil. The redbanded thrips (Heliothrips rubrocinctus

Giard.) sometimes attacks the tree in the West Indies. H.

Maxwell-Lefroy mentions two other species of thrips which have been

found on the cashew in Mysore, India: these are Idolothrips halidaji Newm. and Phloeothrips anacardii Newm.(?).

Seedling

cashew trees differ in the character and quantity of fruit they yield.

In Brazil the trees which produce the largest and finest fruits are

distinguished with varietal names. Some of these trees acquire local

reputations.

Recently P. J. Wester has shown that the cashew can

be shield-budded. By employing this method, it is easily possible to

propagate choice varieties originating as chance seedlings. The reader

is referred to Wester's publication " Plant Propagation in the

Tropics," 2 one of the most valuable contributions which have been made

to tropical pomology.

The method of budding the cashew is

essentially the same as that described in the chapter on the avocado.

Wester says in brief: "Use nonpetioled, mature budwood which is turning

grayish; cut the bud 1 1/2 to 1 3/4 inches long; insert the bud in the

stock at a point of approximately the same age and appearance as the

cion."

1 Boletim do Museu Goeldi, 1904.

2 In Broteria, xiv, January, 1916.

Back to

Cashew Page

|

|