Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide

version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Macadamia

integrifolia Maiden

et Betche

Local Names:

English (smooth macadamia nut, Queensland nut, macadamia nut,

Australian bush nut)

Family:

Proteaceae

Botanic

Description

Macadamia

integrifolia is a large, spreading, evergreen tree

attaining a height of 18 m and a crown of 15 m.

Leaves

in whorls of 3, oblong to oblanceolate, 10-30 x 2-4 cm, glabrous,

coriaceous, irregularly spiny-dentate when young, entire in later

stages; petiole 5-15 mm long; 3 buds arranged longitudinally in the

axil of each leaf usually only the top bud shoots out, making a sharply

acute angle with the trunk.

Racemes axillary on mature new

growth or on leafless older shoot, pendulous, 10-30 cm long, with

100-500 flowers; flowers in groups of 2-4, about 12 mm long,

creamy-white; pedicles 3-4 mm long; perianth tubular with 4 petaloid

sepals.

Fruit a globose follicle, 2.5-4 cm in diameter; pericarp

fibrous, about 3 mm thick. Seed (nut) usually 1, globular, with a

smooth, hard, thick (2-5 mm) testa enclosing the edible kernel.

The genus is named after J. Macadam (1827-1865), secretary of the

philosophical Institute of Victoria. The specific name integrifolia is

from the Latin integri-‘entire’ and folium-‘a leaf’ in allusion to the

grouping of leaves in whorls of four.

Biology

Floral initiation

takes place when temperatures drop and trees become quiescent in

autumn, the optimum temperature being 18 deg. C. The initials remain

dormant for 50-96 days; the racemes extend after a rise in temperature

and some rain. In Australia high yields are associated with a strong

and early spring flush before anthesis, followed by minimal shoot

growth throughout the 6-month nut development period. At the end of nut

development, there is a late summer flush; meanwhile nuts may be

retained on the tree for a further 3 months, but gradually they fall.

The

flowers are protandrous, the anthers dehiscing 1-2 days before

anthesis, whereas the stigma does not support pollen tube growth until

1-2 days after anthesis.

Pollination is by insects; most

cultivars are at least partly self-incompatible. Planting pollinator

trees and introducing bees are important for good fruit set. Fruitlets

continue to be shed up to 2 months after bloom.

Ecology

M.

integrifolia

prefers well-drained soils, shelter from winds and a mild, frost-free,

subtropical climate with well-distributed annual rainfall of at least 1

200 mm. It occurs naturally in the fringes of subtropical rainforests.

It appears to tolerate only a narrow range of temperatures (optimum

during the growing season is 25 deg. C). Temperature is the major

climatic variable determining growth and productivity. Trees in

Southeast Asia grow fairly well but flower and fruit sporadically

throughout the year. In eastern Africa, orchards are planted at

elevations of 1 000-1 600 m in areas with a prominently seasonal

climate, leading to a synchronous resumption of growth and flowering

over a cool, overcast season. Abnormal tree growth, low yield and poor

nut quality have been noted in Africa at higher altitudes with little

sunshine during the flowering and fruiting season.

The

xerophytic characteristics of the tree, including the sclerophyllous

leaves and proteoid roots (dense clusters of rootlets formed to explore

poor soils low in phosphorus) suggest adaptation to relatively harsh

environments. However, the conditions required for optimum production

may be quite different from those for survival. Mature M. integrifolia is

capable of withstanding mild frosts, but only for short periods. The

brittle wood makes trees susceptible to wind damage.

Biophysical

Limits

Altitude: 0-1 600 m, Mean annual temperature: 15- 25 deg. C, Mean

annual rainfall: 700-3 000 mm

Soil type: M.

integrifolia

can be grown in a wide range of soils including poor soils, but not on

heavy, impermeable clays and saline or calcareous soils. It is most

suited to deep, well-drained loams and sandy loams with good organic

matter content, medium cation exchange capacity and pH of 5-6.

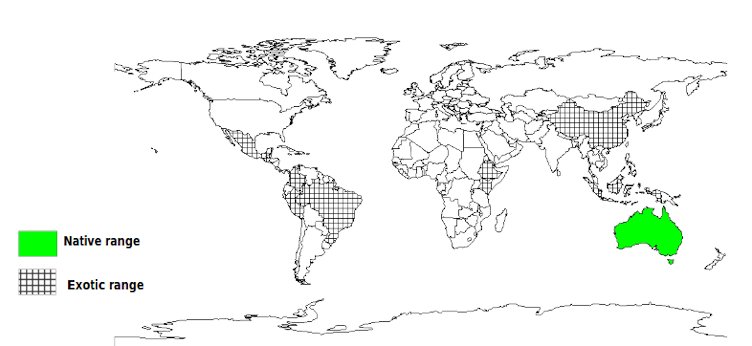

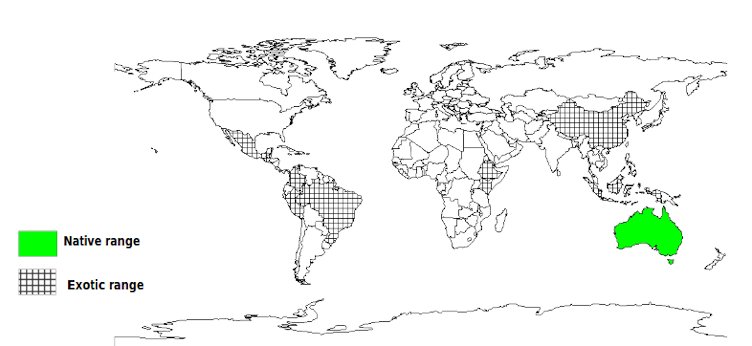

Documented

Species Distribution

Native:

Australia

Exotic:

Brazil, China,

Colombia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Guatemala, Indonesia, Kenya, Malawi, Mexico,

Peru, Samoa, South Africa, Tanzania, Thailand, US, Venezuela, Zimbabwe

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food:

The fine, crunchy

texture, rich cream colour and delicate flavour make the macadamia nut

one of the finest dessert nuts. The eating quality of the nut is

enhanced by lightly roasting it in coconut oil and salting. Raw kernels

are also popular alone or in a wide range of confectionery and

processed foods. The quality of the kernel is related to its oil

content and composition. Nuts are mature when the kernels accumulate

72% or more oil, as determined by specific gravity. Kernels also

contain 10% carbohydrates; 9.2% protein, which is low in methionine;

0.7% minerals, particularly potassium;, and niacin, thiamine and

riboflavin.

Apiculture: Macadamia

pollen is very attractive to bees, providing necessary forage for honey

production.

Macadamia shells may be used as fuel, generating sufficient energy to

dry wet, in-shell nuts.

Shade or

shelter: M.

integrifolia makes an excellent evergreen shade and

shelter due to its thick crown of leaves.

Tannin or

dyestuff: The hulls, the green covering of the

nuts, contain approximately 14% of substances suitable for tanning

leather.

Lipids: Macadamia

is the richest oil-yielding nut known. The kernel contains more than

75% oil, suitable for human consumption.

Essential oil: The

characteristic, subtle macadamia flavour is probably due to volatile

compounds, the major ones being similar to those in other roasted nuts.

Services

Ornamental: As

well as being an evergreen nut-bearing tree, M. integrifolia

has good symmetrical shape and when in full bloom is covered with

creamy-white and pinkish flowers in long, narrow, drooping racemes.

These make it a popular ornamental tree.

Soil improver: The

decomposed husk is commonly used in potting soil.

Intercropping: Inter-row

cropping can be practised with trees such as citrus, if they are

removed at 12 years. Macadamia will retard the growth of papaya planted

near it.

Tree

Management

M.

integrifolia

comes reasonably true to type when raised from seed. Seeds for

propagation are selected from vigorous, heavy-bearing trees. The fresh

nuts are planted with no pretreatment.

Grafting may develop

desirable clones; side wedge grafting has been used exclusively in

Hawaii. Other vegetative propagation methods include splice grafting

and cuttings.

Seedling growth, initially slow, gathers momentum

as saplings produce a series of extension growth flushes in a year. The

juvenile phase lasts for 7 years or more, but grafted trees come into

bearing after 3 years. The current trend is for high-density hedgerow

plantings, which maximize early yields. Inter-row spacing of 10 m is

most common (7 m if mechanical pruning is carried out). The distance

between rows should be 4-6 m, depending on cultivar and growing

conditions.

Correct branching should be induced at an early

age after which there should be no further pruning. During the first 2

years, training (a form of corrective pruning) is done to develop a

strong, well-balanced framework for future growth. The young trees

should receive careful attention with respect to irrigation, weed

control and frost and wind protection. They should also be fertilized

to make them grow well and induce early flowering.

Mulching is

recommended for young trees (when the trees come into bearing, it

interferes with nut collection). Fertilizer management should be guided

by leaf and soil analysis, the phenological cycle and yield. Macadamia

trees appear to be sensitive to nutrient deficiencies and imbalances,

and positive responses to N, P, K, Zn, B, S, Mg, Fe and Cu have been

observed.

Yields of 45 kg nuts-in-shell from better trees or an average of

3.2-3.5 t/ha per year are obtained in Hawaii.

Germplasm

Management

Seed storage behaviour is uncertain. Drying until the kernel rattles in

the shell does not harm viability; no loss of viability during 4 months

of storage in paper bags at room temperature, after which time

viability is reduced, and none survives after 12 months. No loss in

viability after 12 months of storage in polythene bags at 12 deg. C;

viability maintained for 24 months with partially dried seeds at 15

deg. C.

Pests and

Diseases

In their

place of origin macadamias are attacked by more than 150 pest species,

although parasites and predators usually provide considerable control.

Insects that commonly reduce yields include macadamia flower

caterpillar (Homoeosoma

vagella), fruit spotting bug (Amblypelta nitida),

banana spotting bug (A.

lutescens), macadmia nutborer (Cryptophlebia ombrodelta),

and macadamia felted coccid (Eriococcus

ironsidei). Any of these have the capacity to destroy much

of the crop during severe infestations. The macadamia twig-girdler (Neodrepta luteotacetella)

and macadamia leafminer (Acrocercops

chionosema)

destroy foliage and may therefore reduce yield indirectly. Many of the

minor macadamia insect pests cause damage sporadically. Rats are

particularly fond of macadamia nuts and can be a problem in some areas.

In comparison with other fruit trees, relatively few diseases are

serious in macadamia.

Further

Reading

Allan P. 1969. Macadamia production overseas. Farming South Africa.

45(2):29-32.

Cann HJ. 1965. The macadamia: Australia’s own nut. The Agricultural

Gazette. 76(2):78-84.

Doran

CJ, Turnbull JW (eds.). 1997. Australian trees and shrubs: species for

land rehabilitation and farm planting in the tropics. ACIAR monograph

No. 24, 384 p.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a

compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

Lemmens

RHMJ, Soerianegara I, Wong WC (eds.). 1995. Plant Resources of

South-east Asia. No 5(2). Timber trees: minor commercial timbers.

Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Robinson JC. 1966. The macadamia nut tree. Hortus. 6:4-6.

Tonks EP. 1968. The macadamia. Shell Farmer. 11(3):1-8.

Verheij

EWM, Coronel RE (eds.). 1991. Plant Resources of South East Asia No 2.

Edible fruits and nuts. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

Wickens GE (ed.). 1995. Non-wood forest products 5; Edible nuts. FAO,

Rome.

|

|