Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Psidium guajava L.

Local Names: Amharic (zeituna);

Arabic (juafa, juava, guwâfah); Bengali (goaachhi, piyara, peyara);

Burmese (malakapen); Creole Patois (gwayav); Dutch (goejaba); English

(common guava, guava); Filipino (bayabas, guyabas); French

(goyava, goyavier); German (Guavenbaum, guava); Hawaian (kuawa); Hindi

(goaachhi, jamba, amrud, amarood, sapari, safed safari); Indonesian (jambu

biji); Japanese (banjiro); Javanese (jambu klutuk); Khmer (trapaek

sruk); Lao (Sino-Tibetan) (si da); Luganda (mupeera); Malay (jambu

berase, jambu biji, jambu kampuchia, jambu batu); Mandinka (biabo);

Portuguese (goiaba); Sanskrit (mansala); Sinhala (koiya, pera); Spanish

(araza-puita, gauyaba blanca, perulera, guaiaba dulce, guayaba, Guayaba

agria, guayaba común, guayabillo, agria); Swahili (mpera); Tamil

(koyya); Thai (ma-man, farang, ma-kuai); Tigrigna (zeitun); Urdu (amrud);

Vietnamese (oi)

Family: Myrtaceae

Botanic Description

Psidium guajava is a

large dicotyledonous shrub, or small evergreen tree, generally 3-10 m

high, many branches; stems crooked, bark light to reddish brown, thin,

smooth, continuously flaking; root system generally superficial and

very extensive, frequently extending well beyond the canopy, there are

some deep roots but no distinct taproot.

Leaves opposite,

simple; stipules absent, petiole short, 3-10 mm long; blade oblong to

elliptic, 5-15 x 4-6 cm, apex obtuse to bluntly acuminate, base rounded

to subcuneate, margins entire, somewhat thick and leathery, dull grey

to yellow-green above, slightly downy below, veins prominent, gland

dotted.

Inflorescence, axillary, 1- to 3-flowered, pedicles

about 2 cm long, bracts 2, linear. Calyx splitting irregularly into 2-4

lobes, whitish and sparsely hairy within; petals 4-5, white,

linear-ovate c. 2 cm long, delicate; stamens numerous, filaments pale

white, about 12 mm long, erect or spreading, anther straw coloured;

ovary inferior, ovules numerous, style about 10 cm long, stigma green,

capitate.

Fruit an ovoid or pear-shaped berry, 4-12 cm long,

weighing up to 500 g; skin yellow when ripe, sometimes flushed with

red; pulp juicy, creamy-white or creamy-yellow to pink or red; mesocarp

thick, edible, the soft pulp enveloping numerous, cream to brown,

kidney-shaped or flattened seeds. The exterior of the fruit is fleshy,

and the centre consists of a seedy pulp.

From the Greek psidion (pomegranate), due to a fancied resemblance between the two fruits.

Biology

The

pollen is viable for up to 42 hours and the stigmas are receptive for

about 2 days. Bees are the principal pollinators. There is some self-

and cross-incompatibility but several cultivars have set fair crops of

seedless or few-seeded fruit. Levels of 60-75% selfing have been found

in natural populations; this has been used to produce homozygotic

varieties that can be propagated from seed. It is not known to what

extent erratic flowering through the year affects pollination

intensity. One of the most critical botanical characteristics of guava

is that flowers are borne on newly emerging lateral shoots,

irrespective of the time of year. The floral structure, which makes

emasculation difficult and with a juvenile period of 3-5 years limit

conventional breeding.

Seedlings may flower within 2 years;

clonally propagated trees often begin to bear during the first year

after planting. Trees reach full bearing after 5- 8 years, depending on

growing conditions and spacing. The guava is not a long-lived tree

(about 40 years), but the plants may bear heavily for 15-25 years. Bats

are the main fruit dispersal agents.

Ecology

P. guajava

appears to have evolved in relatively open areas, such as

savannah/shrub transitional zones, or in frequently disturbed areas

where it is a strong competitor in early secondary growth. In some

areas it is found in large thickets with as many as 100 plants in an

area of less than half a hectare, although it is more often found in

densities of 1-5 plants/ha. P. guajava

is considered a noxious weed in many tropical pasture lands (when

chemical control is not available, guava proliferation may result in

the abandonment of a pasture). The guava is a hardy tree that adapts to

a wide range of growing conditions. It can stand a wide range of

temperatures; the highest yields are recorded at mean temperatures of

23-28 deg. C. In the subtropics quiescent trees withstand light frost

and 3.5-6 months (depending on the cultivar) of mean temperatures above

16 deg. C suffice for flowering and fruiting. It fruits at altitudes up

to 1 500 m and survives up to 2 000 m. Guava is more drought-resistant

than most tropical fruit crops. For maximum production in the tropics,

however it requires rainfall distributed over the year. If fruit ripens

during a very wet period it loses flavour and may split.

Biophysical Limits

Altitude: 0-2 000 m, Mean annual temperature: 15-45 deg. C, Mean annual rainfall: 1 000-2 000 mm

Soil

type: Soils vary widely, including slightly to strongly acid. As

expected from a secondary colonizer, it grows well on poor soils with

reasonably good drainage, however growth and production are better on

rich clay loams.

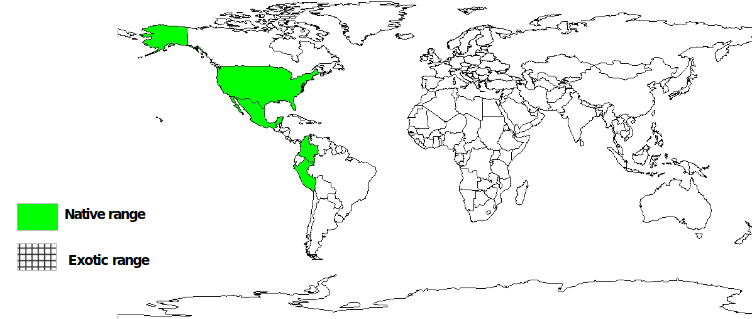

Documented Species Distribution

Native: Colombia, Mexico, Peru, United States of America

Exotic:

Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Costa Rica,

Cote d'Ivoire, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia,

Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Greece, Guyana, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Israel,

Kenya, Laos, Malawi, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama,

Philippines, Puerto Rico, Samoa, Senegal, South Africa, Sri Lanka,

Sudan, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Uganda, Venezuela, Vietnam

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food:

The whole fruit is edible; flavour varies from very acid to sweet with

the best fruit being both sweet and mildly acid. It has a pleasant

aroma, is very high in vitamin C (10-2 000 mg/100 g of fruit), and a

rich source of vitamin A and pectin (0.1-1.8%). Pectin content

increases during ripening and declines rapidly in over-ripe fruit.

Table varieties with good taste, large size and high pulp to seed

ratio, have been developed for the fresh fruit market in many

countries. Other varieties have been developed for the industrial

purposes and the following wide variety of products are available:

canned fruit or mesocarps in sweet syrup, puree, goiabada (a type of

thick, sweet jam), jams and jellies, juices and nectars, ice cream and

yoghurts. Guava paste, or guava cheese as known in the West Indies, is

made by evaporating the pulp with sugar; it is eaten as a sweetmeat. A

firm in the Philippines dehydrates slices of the outer, non-seeded part

of the fruit to make a similar product. In some Asian countries such as

Indonesia, the leaves are used in cooking.

Apiculture:

White fragrant flowers secrete nectar in excess all day attracting

bees, which also collect juice from the damaged fruits. In India for

instance, the blossoms occur in May and June.

Fuel:

Wood makes excellent firewood and charcoal because of its abundance,

natural propagation, and classification as an undesirable weed.

Timber:

Sapwood light brown, heartwood brown or reddish; hard, moderately

strong and durable. It is used for tool handle, fence posts and in

carpentry and turnery.

Tannin or dyestuff: The leaves and bark may be used for dyeing and tanning.

Essential oil: Plant contains an essential oil. The volatile oil with methylchavicol, persein and d-pinene (a paraffin) is found in the leaf.

Alcohol: Winemaking from the fruit has been commercialized in southern Africa.

Poison: P. guajava has insecticidal properties.

Medicine:

All parts of the young fruit are astringent. Guava exhibits

antibacterial action against intestinal pathogens such as

Staphyloccocus. The dried ripe fruits are recommended as a remedy for

dysentery, while the leaves and fruits are used as a cure for

diarrhoea. Oil contains bisabolene and flavinoides that exhibit

anti-inflammatory properties. A decoction of the leaves or bark is

taken externally as a lotion for skin complaints, ringworm, wounds, and

ulcers. Water from soaking the fruit is good to treat diabetes. The

leaves are made into a cataplasm; cooked, they are given to horses with

strangle.

Some suggested treatments are digestive tract ailments,

cold, and high blood pressure: leaf decoction or fruit juice with salt

or sugar taken orally. Trauma, pain, headache, and rheumatism: hot leaf

decoction compress. Sore throat, hoarse throat: leaf decoction, gargle.

Varix, ulcer: leaf decoction, treated with warm water, bath. Hepatitis,

gonorrhoea, and diarrhoea: clear fruit juice.

Services

Ornamental: Widely cultivated as an ornamental fruit tree.

Boundary or barrier or support: P. guajava has been used to stake yams (Dioscorea spp.); the small tree is cut back and used to support them. Yield increases of 33-85% have been recorded in Nigeria.

Intercropping:

Performed very well when intercropped with fodder crops such as maize,

sorghum and cowpeas. Tree growth reduction is very small. Pollution

control: Identified as useful for bio-indication and as a

bio-accumulator in India. It is sensitive to sulphur dioxide;

sensitivity to injury based on chlorophyll destruction.

Tree Management

For

intensively managed orchards in Thailand trees are spaced only 4-6 m

apart but seedlings for fruit processing may be spaced up to 10 x 8 m

apart. Irrigation during the dry season and frequent light pruning to

promote the emergence of flowering shoots are employed for continuity

of production throughout the year. When the crop is cycled most

fertilizer is applied as a basal dressing at the end of the harvest, if

necessary supplemented by a top dressing; if trees are cropped

continuously, fertilizers are applied in several small doses. Growth

rate is excellent and the plants coppice readily. Branching is

extensive and pruning is necessary to form good orchard trees. Firewood

cuttings cause excessive propagation by formulation of sprouts and

suckers.

Best time of day to harvest is early morning because by

noon fruit is warmer and deteriorates more rapidly. During harvesting,

great care is necessary to avoid fruit damage, as when collected almost

ripe, they will only store for about 2- 3 days at room temperature.

Fruit for industrial purposes do not need such care but greater speed

is still essential. Average yields are between 30-40 kg/plant in 5

year-old plants and will reach a maximum production of 50-70 kg at

about 7 years if well managed.

Germplasm Management

Seed

storage behaviour is orthodox; seeds at 6% mc survive 24 hours in

liquid nitrogen; no loss in viability following 66 months hermetic

storage at -20 deg. C with 5.5% mc.

Pests and Diseases

Insect pests are numerous and in some cases severe. Fruit fly maggots such as Anastrepha striata, Dacus spp. and Ceratitis spp. are especially troublesome. Aphids (Aphis spp.) feed on young growth, causing the curling of leaves. Selenothirps rubrocinctus,

the red-banded thirp; adult and larval forms puncture leaves of the

infested tree and brownish stains appear. Heavily infested trees are

sometimes completely defoliated.

In Brazil yellow rust (Puccina psidii) is an extremely serious fungal pest, as are leaf spot (Phyllosticha guajayae) and anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides). The green scale (Coccus viridis) occurs on branches. Fruit rot (Glomerella cingulata) shrivels green fruit and rots ripe fruit. Mushroom root rot (Clitocybe tabescens) can eventually kill the tree.

Further Reading

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Beg MU et. al. 1990. Performance of trees around a thermal power station. Environment and Ecology. 8(3): 791-797.

Bein E. 1996. Useful trees and shrubs in Eritrea. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Nairobi, Kenya.

Bekele-Tesemma

A, Birnie A, Tengnas B. 1993. Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia.

Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International

Development Authority (SIDA).

Coates-Palgrave K. 1988. Trees of southern Africa. C.S. Struik Publishers Cape Town.

Cobley L.S & Steele W.M. 1976. An Introduction to the Botany of Tropical Crops. Longman Group Limited.

El Amin HM. 1990. Trees and shrubs of the Sudan. Ithaca Press, Exeter.

FAO. 1983. Food and fruit bearing forest species. 3: Examples from Latin America. FAO Forestry Paper. 44/3. Rome.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

ICRAF.

1992. A selection of useful trees and shrubs for Kenya: Notes on their

identification, propagation and management for use by farming and

pastoral communities. ICRAF.

Katende AB et al. 1995. Useful trees

and shrubs for Uganda. Identification, Propagation and Management for

Agricultural and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit

(RSCU), Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Lanzara P. and Pizzetti M. 1978. Simon & Schuster's Guide to Trees. New York: Simon and Schuster

Little EL. 1983. Common fuelwood crops. Communi-Tech Association, Morgantown, West Virginia.

Mbuya

LP et al. 1994. Useful trees and shrubs for Tanzania: Identification,

Propagation and Management for Agricultural and Pastoral Communities.

Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International

Development Authority (SIDA).

Nicholson B.E, Harrison S.G, Masefield G.B & Wallis M. 1969. The Oxford Book of Food Plants. Oxford University Press.

Noad T, Birnie A. 1989. Trees of Kenya. General Printers, Nairobi.

Perry LM. 1980. Medicinal plants of East and South East Asia : attributed properties and uses. MIT Press. South East Asia.

Peter G von Carlowitz.1991. Multipurpose Trees and Shrubs-Sources of Seeds and Innoculants. ICRAF. Nairobi, Kenya

Raynor B. 1991. Agroforestry systems in Pohnpei. Practices and strategies for development. Forestry Development Programme.

Sardar Singh. 1975. Bee-keeping in India. Indian Council for Agricultural Research.

Sedgley M, Griffin AR. 1989. Sexual reproduction of tree crops. Academic Press. London.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Vogt K.

1995. A field guide to the identification, propagation and uses of

common trees and shrubs of dryland Sudan. SOS Sahel International (UK).

Williams R.O & OBE. 1949. The useful and ornamental plants in Zanzibar and Pemba. Zanzibar Protectorate.

|

|