Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Ziziphus Mauritiana Lam.

Local Names: Amharic (kurkura);

Arabic (nabak (fruit), sidr); Bengali (ber boroi, kool, ber, boroi);

Burmese (zee-pen, zizidaw, eng-si); English (dunks, jujube, Indian

cherry, Indian jujube, Indian plum, geb, ber, common jujube, Chinese

date, Chinese apple, bear tree, desert apple); Filipino (manzanita);

French (jujube, jujubier, jujubier commun, le jujubier, le jujubier

sauvage, liane croc-chien); German (Indischer Jujubenstrauch); Gujarati

(bordi); Hindi (baer, badari, elladu, ber, khati, jelachi); Indonesian

(widara, dara, bidara); Khmer (putrea); Lao (Sino-Tibetan) (than); Malay

(bidara, jujub, epal siam); Mandinka (tomborongo, tomboron moussana,

toboro); Nepali (bayer); Sanskrit (kuvala, karkandhu, badara, ajapriya,

madhuraphala); Somali (geb, gub); Spanish (yuyuba, Ponseré,

perita haitiana); Swahili (mkunazi); Tamil (elandai, yellande); Thai

(ma thong, ma tan, phutsan); Tigrigna (geva); Trade name (jujube); Urdu

(ber); Vietnamese (tao nhuc, tao, c[aa]y t[as]o ta)

Family: Rhamnaceae

Botanic Description

Ziziphus mauritiana is

a spiny, evergreen shrub or small tree up to 15 m high, with trunk 40

cm or more in diameter; spreading crown; stipular spines and many

drooping branches. Bark dark grey or dull black, irregularly fissured.

Where climatic conditions are severe, it is commonly a compact shrub

only 3-4 m tall.

Leaves variable, alternate, in 2 rows,

oblong-elliptic, 2.5-6 x 1.5-5 cm, with tip rounded or slightly notched

base; finely wavy-toothed on edges, shiny green and hairless above;

dense, whitish, soft hairs underneath.

Inflorescence axillary

cymes, 1-2 cm long, with 7-20 flowers; peduncles 2- 3 mm long; flowers

2-3 mm across, greenish-yellow, faintly fragrant; pedicels 3-8 mm long;

calyx with 5 deltoid lobes, hairy outside, glabrous within; petals 5,

subspathulate, concave, reflexed.

Fruit a drupe, globose to

ovoid, up to 6 x 4 cm in cultivation, usually much smaller when wild;

skin smooth or rough, glossy, thin but tough, yellowish to reddish or

blackish; flesh white, crisp, juicy, subacid to sweet, becoming mealy

in fully ripe fruits. Seed a tuberculate and irregularly furrowed

stone, containing 1-2 elliptic brown kernels each 6 mm long.

The

name ‘Ziziphus’ is often erroneously written as Zizyphus.

The generic name is derived from the latinized version of the Arabic

vernacular name ‘zizouf’ for Z. jujuba.

Biology

Some

cultivars attain anthesis early in the morning, others do so later in

the day. The flowers are protandrous. Hence, fruit set depends on

crosspollination by insects attracted by the fragrance and nectar. The

pollen of the flower is described as ‘heavy and thick’. In

India, different species of honeybees (Apis spp.) and house flies (Musca domestica) are reported to be important pollinators; the wasps Polistes hebraceus and Physiphora

spp. have also been observed on flowers. Cross-incompatibility occurs,

and cultivars have to be matched for good fruit set; some cultivars

produce good crops parthenocarpically. Fruit development takes 4 months

in early cultivars to 6 months in late ones. In Southeast Asia, Z. mauritiana flowers concurrently with shoot growth in the wet season. Mammals and birds disperse the fruits.

Ecology

Z. mauritiana

is a hardy tree that copes with extreme temperatures and thrives under

rather dry conditions. Fruit quality is best under hot, sunny and dry

conditions, but there should be a rainy season to support extension

growth and flowering, ideally leaving enough residual soil moisture to

carry the fruit to maturity. Commercial cultivation usually extends up

to 1000 m. Beyond this elevation trees do not perform well, and

cultivation becomes less economical. Native to the tropical and

subtropical regions, Z. mauritiana

is more widespread in areas with an annual rainfall of 300-500 mm. It

is known for its ability to withstand adverse conditions, such as

salinity, drought and waterlogging.

Biophysical Limits

Altitude: 0-1 500 m, Mean annual temperature: 7-13 to 37-48 deg. C, Mean annual rainfall: 120-2 200 mm

Soil

type: Best soils are sandy loam which may be neutral or even slightly

alkaline. Can grow on a variety of soils including laterite, black

cotton and oolitic limestone.

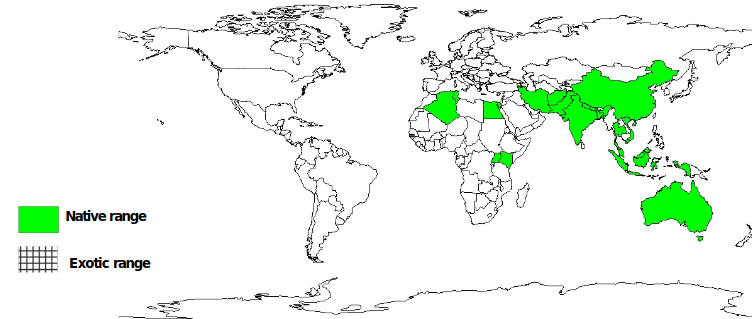

Documented Species Distribution

Native:

Afghanistan, Algeria, Australia, Bangladesh, China, Egypt, India,

Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Malaysia, Nepal,

Pakistan, Thailand, Tunisia, Uganda, Vietnam

Exotic: Angola, Barbados, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Cambodia, Cameroon, Chad,

Congo, Cote d'Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Grenada, Guinea,

Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mozambique, Namibia,

Niger, Nigeria, Philippines, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South

Africa, Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia, Zimbabwe

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food:

Fruit is eaten fresh or dried and can be made into a floury meal,

butter, or a cheeselike paste, used as a condiment. Also used for candy

making and pickling. The fruit is a good source of carotene, vitamins A

and C, and fatty oils. A refreshing drink is prepared by macerating

fruits in water. In Indonesia, young leaves are cooked as a vegetable.

Fodder: In parts of India and North Africa, the leaves of Z. mauritiana

are used as nutritious fodder for sheep and goats. Analysis of the

chemicals constituents on a dry weight basis indicates the leaves

contain 15.4% crude protein, 15.8% crude fibre, 6.7% total minerals,

and 16.8% starch. In India, the leaves are also gathered to feed tasar

silkworms; tasar silk, highly prized, is the only silk commercially

exploited in the tropics.

Fuel: Z. mauritiana

produces excellent firewood (sapwood has 4900 kcals/kg) and good

charcoal. Its drooping branches are easily accessible for harvesting.

Apiculture: When in bloom it is ocassionally a source of pollen, at best a minor one.

Timber: Z. mauritiana

yields a medium-weight to heavy hardwood with a density of 535-1080

kg/m³. Heartwood is buffcoloured, pale red or brown to dark brown,

sometimes banded or with dark streaks, not sharply demarcated from pale

brown sapwood; grain straight, occasionally wavy; texture fine to

coarse; wood fairly lustrous. It seasons well but may split slightly

during seasoning; easy to work and takes a high finish. It is hard and

strong. The wood is used for general construction, furniture and

cabinet work, tool handles, agricultural implements, tent pegs, golf

clubs, gun stocks, sandals, yokes, harrows, toys, turnery, household

utensils, bowling pins, baseball bats, chisels and packaging. It is

also suitable for the production of veneer and plywood. Basically, any

product that needs a durable, close-grained wood can be made from it.

Tannin or dyestuff:

The bark, including the root bark, has served in tanning; when pounded

and mashed in water, it yields brown and grey or reddish dyes.

Poison: Z. mauritiana is used to stupefy fish in Ethiopia.

Medicine:

Leaves, fruits and bark are used medicinally. Pounded roots are added

to drinking water and given to poultry suffering from diarrhoea and to

humans for indigestion.

Alcohol: A raw, intoxicating spirit is occasionally distilled from the fermented fruit pulp.

Other products: In India, Z. mauritiana trees are a host for the lac insects, Kerria lacca,

which are found on the leaves and make an orange-red resinous

substance. The purified resin makes the high-quality ber shellac that

is used in fine lacquer work and to produce sealing wax and varnish.

Services

Erosion control: A suitable species to aid in fixation of coastal dune sand.

Shade or shelter: The tree has been planted for shade and windbreaks.

Reclamation: Can withstand severe heat, frost and drought; hence it is planted in dry areas and on sites unfit for other crops.

Ornamental: Z. mauritiana is well suited for homegardens.

Boundary or barrier or support: Tree useful as a living fence; its spiny stems and branches deter livestock.

Tree Management

Z. mauritiana

is a fast-growing species. Under favourable conditions, height

increment on loose soil is 75 cm in 1 year and 1.2 m in 2 years; growth

is stragglier by the 3rd season, when under similar growth conditions

plants are thick and bushy, up to 1.5 m high. Growth is poor under

natural conditions, 5-8 cm high after 1st season and 17-35 cm after 2nd

season; Z. mauritiana coppices well and grows vigorously from stumps and root suckers. Fruiting starts after 3-5 years and is usually very abundant.

Germplasm Management

Orthodox

storage behaviour, viability maintained for 2 years in hermetic air-dry

storage at 5 deg. C. The germination rate increases during the 1st year

of storage. The cleaned stones can be kept for 5 years in sealed

containers, although during this period the viability drops from 95% to

30%. Z. mauritiana has 3300 pyrenes/kg.

Pests and Diseases

Fruit

flies are a major cause of crop losses, the insects unfortunately

having a preference for the same cultivars as humans. Damage by

fruit-borers, leaf-eating caterpillars, weevils, leafhoppers and mealy

bugs has also been reported. Insect pests include Meridarchis scyrodes, Oocussida cruenta, Myllocerus spp., Thiacidas postica, Drepanococcus chiton, Florithirps tregardhi and Systasis

spp. Powdery mildew can be so serious that leaves and fruitlets drop,

but it can be adequately controlled. Lesser diseases are sooty mould,

brown rot and leaf-spot.

Further Reading

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Beentje HJ. 1994. Kenya trees, shrubs and lianas. National Museums of Kenya.

Bekele-Tesemma

A, Birnie A, Tengnas B. 1993. Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia.

Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International

Development Authority (SIDA).

Birnie A. 1997. What tree is that? A beginner's guide to 40 trees in Kenya. Jacaranda designs Ltd.

Booth

FEM, Wickens GE. 1988. Non-timber uses of selected arid zone trees and

shrubs in Africa. FAO Conservation Guide. No. 19. Rome.

Coates-Palgrave K. 1988. Trees of southern Africa. C.S. Struik Publishers Cape Town.

Dale IR, Greenway PJ. 1961. Kenya trees and shrubs. Buchanan’s Kenya Estates Ltd.

Eggeling. 1940. Indigenous trees of Uganda. Govt. of Uganda.

Hocking D. 1993. Trees for Drylands. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. New Delhi.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

ICRAF.

1992. A selection of useful trees and shrubs for Kenya: Notes on their

identification, propagation and management for use by farming and

pastoral communities. ICRAF.

Jackson JK. 1987. Manual of afforestation in Nepal. Department of Forestry, Kathmandu.

Jothi

BD, Tandon PL. 1995. Present status of insect pests of ber in Karnataka

current research. University of Agricultural Sciences, (Banglore).

24:153-155.

Kokwaro JO. 1976. Medicinal plants of East Africa. East African Literature Bureau.

Little

EL, Wadsworth FH. 1964. Common trees of Puerto Rico and the Virgin

Islands. Agricultural Handbook. No. 249. US Department of Agriculture.

Washington DC.

Mbuya LP et al. 1994. Useful trees and shrubs for

Tanzania: Identification, Propagation and Management for Agricultural

and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU),

Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Noad T, Birnie A. 1989. Trees of Kenya. General Printers, Nairobi.

Parkash

R, Hocking D. 1986. Some favourite trees for fuel and fodder. Society

for promotion of wastelands development, New Delhi, India.

Perry LM. 1980. Medicinal plants of East and South East Asia : attributed properties and uses. MIT Press. South East Asia.

Peter G von Carlowitz.1991. Multipurpose Trees and Shrubs-Sources of Seeds and Innoculants. ICRAF. Nairobi, Kenya.

Schomburg

A, Mhango J, Akinnifesi FK. 2001. Marketing of masuku uapaca kirkiana

and masawo Ziziphus mauritiana fruits and their potential for

processing by rural communities in southern Malawi: Proceeding of the

14th southern Africa regional review and planning workshop, 3-7th

September 2001, Harare, Zimbabwe. p.169-176.

Singh RV. 1982. Fodder trees of India. Oxford & IBH Co. New Delhi, India.

Sosef

MSM, Hong LT, Prawirohatmodjo S. (eds.). 1998. PROSEA 5(3) Timber

trees: lesser known species. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Tembo L,

Chiteka ZA, Kadzere I, Akinnifesi FK, Tagwira F. 2008. Blanching and

drying period affect moisture loss and vitamin C content in Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk.: African Journal of Biotechnology. 7(8):3100-3106.

Tembo L, Chiteka ZA, Kadzere I, Akinnifesi FK, Tagwira F. 2008. Storage temperature affects fruit quality attributes of Ber Ziziphus mauritiana Lamk. in Zimbabwe: African Journal of Biotechnology. 7(8):3092-3099.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Vimal OP, Tyagi PD. Fuelwood from wastelands. Yatan Publications, New Delhi, India.

Vogt

K. 1995. A field guide to the identification, propagation and uses of

common trees and shrubs of dryland Sudan. SOS Sahel International (UK).

|

|