From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Jambolan

Syzygium cumini Skeels

Syzygium jambolanum DC.

Eugenia cumini Druce

This member of the Myrtaceae is of wider interest for its medicinal applications than for its edible fruit. Botanically it is Syzygium cumini Skeels (syns. S. jambolanum DC., Eugenia cumini Druce, E. jambolana Lam., E. djouat Perr., Myrtus cumini L., Calyptranthes jambolana

Willd.). Among its many colloquial names are Java plum, Portuguese

plum, Malabar plum, black plum, purple plum, and, in Jamaica, damson

plum; also Indian blackberry. In India and Malaya it is variously known

as jaman, jambu, jambul, jambool, jambhool, jamelong, jamelongue,

jamblang, jiwat, salam, or koriang. In Thailand, it is wa, or ma-ha; in

Laos, va; Cambodia, pring bai or pring das krebey; in Vietnam, voi

rung; in the Philippines, duhat, lomboy, lunaboy or other dialectal

appelations; in Java, djoowet, or doowet. In Venezuela, local names are

pésjua extranjera or guayabo pésjua; in Surinam, koeli,

jamoen, or druif (Dutch for "grape"); in Brazil, jambuláo,

jaláo, jameláo or jambol

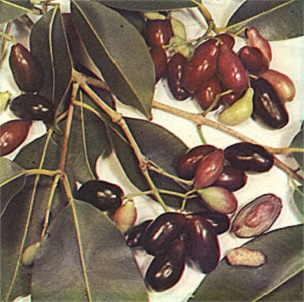

Plate LII: JAMBOLAN, Syzygium cumini

Description

The

jambolan is fast-growing, reaching full size in 40 years. It ranges up

to 100 ft (30 m) in India and Oceania; up to 40 or 50 ft (12-15 m) in

Florida; and it may attain a spread of 36 ft (11 m) and a trunk

diameter of 2 or 3 ft (0.6-0.9 m). It usually forks into multiple

trunks a short distance from the ground. The bark on the lower part of

the tree is rough, cracked, flaking and discolored; further up it is

smooth and light-gray. The turpentine-scented evergreen leaves are

opposite, 2 to 10 in (5-25 cm) long, 1 to 4 in (2.5-10 cm) wide;

oblong-oval or elliptic, blunt or tapering to a point at the apex;

pinkish when young; when mature, leathery, glossy, dark-green above,

lighter beneath, with conspicuous, yellowish midrib. The fragrant

flowers, in 1-to 4-in (2.5-10 cm) clusters, are 1/2 in (1.25 cm) wide,

1 in (2.5 cm) or more in length; have a funnel-shaped calyx and 4 to 5

united petals, white at first, then rose-pink, quickly shed leaving

only the numerous stamens.

The fruit, in clusters of just a few

or 10 to 40, is round or oblong, often curved; 1/2 to 2 in (1.25-5 m)

long, and usually turns from green to light-magenta, then dark-purple

or nearly black as it ripens. A white-fruited form has been reported in

Indonesia. The skin is thin, smooth, glossy, and adherent. The pulp is

purple or white, very juicy, and normally encloses a single, oblong,

green or brown seed, up to 1 1/2 in (4 cm) in length, though some

fruits have 2 to 5 seeds tightly compressed within a leathery coat, and

some are seedless. The fruit is usually astringent, sometimes

unpalatably so, and the flavor varies from acid to fairly sweet.

Origin and Distribution

The

jambolan is native in India, Burma, Ceylon and the Andaman Islands. It

was long ago introduced into and became naturalized in Malaya. In

southern Asia, the tree is venerated by Buddhists, and it is commonly

planted near Hindu temples because it is considered sacred to Krishna.

The leaves and fruits are employed in worshipping the elephant-headed

god, Ganesha or Vinaijaka, the personification of "Pravana" or "Om",

the apex of Hindu religion and philosophy.

The tree is thought

to be of prehistoric introduction into the Philippines where it is

widely planted and naturalized, as it is in Java and elsewhere in the

East Indies, and in Queensland and New South Wales, also on the islands

of Zanzibar and Pemba and Mombasa and adjacent coast of Kenya. In

Ghana, it is found only in gardens. Introduced into Israel perhaps

about 1940, it grows vigorously there but bears scantily, the fruit is

considered valueless but the tree is valued as an ornamental and for

forestry in humid zones. It is grown to some extent in Algiers.

By

1870, it had become established in Hawaii and, because of seed

dispersal by mynah birds, it occurs in a semiwild state on all the

Hawaiian islands in moist areas below 2,000 ft (600 in). There are

vigorous efforts to exterminate it with herbicides because it shades

out desirable forage plants. It is planted in most of the inhabited

valleys in the Marquesas. It was in cultivation in Bermuda, Cuba,

Haiti, Jamaica, the French Islands of the Lesser Antilles and Trinidad

in the early 20th Century; was introduced into Puerto Rico in 1920; but

still has remained little-known in the Caribbean region. At the

Lancetilla Experimental Garden at Tela, Honduras, it grows and fruits

well. It is seldom planted elsewhere in tropical America but is

occasionally seen in Guatemala, Belize, Surinam, Venezuela and Brazil.

The

Bureau of Plant Industry of the United States Department of Agriculture

received jambolan seeds from the Philippines in 1911, from Java in

1912, from Zanzibar and again from the Philippines in 1920. The tree

flourishes in California, especially in the vicinity of Santa Barbara,

though the climate is not congenial for production or ripening of

fruit. In southern Florida, the tree was rather commonly planted in the

past. Here, as in Hawaii, fruiting is heavy, only a small amount of the

crop has been utilized in home preserving. The jambolan has lost

popularity, as it has in Malaya where it used to be frequently grown in

gardens. Heavy crops litter streets, sidewalks and lawns, attracting

insects, rapidly fermenting and creating a foul atmosphere. People are

eager to have the trees cut down. Where conditions favor spontaneous

growth, the seedlings become a nuisance, as well.

Varieties

The

common types of jambolan in India are: 1) Ra Jaman, with large, oblong

fruits, dark-purple or bluish, with pink, sweet pulp and small seeds;

2) Kaatha, with small, acid fruits. Among named cultivars are, mainly, 'Early Wild', 'Late Wild', 'Pharenda'; and, secondarily, 'Small Jaman' and 'Dabka'

('Dubaka'). In Java, the small form is called Djoowet kreekil; a

seedless form is Djoowet booten. In southern Malaya, the trees are

small-leaved with small flower clusters. Farther north, the variety

called 'Krian Duat' has larger, thicker leaves and red inner bark. Fruits with purple flesh are more astringent than the white-fleshed types.

Climate

The

jambolan tree grows well from sea-level to 6,000 ft (1,800 m) but,

above 2,000 ft (600 m) it does not fruit but can be grown for its

timber. It develops most luxuriantly in regions of heavy rainfall, as

much as 400 in (1,000 cm) annually. It prospers on river banks and has

been known to withstand prolonged flooding. Yet it is tolerant of

drought after it has made some growth. Dry weather is desirable during

the flowering and fruiting periods. It is sensitive to frost when young

but mature trees have been undamaged by brief below-freezing

temperatures in southern Florida.

Soil

Despite

its ability to thrive in low, wet areas, the tree does well on higher,

well-drained land whether it be in loam, marl, sand or oolitic

limestone.

Propagation

Jambolan

seeds lose viability quickly. They are the most common means of

dissemination, are sown during the rainy season in India, and germinate

in approximately 2 weeks. Semi-hardwood cuttings, treated with

growth-promoting hormones have given 20% success and have grown well.

Budding onto seedlings of the same species has also been successful.

Veneer-grafting of scions from the spring flush has yielded 31%

survivors. The modified Forkert method of budding may be more feasible.

When a small-fruited, seedless variety in the Philippines was budded

onto a seeded stock, the scion produced large fruits, some with seeds

and some without. Approach-grafting and inarching are also practiced in

India. Air-layers treated with 500 ppm indolebutyric acid have rooted

well in the spring (60% of them) but have died in containers in the

summer.

Culture

Seedlings

grow slowly the first year, rapidly thereafter, and may reach 12 ft

(3.65 m) in 2 years, and begin bearing in 8 to 10 years. Grafted trees

bear in 4 to 7 years. No particular cultural attention seems to be

required, apart from frost protection when young and control measures

for insect infestations. In India, organic fertilizer is applied after

harvest but withheld in advance of flowering and fruiting to assure a

good crop. If a tree does not bear heavily, it may be girdled or

root-pruned to slow down vegetative growth.

The tree is grown as

shade for coffee in India. It is wind-resistant and sometimes is

closely planted in rows as a windbreak. If topped regularly, such

plantings form a dense, massive hedge. Trees are set 20 ft (6 m) apart

in a windbreak; 40 ft (12 m) apart along roadsides and avenues.

Fruiting Season

The

fruit is in season in the Marquesas in April; in the Philippines, from

mid-May to mid-June. In Hawaii, the crop ripens in late summer and

fall. Flowering occurs in Java in July and August and the fruits ripen

in September and October. In Ceylon, the tree blooms from May to August

and the fruit is harvested in November and December. The main fruiting

season in India and southern Florida (where the tree blooms principally

in February and March) extends through late May, June and July. Small

second crops from late blooms have been observed in October. Individual

trees may habitually bear later than others.

Harvesting and Yield

In

India, the fruits are harvested by hand as they ripen and this requires

several pickings over the season. Indian horticulturists have reported

a crop of 700 fruits from a 5-year-old tree. The production of a large

tree may be overwhelming to the average homeowner.

Pests and Diseases

In Florida, some jambolan trees are very susceptible to scale insects. The whitefly, Dialeurodes eugeniae,

is common on jambolans throughout India. Of several insect enemies in

South India, the most troublesome are leaf-eating caterpillars: Carea subtilis, Chrysocraspeda olearia, Phlegetonia delatrbc, 0enospila flavifuscata, Metanastria hyrtaca, and Euproctis fraterna. These pests may cause total defoliation. The leafminer, Acrocercops phaeospora, may be a major problem at times. Idiocerus atkinsoni sucks the sap of flowering shoots, buds and flower clusters, causing them to fall.

The fruits are attacked by fruit flies (Dacus diversus

in India), and are avidly eaten by birds and four-footed animals

(jackals and civets). In Australia, they are a favorite food of the

large bat called "flying fox."

Diseases recorded as found on the jambolan by inspectors of the Florida Department of Agriculture are: black leaf spot (Asterinella puiggarii); green scurf or algal leaf spot (Cephaleuros virescens); mushroom root rot (Clitocybe tabescens); anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides); and leaf spot caused by Phyllosticta eugeniae.

Food Uses

Jambolans

of good size and quality, having a sweet or subacid flavor and a

minimum of astringency, are eaten raw and may be made into tarts,

sauces and jam. Astringent fruits are improved in palatability by

soaking them in salt water or pricking them, rubbing them with a little

salt, and letting them stand for an hour. All but decidedly inferior

fruits have been utilized for juice which is much like grape juice.

When extracting juice from cooked jambolans, it is recommended that it

be allowed to drain out without squeezing the fruit and it will thus be

less astringent. The white-fleshed jambolan has adequate pectin and

makes a very stiff jelly unless cooking is brief. The more common

purple-fleshed yields richly colored jelly but is deficient in pectin

and requires the addition of a commercial jelling agent or must be

combined with pectinrich fruits such as unripe or sour guavas, or

ketembillas.

Good quality jambolan juice is excellent for

sherbet, sirup and "squash". In India, the latter is a bottled drink

prepared by cooking the crushed fruits, pressing out the juice,

combining it with sugar and water and adding citric acid and sodium

benzoate as a preservative.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Moisture | 83.7-85.8 g | | Protein | 0.7-0.129 g | | Fat | 0.15-0.3 g | | Crude Fiber | 0.3-0.9 g | | Carbohydrates | 14.0 g | | Ash | 0.32-0.4 g | | Calcium | 8.3-15 mg | | Magnesium | 35 mg | | Phosphorus | 15-16.2 mg | | Iron | 1.2-1.62 mg | | Sodium | 26.2 mg | | Potassium | 55 mg | | Copper | 0.23 mg | | Sulfur | 13 mg | | Chlorine | 8 mg | | Vitamin A | 8 I.U. | | Thiamine | 0.008-0.03 mg | | Riboflavin | 0.009-0.01 mg | | Niacin | 0.2-0.29 mg | | Ascorbic Acid | 5.7-18 mg | | Choline | 7 mg | | Folic Acid | 3 mcg |

*Values reported from Asian and tropical American analyses. |

|

Also present are gallic acid and tannin and a trace of oxalic acid.

In

Goa and the Philippines, jambolans are an important source of wine,

somewhat like Port, and the distilled liquors, brandy and "jambava"

have also been made from the fermented fruit. Jambolan vinegar,

extensively made throughout India, is an attractive, clear purple, with

a pleasant aroma and mild flavor.

Virmani gives the following

vinegar analysis: specific gravity, 1.0184; total acidity (as acetic

acid), 5.33 per 100 cc; volatile acid (as ascetic acid), 5.072 per 100

cc; fixed acidity, as citric, .275%; total solids, 4.12 per 100 cc;

ash, .42; alkalinity of ash, 32.5 (N/10 alkali); nitrogen, .6613 1;

total sugars, .995; reducing sugars, .995; non-volatile reducing

sugars, .995; alcohol, .159% by weight; oxidation value, (K MnO1),

186.4; iodine value, 183.7; ester value, 40.42.

Other Uses

Nectar:

The jambolan tree is of real value in apiculture. The flowers have

abundant nectar and are visited by bees (Apis dorsata) throughout the

day, furnishing most of the honey in the Western Ghats at an elevation

of 4,500 ft (1,370 m) where the annual rainfall is 300 to 400 in

(750-1,000 cm). The honey is of fine quality but ferments in a few

months unless treated.

Leaves:

The leaves have served as fodder for livestock and as food for tassar

silkworms in India. In Zanzibar and Pemba, the natives use young

jambolan shoots for cleaning their teeth. Analyses of the leaves show:

crude protein, 9.1%; fat, 4.3%; crude fiber, 17.0%; ash, 6.0%; calcium,

1.3%; phosphorus, 0.19%. They are rich in tannin and contain the

enzymes esterase and galloyl carboxylase which are presumed to be

active in the biosynthesis of the tannins.

The essential oil

distilled from the leaves is used to scent soap and is blended with

other materials in making inexpensive perfume. Its chemical composition

has been reported by Craveiro et al. in Brazil. It consists mainly of

mono- or sesqui-terpene hydrocarbons which are "very common in

essential oils."

Bark:

Jambolan bark yields durable brown dyes of various shades depending on

the mordant and the strength of the extract. The bark contains 8 to 19%

tannin and is much used in tanning leather and preserving fishing nets.

Wood:

The wood is red, reddish-gray or brownish-gray, with close, straight

grain. The very small, oval pores are often connected by waxy belts of

loose tissue. The medullary rays are so fine as to be clearly visible

only when greatly magnified. When fresh, the sapwood is attacked by

powerpost beetles, pinhole borers and ambrosia beetles. Both sapwood

and heartwood are perforated by the borer, Aeolesthes holosericea, if

the bark is left on for as long as 10 months. Air-dried wood is apt to

crack and split. When kiln dried, the heartwood is hard, difficult to

work but polishes well. It is durable in water and resistant to borers

and termites; tends to warp slightly. In India, it is commonly used for

beams and rafters, posts, bridges, boats, oars, masts, troughs,

well-lining, agricultural implements, carts, solid cart wheels, railway

sleepers and the bottoms of railroad cars. It is sometimes made into

furniture but has no special virtues to recommend it for cabinetwork.

It is a fairly satisfactory fuel.

Medicinal

Uses

The

jambolan has received far more recognition in folk medicine and in the

pharmaceutical trade than in any other field. Medicinally, the fruit is

stated to be astringent, stomachic, carminative, antiscorbutic and

diuretic. Cooked to a thick jam, it is eaten to allay acute diarrhea.

The juice of the ripe fruit, or a decoction of the fruit, or jambolan

vinegar, may be administered in India in cases of enlargement of the

spleen, chronic diarrhea and urine retention. Water-diluted juice is

used as a gargle for sore throat and as a lotion for ringworm of the

scalp.

The seeds, marketed in 1/4 inch (7 mm) lengths, and the

bark are much used in tropical medicine and are shipped from India,

Malaya and Polynesia, and, to a small extent, from the West Indies, to

pharmaceutical supply houses in Europe and England. Extracts of both,

but especially the seeds, in liquid or powdered form, are freely given

orally, 2 to 3 times a day, to patients with diabetes mellitus or

glycosuiria. In many cases, the blood sugar level reportedly is quickly

reduced and there are no ill effects. However, in some quarters, the

hypoglycemic value of jambolan extracts is disclaimed. Mercier, in

1940, found that the aqueous extract of the seeds, injected into dogs,

lowered the blood sugar for long periods, but did not do so when given

orally. Reduction of blood sugar was obtained in alloxan diabetes in

rabbits. In experiments at the Central Drug Research Institute,

Lucknow, the dried alcoholic extract of jambolan seeds, given orally,

reduced blood sugar and glycosuria in patients.

The seeds are

claimed by some to contain an alkaloid, jambosine, and a glycoside,

jambolin or antimellin, which halts the diastatic conversion of starch

into sugar. The seed extract has lowered blood pressure by 34.6% and

this action is attributed to the ellagic acid content. This and 34

other polyphenols in the seeds and bark have been isolated and

identified by Bhatia and Bajaj.

Other reported constituents of

the seeds are: protein, 6.3-8.5%; fat, 1.18%; crude fiber, 16.9%; ash,

21.72%; calcium, 0.41%; phosphorus, 0.17%; fatty acids (palmitic,

stearic, oleic and linoleic); starch, 41%; dextrin, 6.1%; a trace of

phytosterol; and 6 to 19% tannin.

The leaves, steeped in

alcohol, are prescribed in diabetes. The leaf juice is effective in the

treatment of dysentery, either alone or in combination with the juice

of mango or emblic leaves. Jambolan leaves may be helpful as poultices

on skin diseases. They yield 12 to 13% tannin (by dry weight).

The

leaves, stems, flowerbuds, opened blossoms, and bark have some

antibiotic activity. A decoction of the bark is taken internally for

dyspepsia, dysentery, and diarrhea and also serves as an enema. The

root bark is similarly employed. Bark decoctions are taken in cases of

asthma and bronchitis and are gargled or used as mouthwash for the

astringent effect on mouth ulcerations, spongy gums, and stomatitis.

Ashes of the bark, mixed with water, are spread over local

inflammations, or, blended with oil, applied to bums. In modern

therapy, tannin is no longer approved on burned tissue because it is

absorbed and can cause cancer. Excessive oral intake of tannin-rich

plant products can also be dangerous to health.

|

|