From the Manual Of Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Mango

Propagation

Like many other fruit-trees, the mango has been propagated in the

tropics principally by seed. In some instances seedling trees produce

good fruits; this is particularly true of certain races, such as the

Manila or Philippine. But in order to insure early bearing,

productiveness, and uniformity of fruit, it is necessary to use

vegetative means of propagation. Inarching, budding, and grafting are

the methods most successfully employed.

The seedling races of

the tropics are, so far as has been observed, polyembryonic in

character. Three to ten plants commonly grow from a single seed. Since

these develop vegetatively from the seed tissues, they are not the

product of sexual reproduction, but may be compared to buds or cions

from the parent tree. Most of the grafted Indian varieties, on the

other hand, have lost this characteristic. When their seeds are planted

a single young tree develops, and this is found to differ from its

parent much as does a seedling avocado or a seedling peach. Usually the

fruit is inferior, and the tree may be quite different in its bearing

habits.

Dr. Bonavia, a medical officer in British India who did

much to stimulate interest in mango culture, at one time took up the

question of seedling mangos and wrote several articles advocating their

wholesale planting. He argued that not only would many new varieties,

some of them superior in quality, be obtained in this way, but also

earlier and later fruiting kinds, and perhaps some suited to colder

climates.

Just what percentage of seedling mangos will produce

good fruit depends largely on their parentage. Seedlings of the fibrous

mangos of the West Indies are invariably poor, while those from budded

trees of such varieties as Alphonse and Pairi, although in most

instances inferior or rarely equal or superior to the parent, are

practically never so poor as the West Indian seedlings. At the

Saharanpur Botanic Gardens, in northern India, some experiments were

conducted between 1881 and 1893 to determine the average character of

seedlings from standard grafted varieties. The results led to the

conclusion that seedlings of the Bombay mango were fairly certain to

produce fruit of good quality. An experimenter in Queensland, at about

the same time, reported having grown seedlings of Alphonse to the

fourth generation, all of which came true to the parent type.

Experience

in the United States has shown, however, that degeneration is common. A

number of seedlings of Mulgoba have been grown in Florida, but very few

have proved of good quality. There is a tendency for the fruits to be

more fibrous than those of the parent. The whole question is probably

one of embryogeny. When monoembryonic seeds are planted, the fruit is

likely to be inferior to that of the parent, if the latter was a choice

variety; with polyembryonic seeds, even though of fine sorts like the

Manila, the trees produce fruit closely resembling that of the parent.

The

embryogeny of the mango cannot be discussed at great length here. It is

not yet thoroughly understood, although it has been studied by several

investigators. The most recent account and the only one which has been

undertaken with the horticultural problems in mind, is that of John

Belling, published in the Report of the Florida Agricultural Experiment

Station for 1908. Belling says:

"In the immature seed of the

sweet orange E. Strasburger has shown by the microscope, and Webber and

Swingle have proved by their hybridizing experiments that besides the

ordinary embryo which is the product of fertilization, the other

embryos present in the young or mature seeds arise by the outgrowth of

nucellar cells into the apical part of the embryo-sac. The

first-mentioned embryo, when present, is liable to any variation which

is connected with sexual multiplication, - the vicinism of H. De Vries.

The remaining embryos, on the other hand, presumably resemble buds from

the tree which bears the orange in whose seed they grow, in that they

inherit its qualities with only a minor degree of variation."

The

behavior of the mango has suggested a similar state of affairs. Belling

goes on to quote Strasburger's account of the embryogeny of the mango,

and describes his own investigations:

"Even in the unopened

flower bud the nucellar cells at the apex of the embryo sac which are

separated from the sac only by a layer of flattened cells, are swollen

with protoplasm. In older fruits it may be noticed that the cells

around the apical region of the sac except on the side near the raphe

are also swollen. The adventitious embryos arise from these swollen

cells, which in fruits 7 mm. long with ovules 3 mm. long divide up,

sometimes forming the rudiments of a dozen or more embryos, but often

fewer. The nucleated protoplasm on the embryo-sac wall is undivided

into cells, and is thick opposite the places where embryo formation is

going on."

Belling worked with fruits of the No. 11 mango,

seedling race of Florida identical with the common mango of the West

Indies, Mexico, and Central America. He was not able to determine

whether the egg-cell develops into an embryo, or whether all of the

embryos are adventitious, - the egg-cell being crowded out or destroyed

in some other way. If the fertilized egg-cell develops and is

represented in the mature seed, the plant arising from it should

exhibit variation; but the seedling races are so constant that it seems

probable that the egg-cell is lost at some stage in the development of

the fruit, and that all of the embryos are normally adventitious. There

is as yet no proof, however, that fruits will develop on this or other

mangos unless the flowers are pollinated. The subject is an important

one and will repay further investigation.

It has been observed

in Florida that monoembryonic grafted varieties, such as Mulgoba, will,

when grown from seed, sometimes revert to polyembryony in the first

generation (Fig. 10).

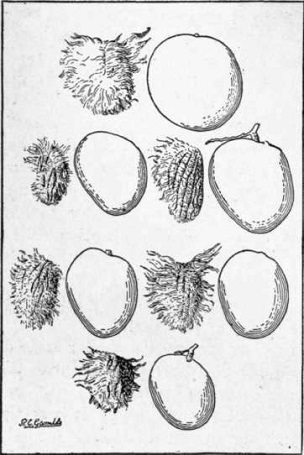

Fig. 10. Seedlings of grafted Indian mangos usually do not produce

fruit exactly like the parent. Each of the fruits here shown represents

a tree grown from a seed of the Mulgoba mango. The variations in size

and shape of fruit, and in the amount of fiber around the seed, are

noteworthy. (X 1/6)

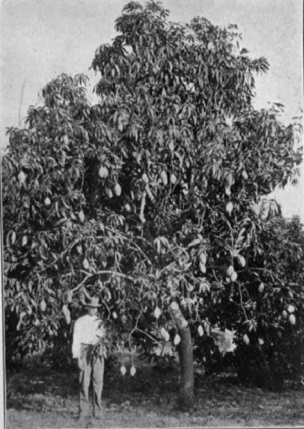

|  | | Plate VI. Left, the Sandersha mango; right, the ambarella. |

G. L. Chauveaud1

has advanced the theory that polyembryony is a more primitive state

than monoembryony, which would seem to be borne out by this

observation; for it must be true that the choice mangos of India which

have been propagated by grafting for centuries are less primitive in

character than the semi-wild seedling races.

Inarching is an

ancient method of vegetative propagation. While several writers have

attempted to show that it was not known in India previous to the

arrival of Europeans, and that the Jesuits at Goa were the first to

apply it to the mango, others have held the belief, based on researches

in the literature of ancient India, that the Hindus propagated their

choice mangos by inarching for centuries before any Europeans visited

the country.

This method of propagation is still preferred to

all others in India and a few other countries. In the United States it

has been superseded by budding.

For the production of stock

plants on which to bud or graft choice varieties, seeds of any of the

common mangos are used. No preference for any particular race has yet

been established. It is reasonable to believe, however, that there may

be important differences among seedling races in vigor of growth and

perhaps in their effect on the productiveness and other characteristics

of the cion. The subject has never been investigated and deserves

attention.

Seeds are planted, after having the husk removed, in

five- or six-inch pots of light soil or in nursery rows in the open

ground. They are covered with 1 inch or 1 1/2 inches of soil. In warm

weather they will germinate within two weeks, and must be watched to

prevent the development of more than one shoot. Polyembryonic mangos

will send up several; all but the strongest one should be destroyed. If

grown in pots and intended for budding, the young plants may be set out

in the field in nursery rows when they are a foot high. If destined for

inarching they must be kept in pots.

1 Compt. Rend. 114, 1892.

Inarching

is more successful in the hands of the tyro than budding or

crown-grafting. It can be recommended when only a few plants are

desired, and when the tree to be propagated is in a convenient

situation. G. Marshall Woodrow thus describes inarching as it is done

in India. A slice is cut from the side of a small branch on the tree it

is desired to propagate, and a slice of similar size - 2 to 4 inches

long and deep enough to expose the cambium - is cut from the stem of a

young seedling supported at a convenient height upon a light framework

of poles. The two cut surfaces are bound together with a strip of fiber

from the stem of the banana, or with some other soft bandage.

Well-kneaded clay is then plastered over the graft to keep out air and

water. The soil in the pot must be kept moist. After six to eight weeks

the cut surfaces will have united.

Inarching may be done at any

time in strictly tropical climates, but the best time in the hot parts

of India is the cool season. Toward the northern limits of mango

cultivation the middle of the rainy season is better.

The graft

is sometimes allowed to remain attached to the parent tree for too long

a time, with the result that swellings, due to the constriction of the

bandages, occur at the point of union. It is better to remove the

grafted plant fairly early and place it in the shade for a few weeks.

It is detached from the parent tree by severing the branch which has

been inarched to the seedling at a point just below the point of union

with the latter. This leaves the young branch from the tree it was

desired to propagate growing upon a seedling; the top of the latter is

cut out, and the branch from the old tree takes its place, ultimately

forming the crown of the mature tree.

The age of the stock is

not important. Plants three weeks to three years old have been used

with success. If kept in pots too long, however, the plants become

pot-bound and lose their vigor; hence it is desirable to graft them

when young and get them into the open ground as soon as possible. Seeds

planted in June and July make strong plants ready for inarching by

November. December and January are good months in which to inarch, and

such plants should be ready to set out in the field by the following

July.

Inarching, as practiced in other countries, differs in no essentials from the Indian method above described.

Shield-budding

is the method employed by nurserymen in Florida. In the hands of a

skillful propagator who has made a careful study of this method, it

gives excellent results. In inexperienced hands it usually proves

altogether unsatisfactory. Particularly is experience required to

enable the propagator to recognize the proper type of bud wood, and to

know when the stock plants are in the proper state of vegetative

activity. By careful experimenting with stock plants and budwood of

different conditions of growth throughout a season or two, a good

propagator should be able to bud mangos successfully; but comparatively

few men have yet devoted the requisite time and study to the subject.

Thus there are at present only a few propagators in the United States

who can produce budded mango trees economically and in quantity.

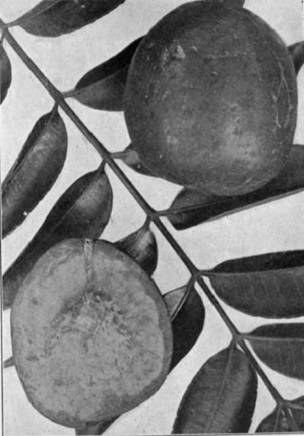

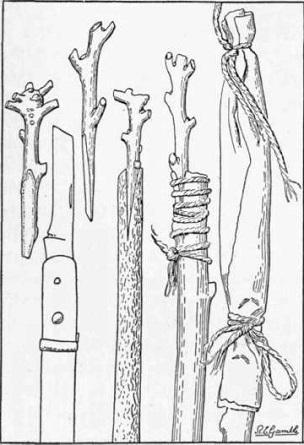

Fig.

11. Shield-budding the mango. On the left, a bud properly inserted;

next, an inserted bud wrapped with a strip of waxed cloth; above the

knife-point, a properly cut bud; and on the right, budwood of desirable

character.

Various

methods of budding, beginning with the patch-bud, have been tried at

different times, but shield-budding (Fig. 11) is the only one which has

proved altogether satisfactory for nursery purposes. The method is the

same as that used with citrus fruits and the avocado. Having been less

extensively practiced, however, mango budding is less thoroughly

understood, and it is not a simple matter to judge the condition of the

stock plants and the bud wood without experience.

The best

season for budding the mango in Florida is generally considered to be

May and June, but the work is done successfully all through the summer.

It is necessary to bud in warm weather, when the stock plants are in

active growth.

When seedlings have attained the diameter of a

lead-pencil they can be budded, although they are commonly allowed to

grow a little larger than this. The proper time for inserting the buds

is when the plants are coming into flush, i.e., commencing to push out

wine-colored new growth. When they are in this stage, the bark

separates readily from the wood; after the new growth has developed

further and is beginning to lose its reddish color, the bark does not

separate so easily and budding is less successful.

The budwood

should be taken from the ends of young branches, but usually not from

the ultimate or last growth; the two preceding growths are better. It

is considered important that budwood and stock plant be closely

similar, in so far as size and maturity of wood are concerned. If

possible, branchlets from which the leaves have fallen should be

chosen. In any event, the budwood should be fairly well ripened, and

the end of the branchlet from which it is taken should not be in active

growth.

The incision is made in the stock plant in the form of a

T or an inverted T, exactly as in budding avocados or citrus trees. The

bud should be rather large, preferably 1 1/2 inches in length. After it

is inserted it should be wrapped with waxed tape or other suitable

material.

After three to four weeks the bud

is examined, and if it is green and seems to have formed a union, the

top of the stock plant is cut back several inches to force the bud into

growth. A few weeks later the top can be cut back still farther, and

eventually it may be trimmed off close above the bud, - this after the

bud has made a growth of 8 or 10 inches.

J. E. Higgins1

describes a method of shield-budding which has been successful in the

Hawaiian Islands. So far as known, it has not been used on the mainland

of the United States. Higgins says, "Budding by this method has been

successfully performed on stocks from an inch to three inches in

diameter. . . . Wood of this size, in seedling trees, may be from two

to five years old. It is essential that the stocks be in thrifty

condition, and still more essential that they should be in ' flush.' If

not in this condition, the bark will not readily separate from the

stock. It has been found that the best time is when the terminal buds

are just opening. . The budwood which has been most successfully

used is that which has lost most of its leaves and is turning brown or

gray in color. Such wood is usually about an inch in diameter. It is

not necessary in this method of budding that the budwood shall be in a

flushing condition, although it may be of advantage to have it so. . .

The incision should be made in the stock about six inches in length.

. . . The bud shield should be three to three and a half inches long,

with the bud in the center." After-treatment of the buds is the same as

with the Florida method which has been described: in fact the Hawaiian

method seems distinct only in the size of stock plant and budwood, and

the consequent larger size of the bud.

1 Bull. 20, Hawaii Agr. Exp. Sta.

Crown-grafting

(Fig. 12) is not commonly practiced in Florida, but it has been

successful in Porto Rico. It has also been employed with good results

by H. A. Van Hermann of Santiago de las Vegas, Cuba, and it is said to

have proved satisfactory in Hawaii and in India. W. E. Hess, formerly

expert gardener of the Porto Rico Agricultural Experiment Station, who

has had much experience with the method, says that it has proved more

successful in Porto Rico than budding, and is at the same time superior

to inarching because of the greater rapidity with which trees can be

produced in large quantities. As in budding, success seems to depend

mainly on the condition of stock and cion at the time the graft is

made. Provided the stock is in flush, the work can be done at any

season of the year. For cions, tip ends of branchlets are used. They

should be of about the diameter of a lead-pencil; of grayish, fully

matured, dormant wood; and from 3 to 5 inches in length. A slanting cut

1 to 2 inches long is made on one side, tapering to a point at the

lower end of the cion. The stock may be of almost any size. When young

plants are used they are cut back to 1 foot above the ground, and a

slit about 1 inch long is made through the bark, extending downward

from the top of the stump. The cion is then forced in, with its cut

surface next to the wood, and is tied in place with soft cotton string.

No wax is used. The graft is inclosed in three or four thicknesses of

oiled paper which is wound around the stock and tied firmly above and

below. This is left on for twelve to twenty days, when it is untied at

the lower end to admit air. Fifteen or twenty days later the cions will

have begun to grow and the paper can be removed entirely.

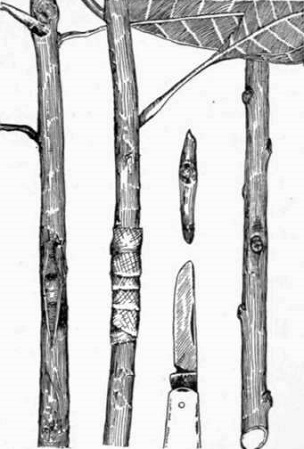

Fig.

12. Crown-grafting the mango. On the left, two cions of proper size and

character; in the center, a cion inserted and another tied in place;

and on the right, the covering of waxed paper which protects the cion

while it is forming a union with the stock.

This method is

applicable not only to nursery stock but also to old trees which it is

desired to topwork. In this case about half of the main branches of the

tree should be cut off at three or four feet from their union with the

trunk. It is necessary to leave several branches to keep the tree in

active growth; this also has a beneficial effect on the grafts by

protecting them from the sun. When the cions are well established,

these branches may be removed or they also may be grafted if more limbs

are necessary to give the tree a good crown. The cions are inserted

under the bark at the cut ends of the limbs, exactly as described for

young stocks, but larger cions may be used.

In Florida many

large trees have been top-worked by cutting off several of the main

branches, close to their union with the trunk, and allowing a number of

sprouts to come out. When these have reached the proper size, they are

budded in the same manner as seedlings.

Throughout the tropics

there are many thousands of seedling mango trees which are producing

fruit of inferior quality. By top-working, these trees could be made to

yield mangos of the choicest Indian varieties. The work is not

difficult and the value of the tree is increased enormously. Perhaps no

other field in tropical horticulture offers such opportunities for

immediate results as this.

The Mango

Botanical

Description

History and

Distribution

Composition

And Uses Of The Fruit

Climate And Soil

Cultivation

Propagation

The Mango Flower

And Its Pollination

The

Crop

Pests And

Diseases

Races and

Varieties

Back to

The Mango Page

|

|