From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Cherimoya

Annona

cherimola Mill.

ANNONACEAE

Certainly the most esteemed of the fruits of the genus Annona (family

Annonaceae), the cherimoya, A.

cherimola

Mill., because of its limited distribution, has acquired few colloquial

names, and most are merely local variations in spelling, such as

chirimoya, cherimolia, chirimolla, cherimolier, cherimoyer. In

Venezuela, it is called chirimorrinon; in Brazil, graveola, graviola,

or grabiola; and in Mexico, pox or poox; in Belize, tukib; in El

Salvador it is sometimes known as anona poshte; and elsewhere merely as

anona, or anona blanca. In France, it is anone; in Haiti, cachiman la

Chine. Indian names in Guatemala include pac, pap, tsummy and tzumux.

The name, cherimoya, is sometimes misapplied to the less-esteemed

custard apple, A.

reticulata L. In Australia it is often applied to the

atemoya (a cherimoya-sugar apple hybrid).

Plate 7: CHERIMOYA, Annona

cherimola

Description

The

tree is erect but low branched and somewhat shrubby or spreading;

ranging from 16 to 30 ft (5 to 9 m) in height; and its young branchlets

are rusty-hairy. The leaves are briefly deciduous (just before spring

flowering), alternate, 2-ranked, with minutely hairy petioles 1/4 to

1/2 in (6 to 12.5 mm) long; ovate to elliptic or ovate-lanceolate,

short blunt-pointed at the apex; slightly hairy on the upper surface,

velvety on the underside; 3 to 6 in (7.5-15 cm) long, 1 1/2 to 3 1/2 in

(3.8-8.9 cm) wide.

Fragrant flowers, solitary or in groups of

2 or 3, on short, hairy stalks along the branches, have 3 outer,

greenish, fleshy, oblong, downy petals to 1 1/4 in (3 cm) long and 3

smaller, pinkish inner petals. A compound fruit, the cherimoya is

conical or somewhat heart-shaped, 4 to 8 in (10 to 20 cm) long and up

to 4 in (10 cm) in width, weighing on the average 5 1/2 to 18 oz

(150-500 g) but extra large specimens may weigh 6 lbs (2.7 kg) or more.

The skin, thin or thick, may be smooth with fingerprint like markings

or covered with conical or rounded protuberances. The fruit is easily

broken or cut open, exposing the snow-white, juicy flesh, of pleasing

aroma and delicious, subacid flavor; and containing numerous hard,

brown or black, beanlike, glossy seeds, 1/2 to 3/4 in (1.25 to 2 cm)

long.

Origin and Distribution

The

cherimoya is believed indigenous to the interandean valleys of Ecuador,

Colombia and Bolivia. In Bolivia, it flourishes best around Mizque and

Ayopaya, in the Department of Cochabamba, and around Luribay, Sapahaqui

and Rio Abajo in the Department of La Paz. Its cultivation must have

spread in ancient times to Chile and Brazil for it has become

naturalized in highlands throughout these countries. Many authors

include Peru as a center of origin but others assert that the fruit was

unknown in Peru until after seeds were sent by P. Bernabe Cobo from

Guatemala in 1629 and that thirteen years after this introduction the

cherimoya was observed in cultivation and sold in the markets of Lima.

The often-cited representations of the cherimoya on ancient Peruvian

pottery are actually images of the soursop, A. muricata L. Cobo

sent seeds to Mexico also in 1629. There it thrives between 4,000 and

5,000 ft (1312-1640 m) elevations.

It

is commonly grown and naturalized in temperate areas of Costa Rica and

other countries of Central America. In Argentina, the cherimoya is

mostly grown in the Province of Tucuman. In 1757, it was carried to

Spain where it remained a dooryard tree until the 1940's and 1950's

when it gained importance in the Province of Granada, in the Sierra

Nevada mountains, as a replacement for the many orange trees that

succumbed to disease and had to be taken out. By 1953, there were 262

acres (106 ha) of cherimoyas in this region.

In 1790 the

cherimoya was introduced into Hawaii by Don Francisco de Paulo Marin.

It is still casually grown in the islands and naturalized in dry upland

forests. In 1785, it reached Jamaica, where it is cultivated and occurs

as an escape on hillsides between 3,500 and 5,000 ft (1,066-1,524 m).

It found its way to Haiti sometime later. The first planting in Italy

was in 1797 and it became a favored crop in the Province of Reggio

Calabria. The tree has been tried several times in the Botanic Gardens,

Singapore first around 1878—but has always failed to survive

because of the tropical climate. In the Philippines, it does well in

the Mountain Province at an altitude above 2,460 ft (750 m). It was

introduced into India and Ceylon in 1880 and there is small-scale

culture in both countries at elevations between 1,500 and 7,000 ft

(457-2,134 m). The tree was planted in Madeira in 1897, then in the

Canary Islands, Algiers, Egypt and, probably via Italy, in Libya,

Eritrea and Somalia.

The United States Department of

Agriculture imported a number of lots of cherimoya seeds from Madeira

in 1907 (S.P.I. Nos. 19853, 19854, 19855, 19898, 19901, 19904, 19905).

Seeds

from Mexico were planted in California in 1871. There were 9,000 trees

in that state in 1936 but many of them were killed by a freeze in 1937.

Several small commercial orchards were established in the 1940's. At

present there may be less than 100 acres (42 ha) in the milder parts of

San Diego County. Seeds, seedlings and grafted trees from California

and elsewhere have been planted in Florida many times but none has done

well. Any fruits produced have been of poor quality.

Varieties

In Peru, cherimoyas are classed according to degree of surface

irregularity, as: 'Lisa',

almost smooth; 'Impresa',

with "fingerprint" depressions; 'Umbonada',

with rounded protrusions; 'Papilonado',

or 'Tetilado',

with fleshy, nipple-like protrusions; 'Tuberculada',

with conical protrusions having wartlike tips. At the Agricultural

Experiment Station "La Molina", several named and unnamed selections

collected in northern Peru are maintained and evaluated. Among the more

important are: #1, 'Chavez',

fruits up to 3.3 lbs (1 1/2 kg); February to May; #2, 'Names', fruits

January to April; #3, 'Sander',

fruits with moderate number of seeds; July and early August; #4, fruit

nearly smooth, not many seeds, 1.1 to 2.2 lbs (1/2-1 kg), June to

August; #5, nearly smooth, very sweet, 2.2 Ibs (1 kg), March to June;

#6, fruit with small protuberances, 1.1 to 2.2 Ibs (1/2-1 kg), not many

seeds; #7 fruit small, very sweet, many seeds, March to May; #8, fruit

very sweet, 1.1 to 2.2 Ibs (1/2 1 kg), with very few seeds, February to

April.

In the Department of Antioquia, Colombia, a cultivar called 'Rio Negro'

has heart shaped fruits weighing 1 3/4 to 2.2 Ibs (0.8-1 kg). The

cherimoyas of Mizque, Cochabamba, Bolivia, are locally famed for their

size and quality. 'Concha

Lisa' and 'Bronceada'

are grown commercially in Chile. Other cultivars mentioned in Chilean

literature are 'Concha

Picuda' and 'Terciopelo'.

Dr.

Ernesto Saavedra, University of Chile, after ex perimenting with growth

regulators for 4 years, developed a super cherimoya, 4 to 6 in (10-15

cm) wide and weighing up to 4 Ibs (1.8 kg); symmetrical, easy to peel

and seedless, hence having 25% more flesh than an ordinary cherimoya.

However, the larger fruits are subject to cracking.

The leading commercial cultivars in Spain are 'Pinchua'

(thin-skinned) and 'Baste'

(thick-skinned.)

Named cultivars in California include:

'Bays'—rounded,

fingerprinted, light green, medium to large, of excellent flavor; good

bearer; early.

'Whaley'—long-conical,

sometimes shouldered at the base, slightly and irregularly tuberculate,

with fairly thick, downy skin. Of good flavor, but membranous sac

around each seed may adhere to flesh. Bears well; grown commercially;

early.

'Deliciosa'—long-conical,

prominently papillate; skin thin, slightly downy; variable in flavor;

only fair in quality; generally bears well but doesn't ship well;

cold-resistant. Midseason.

'Booth'—short-conical,

fingerprinted, medium to large; of good flavor; next to 'Deliciosa in

hardiness. Late.

'McPherson'—short

conical, fingerprinted but umbonate at the base; medium to large; of

high quality; bears well. Midseason.

'Carter'—long-conical,

but not shouldered; smooth or faintly fingerprinted; skin green to

bronze; bears well. Late. Leaves wavy or twisted.

'Ryerson'—long-conical,

smooth or fingerprinted, with tbick, tough, green or yellow green skin;

of fair quality; ships well. Leaves wavy or twisted.

'White'—short-conical

with rounded apex; slightly papillate to umbonate; medium to large;

skin medium thick; of good flavor; doesn't bear well near the coast.

'Chaffey'—introduced

in 1940s; rounded, short, finger printed; of medium size; excellent

quality; bears well, even without hand-pollination.

'Ott'—(Patent

#656)—introduced in 1940's; long conical to heart shaped,

slightly tuberculate; of excellent flavor; ships well.

Among others that have been planted in California but considered

inferior are: 'Horton',

'Golden Russet',

'Loma', 'Mire Vista', 'Sallmon'.

Pollination

A

problem with the cherimoya is inadequate natural pollination because

the male and female structures of each flower do not mature

simultaneously. Few insects visit the flowers. Therefore,

hand-pollination is highly desirable and must be done in a 6- to 8-hour

period when the stigmas are white and sticky. It has been found in

Chile that in the first flowers to open the pollen grains are loaded

with starch, whereas flowers that open later have more abundant pollen,

no starch grains, and the pollen germinates readily. Partly-opened

flowers are collected in the afternoon and kept in a paper bag

overnight. The next morning the shed pollen is put, together with moist

paper, in a vial and transferred by brush to the receptive stigmas.

Usually only a few of the flowers on a tree are pollinated each time,

the operation being repeated every 4 or 5 days in order to extend the

season of ripening. The closely related A. senegalensis Pers., if

available, is a good source of abundant pollen for pollinating the

cherimoya. The pollen of the sugar apple is not satisfactory. Fruits

from hand-pollinated flowers will be superior in form and size.

Climate

The

cherimoya is subtropical or mild-temperate and does not succeed in the

lowland tropics. It requires long days. In Colombia and Ecuador, it

grows naturally at elevations between 4,600 and 6,600 ft (1,400-2,000

m) where the temperature ranges between 62.6° and 68°F

(17°-20°C). In Peru, the ideal climate for the

cherimoya is

said to lie between 64.5° and 77°F

(18°-25°C) in the

summer and 64.5° and 41°F (18°-5°C) in

winter. In

Guatemala, naturalized trees are common between 4,000 and 8,200 ft

(1,200-2,500 m) though the tree produces best between 4,000 and 5,900

ft (1,200-1,800 m) and can be grown at elevations as low as 2,950 ft

(900 m). The tree cannot survive the cold in the Valle de Mexico at

7,200 ft (2,195 m). In Argentina, young trees are wrapped with dry

grass or burlap during the winter. The cherimoya can tolerate light

frosts. Young trees can withstand a temperature of 26°F

(-3.33°C), but a few degrees lower will severely injure or kill

mature trees. In February 1949, a small scale commercial grower (B. E.

Needham) in Glendora, California, reported that most of his crop was

lost because of frost and snow, the cherimoya suffering more cold

damage than his avocados, oranges or lemons.

The tree prefers

a rather dry environment as in southern Guatemala where the rainfall is

50 in (127 cm) and there is a long dry season. It is not adaptable to

northern Guatemala where the 100 inch (254 cm) rainfall is spread

throughout the year.

Finally, the tree should be protected from strong winds which interfere

with pollination and fruit set.

Soil

The

cherimoya tree performs well on a wide range of soil types from light

to heavy, but seems to do best on a medium soil of moderate fertility.

In Argentina, it makes excellent growth on rockstrewn, loose, sandy

loam 2 to 3 ft (0.6-0.9 m) above a gravel subsoil. The optimum pH

ranges from 6.5 to 7.6. A greenhouse trial in sand has demonstrated

that the first nutritional deficiency evoked in such soil is lack of

calcium.

Propagation

Cherimoya

seeds, if kept dry, will remain viable for several years. While the

tree is traditionally grown from seed in Latin America, the tendency of

seedlings to produce inferior fruits has given impetus to vegetative

propagation.

Seeds for rootstocks are first soaked in water

for 1 to 4 days and those that float are discarded. Then planting is

done directly in the nursery row unless the soil is too cool, in which

case the seeds must be placed in sand peat seedbeds, covered with 1 in

(2.5 cm) of soil and kept in a greenhouse. They will germinate in 3 to

5 weeks and when the plants are 3 to 4 in (7.5-10 cm) high, they are

transplanted to pots or the nursery plot with 20 in (50 cm) between

rows. When 12 to 24 months old and dormant, they are budded or grafted

and then allowed to grow to 3 or 4 ft (0.9-1.2 m) high before setting

out in the field. Large seedlings and old trees can be topworked by

cleft-grafting. It is necessary to protect the trunk of topped trees to

avoid sunburn.

The cherimoya can also be grafted onto the custard apple (A. reticulata).

In India this rootstock has given 90% success. Cuttings of mature wood

of healthy cherimoya trees have rooted in coral sand with bottom heat

in 28 days.

Culture

The

young trees should be spaced 25 to 30 ft (7.5-9 m) apart each way in

pits 20 to 24 in (50-60 cm) wide, enriched with organic material. In

Colombia, corn (maize), vegetables, ornamental foliage plants, roses or

annual flowers for market are interplanted during the first few years.

In Spain, the trees are originally spaced 16.5 ft (5 m) apart with the

intention of later thinning them out. Thinning is not always done and

around the village of Jete, where the finest cherimoyas are produced,

the trees have grown so close together as to form a forest. In the

early years they are interplanted with corn, beans and potatoes.

Pruning

to eliminate low branches, providing a clean trunk up to 32 in (80 cm),

to improve form, and open up to sunlight and pesticide control, is done

preferably during dormancy. After 6 months, fertilizer (10-8-6 N, P, K)

is applied at the rate of 1/2 lb (227 g) per tree and again 6 months

later at 1 lb (454 g) per tree. In the 3rd year, the fertilizer formula

is changed to 6-10-8 N,P,K and each year thereafter the amount per tree

is increased by 1 lb (454 g) until the level of 5 lbs (2.27 kg) is

reached. Thenceforth this amount is continued each year per tree. The

fertilizer is applied in trenches 6 in (15 cm) deep and 8 in (20 cm)

wide dug around each tree at a distance of 5 ft (1.5 m) from the base,

at first; later, at an appropriately greater distance.

Young

trees are irrigated every 15 to 20 days for the first few years except

during the winter when they must be allowed to go

dormant—ideally

for 4 months. When the first leafbuds appear, irrigation is resumed.

With bearing trees, watering is discontinued as soon as the fruits are

full-grown.

In Chile, attempts to increase fruit set with

chemical growth regulators have been disappointing. Spraying flowers

with gibberellic acid has increased fruit set and improved form and

size but induces deep cracking prior to full maturity, far beyond the

normal rate of cracking in fruits from natural or hand-pollinated

flowers.

Cropping and Yield

The

cherimoya begins to bear when 3 1/2 to 5 years old and production

steadily increases from the 5th to the 10th year, when there should be

a yield of 25 fruits per tree—2,024 per acre (5,000 per ha).

Yields of individual trees have been reported by eyewitnesses as a

dozen, 85, or even 300 fruits annually. In Colombia, the average yield

is 25 fruits; as many as 80 is exceptional. In Italy, trees 30 to 35

years old produce 230 to 280 fruits annually.

The fruits must

be picked when full grown but still firm and just beginning to show a

slight hint of yellowish-green and perhaps a bronze cast. Bolivians

judge that a fruit is at full maturity by shaking it and listening for

the sound of loose seeds. Italians usually wait for the yellowish hue

and the sweet aroma noticeable at a distance, picking the fruits only

24 to 28 hours prior to consumption. However, if the fruits must travel

to markets in central Italy, they are harvested when the skin turns

from dark-green to lighter green.

In harvesting, the fruits

must be clipped from the branch so as to leave only a very short stem

attached to the fruit to avoid stem caused damage to the fruits in

handling, packing and shipping.

Keeping Quality and Storage

Firm

fruits should be held at a temperature of 50°F (10°C)

to retard

softening. When transferred to normal room temperature, they will

become soft and ready to eat in 3 to 4 days. Then they can be kept

chilled in the home refrigerator if not to be consumed immediately. A

California grower has shipped cherimoyas ('Deliciosa' and 'Booth')

packed in excelsior in 12 lb (5.5-kg) boxes to Boston and New York

quite satisfactorily. And the fruit has been shipped from Madeira to

London for many years.

In Bolivia, fruits for home use are

wrapped in woollen cloth as soon as picked and kept at room temperature

so that they can be eaten 3 days later.

Pests and Diseases

The

cherimoya tree is resistant to nematodes. Very few problems have been

noted in California except for infestations of mealybugs, especially at

the base of the fruit, and these can be flushed off. In Colombia, on

the other hand, it is said that a perfectly healthy tree is a rarity.

In the Valle de Tenza, formerly an important center of production, lack

of control of pests greatly reduced the plantations before 1960 when

programs were launched to improve cherimoya culture here and in various

other regions of the country.

Caterpillars (Thecla

sp. and Oiketicus kubeyi)

may defoliate the tree. A scale insect, Conchaspis angraeci

attacks the trunk and branches. Prime enemies are reported to be fruit

flies (Anastrepha

sp. ); leaf miners (Leucoptera

sp.), particularly in the Valle de Tenza, which necessitate the

collection and burning of affected leaves plus the application of

systemic insecticides; and the seed borer (Bephrata maculicollis).

The latter pest deposits eggs on the surface of the developing fruits,

the larvae invade the fruit and consume the seeds, causing premature

and defective ripening and rendering the fruits susceptible to fungal

diseases. This pest is difficult to combat. Borers attack the tree in

Argentina reducing its life span from 60 to 30 years.

The coccid, Pseudococcus

filamentosus attacks the fruit in Hawaii, and Aulacaspis miranda

and Ceropute yuccae in Mexico. In Spain, the thin-skinned cultivar

'Pinchua' is subject to attack by the Mediterranean fruit-fly, Ceratitis capitata.

Stored

seeds for planting are subject to attack by weevils. To avoid

damping-off of young seedlings, dusting of seeds with fungicide is

recommended. The tree may succumb to root-rot in clay soils or where

there is too much moisture and insufficient drainage. Sooty mold may

occur on leaves and fruits where ants, aphids and other insects have

deposited honeydew.

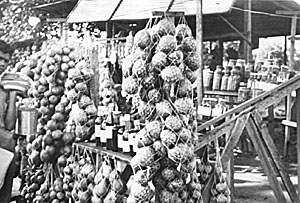

Fig. 19: Cherimoyas (Annona

cherimola) from the highlands are sold at fruit stands

along Venezuelan roadways.

Food Uses

The

flesh of the ripe cherimoya is most commonly eaten out of-hand or

scooped with a spoon from the cut open fruit. It really needs no

embellishment but some people in Mexico like to add a few drops of lime

juice. Occasionally it is seeded and added to fruit salads or used for

making sherbet or ice cream. Colombians strain out the juice, add a

slice of lemon and dilute with ice-water to make a refreshing soft

drink. The fruit has been fermented to produce an alcoholic beverage.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion |

Analysis

of cherimoyas in Ecuador

|

| Colombian

Analysis

|

| Moisture |

74.6

g |

| Moisture |

77.1

g |

| Ether

Extract |

0.45

g |

| Protein |

1.9

g |

| Crude

Fiber |

1.5

g |

| Fat |

0.1

g |

| Nitrogen |

.227

g |

| Carbohydrates |

18.2

g |

| Ash |

0.61

g |

| Fiber |

2.0

g |

| Calcium |

21.7

g |

| Ash |

0.7

g |

| Phosphorus |

30.2

mg |

| Calcium |

32.0

mg |

| Iron |

0.80

mg |

| Phosphorus |

37.0

mg |

| Carotene |

0.000

mg |

| Iron |

0.5

mg |

| Thiamine |

0.117

mg |

| Vitamin

A (Carotene) |

0.0

I.U. |

| Riboflavin |

0.112

mg |

| Thiamine |

0.10

mg |

| Niacin |

1.02

mg |

| Riboflavin |

0.14

mg |

| Ascorbic

Acid |

16.8

mg |

| Niacin |

0.9

mg |

|

|

| Ascorbic

Acid |

5.0

mg |

|

Toxicity

The

seeds, like those of other Annona species, are crushed and used as

insecticide. Paul Allen, in his Poisonous and Injurious Plants of

Panama, (see Bibliography), implies personal knowledge of a case of

blindness resulting from "the juice of the crushed seeds coming in

contact with the eyes. "The seeds contain several alkaloids: caffeine,

( + )-reticuline, (-)-anonaine, liriodenine, and lanuginosine.

Human

ingestion of 0.15 g of the dark-yellow resin isolated from the seeds

produces dilated pupils, intense photophobia, vomiting, nausea, dryness

of the mouth, burning in the throat, flatulence, and other symptoms

resembling the effects of atropine. A dose of 0.5 g, injected into a

medium-sized dog, caused profuse vomiting.

Wilson Popenoe

wrote that hogs feed on the fallen fruits in southern Ecuador where

there are many cherimoya trees and few people. One wonders whether the

hogs swallow the hard seeds whole and avoid injury.

The twigs

possess the same alkaloids as the seeds plus michelalbine. A team of

pharmacognosists in Spain and France has reported 8 alkaloids in the

leaves: ( + )-isoboldine, (-)-stepholidine, ( + )-corytuberine, ( + )

nornantenine, ( + )-reticuline, (-)-anonaine, liriodenine, and lanuginosine.

Other Uses

In Jamaica, the dried flowers have been used as flavoring for snuff.

Medicinal Uses:

In Mexico, rural people toast, peel and pulverize 1 or 2 seeds and take

the powder with water or milk as a potent emetic and cathartic. Mixed

with grease, the powder is used to kill lice and is applied on

parasitic skin disorders. A decoction of the skin of the fruit is taken

to relieve pneumonia.

|

|