Cultivars

With

over 800 named olive cultivars available world-wide, specific cultivars

are selected on the basis of their usefulness for preserving as table

olives or for making olive oil. Although all olive cultivars can be

eaten or crushed for oil, those preferred as table olives generally

have a greater water content and lesser oil content than those used to

make oil. Table olives are usually larger than those for oil which

makes the latter more difficult to pick by shaking. Future picking

methods may follow technologies being developed for the grape industry.

Furthermore each country has its own traditional cultivars such as

Picual in Spain, Leccino in Italy and Kalamata in Greece. Some country

specific cultivars are listed below.

Algeria - Sigoise

Australia - Swan Hill (non-fruiting)

Chile - Azapa

Cyprus - Adrouppa

Egypt - Aghizi Shami

France - Picholine

Greece - Kalamata, Koroneiki, Mastoides

Israel - Barnea, Nabali, Souri

Italy - Ascolana, Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolina, Carolea

Morocco - Picoline Marocaine

Portugal - Blanquita de Elvas, Cobranosa

Spain - Arbequina, Picual, Sevillano, Manzanillo

Tunisia - Chemlali

Turkey - Memeli, Ayvalik, Domat

USA - - Californian Mission, UC13A6

Cultivar

selection for a grove can also be made on the basis of fruiting period,

resistance to frost or disease and usefulness as root stock. In

Australia for olive oil production there is interest in planting the

cultivars Frantoio, Leccino, Pendolina, Picual and Paragon for oil

production.

Newer cultivars for Australia, some of which are

still in Australian quarantine, include Barnea (Israel), Koroneiki

(Greece) and Minerva (Italy). These cultivars can be trained into

medium sized trees, which are less labour intensive to manage. Fruit

from these cultivars yield about 20-25% oil. There is also interest in

developing DNA identified cultivars from wild olives growing in

Australia as Australian cultivars.

It has been estimated that in

olive oil production, cultivars contribute about 20% to the quality of

the oil with most of the quality being attributed to regional effects,

harvesting and the oil production process. The axiom is that you need

high quality olives to produce high quality oil. If it is any

consolation, less than one third of the olive oil produced world-wide

meets the extra virgin standards. So world consumers are using lesser

quality olive oils often labelled as olive oil or pure olive oil. The

latter olive oils make up the bulk of olive oils marketed in Australia

for table use and in the manufacture of olive oil margarines and

blended oils. When Australia becomes a major olive oil producer, even

though the industry will be aiming for the quality end of the market,

facilities will need to be developed to process lesser quality olive

oils to international standards.

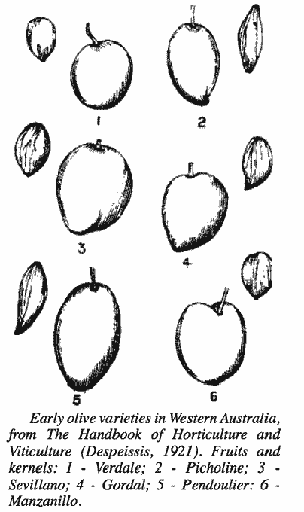

In the case of table olives,

consumers prefer a fleshy fruit with a high flesh to pit ratio. Olives

that are recognised as excellent table olives include Kalamata, Volos,

Sevillano and Manzanillo. All grow well in most parts of Australia

although Manzanillo does better in warmer climates. There is no doubt

that those wanting to grow table olives should consider the Kalamata

variety. Verdale has also been a popular table olive in Australia in

the past, however it will become less important as more new cultivars

become available.

Olive Tree Propagation

Traditionally

olive trees have been propagated by grafting onto seedlings. Grafting

is still the preferred method for difficult to strike cultivars such as

the Kalamata variety. For most cultivars, current practice is to strike

pencil length vigorous shoots using indolebutyric acid. Several regimes

are available. Commonly cuttings taken in autumn are dipped for a few

seconds in IBA (3-4000 ppm), placed in a synthetic medium such as

perlite or peat moss and then kept moist in a propagating house with

intermittent fog and spray and bottom heat. Rooting takes 2-3 months,

after which the rooted cuttings are planted out into plastic bags. For

serious growers tree propagation should be left to the experts.

Olive Grove Design

There

is much discussion regarding the spacings, planting protocols and form

for olive trees. Several questions need to be asked.

• what will be the size of the grove?

• which cultivars will be planted?

• will the trees be grown under rainfed conditions or will the grove be irrigated?

• what is the quality of the water?

• what is the quality of the soil?

• what level of mechanisation will be used?

Olive

trees need maximum sunlight and training by selective pruning will

ensure that the outer growing area of the crown where the olive fruit

develops is maximised. Olives develop on one year old wood. Under

rainfed conditions tree spacing needs to be greater than if irrigated

to allow for effective root development. For example in countries with

very low rainfall such as Tunisia, olive trees are spaced 20 m apart. A

9 m by 9 m spacing will allow a tree density of 120 trees/Ha whereas 6

m by 6 m planting will give 250 trees/Ha. For the UWA research trials

we will be using a 5 m by 7 m planting design. Trees will be planted 5

m apart and the inter-row spacing will be 7 m. The reason for the

latter is to allow for machinery to pass between the rows. For

irrigated groves the inter-tree spacing can be reduced with increased

risk of shading. Shading reduces budding and fruiting and orchard

production.

Early in the development of an olive grove, the

inclusion of filler trees has been suggested so that commercial yields

will be obtained earlier. The idea is that these filler trees are re-

moved as the main trees grow. The economics for such an exercise have

not yet been proven, and unless there is a shortage of land, should not

be considered. It is far better to plant the trees in their permanent

position.

Planting Olive Trees

Olives

grow on a variety of soils good and poor. Some planting regimes suggest

deep ripping. This is more important where old root systems are present

and for heavy and loamy soils likely to compact. Deep ripping is less

important for sandy soils. Rotted organic material such as straw,

animal manures, blood and bone worked in to the soil prior to planting

has been shown to be advantageous. Some commercial growers also

recommend the application of commercial formulations of slow release

fertilisers. Where soils are phosphate deficient or acidic,

superphosphate or dolomite can be worked into the soil. Although

herbicides are suggested to keep down weeds, mulching is a more

environmentally friendly process. Growing a winter legume for green

mulch is another strategy that should be considered. More research is

required to determine nitrogen production from biological sources to

reduce the need to add chemical fertilisers and so reduce the risks of

pollution. Mechanical tilling particularly after harvest assists in

improving water absorption, however promotes erosion and loss of top

soil and should not be the preferred method for weed control.

Least

problems will occur if olive trees are planted in autumn or spring.

When planting olives, a hole big enough to take the roots should be

dug, avoiding any glazing of the sides. Trees should be planted at a

level lower than the top of the soil in the pot or bag. Grafted olives,

such as Kalamata variety, should have the graft planted well below the

ground. This will reduce the risk of losing grafted stems as well as

promote root formation from the grafted variety. Trees should be

watered immediately after planting and every couple of weeks especially

during prolonged hot dry periods. Apart from water some protection from

sun and small animals may also be necessary. This can be achieved by

painting the trunks with white house type plastic paint or by using

milk canons. A stout 2 m wooden or metal stake can also be of some use

in windy conditions and for training the olive trees.

Irrigation

Irrigation

is essential for large commercial orchards. A planned irrigation regime

will allow the orchard to develop faster, yield earlier than under

rainfed conditions, increase the yield and reduce the biennial bearing

effects. characteristic of the olive tree. The type of system used will

depend on the availability of water, the soil type and the tree

spacing. Water is required over the hot summer period particularly when

the fruit is developing. One thing for sure, in hot dry areas it is

better to give the olive trees the water than to waste it to

evaporation. The irrigation period is generally between November and

April. This will depend on whether the site receives winter or summer

rain. If the natural precipitation is of the order of 500 mm annually,

about 200 litres should be supplied to each tree twice a month. A more

detailed analysis can be undertaken with an irrigation specialist who

can evaluate specific situations.

Pruning and Training of Olive Trees

Although

old olive groves have well established trees bearing excellent crops,

they are of lower tree densities and trees more than likely have

multiple trunks. This combination is labour intensive and quite

unsuitable for modern groves.

With new plantings it is essential

to provide them with proper care. Very little pruning is undertaken

with young trees so that they will bear as quickly as possible. Newly

planted olive trees should be trained in either the free form vase

shape or the monoconical shape. In both cases it is essential that a

single trunk is established. This can be achieved by removing laterals

at convenient times leaving a single trunk, about one metre in height.

The free vase form is better for hand picking whereas the monocone is

more suited to machine harvesting.

For the free form vase shape,

3 to 5 lateral shoots are selected to provide the scaffold branches.

Tree growth is promoted to follow the scaffold, thinning the internal

growth to allow light penetration and hence better cropping. The

monoconical shape is developed by training the main axis of the trunk

as the leader. Here a stout stake is important to keep the leader

erect. Laterals are trained to grow out from the leader in a lateral

fashion. Such training is undertaken in the first years after planting.

After that only light targeted pruning is required. The crown of the

monoconical shape, which is believed to have a larger fruiting surface,

develops quickly and upward. The latter aspect could be an advantage in

more intensive plantings. The economics of the two pruning methods have

yet to be revealed. One thing for sure, proper training reduces the

need for more radical pruning later!

Trees pruned in the ways

described above have smaller crown volumes than untrained trees and so

can take advantage of the available light, particularly with closer

plantings. Such training allows for the development of a strong

branching scaffold which can cope with heavy cropping as well as

providing an efficient system for mechanical harvesting. Another

advantage is that fruit bearing is brought on earlier.

Olive

trees need some pruning every 2-3 years. The objectives of pruning are

to remove suckers from the base, dead wood and excessive internal

growth to admit more light into the crown of the tree to improve fruit

quality. Excessive pruning particularly from the periphery of crown can

result in loss of new wood, lower yields and possible sunburn damage.

An- other advantage in reducing dense foliage is that it lowers the

risk of insect infestations and disease.

Old trees can be

rejuvenated by cutting back to either the scaffold branches near to the

trunk or to the main trunk itself. In old groves a cycle of heavy

pruning over 6-8 years will result in the development of "young"

healthy trees bearing commercial quantities of olives. Grafting on new

varieties is also possible with such radical pruning procedures.

Research needs to be undertaken to develop and evaluate machine assisted pruning methods.

Fertilisation

Both

in Australia and in Europe applications of superphosphate, nitrogen,

potassium, animal manures and mulching agents have a positive effect on

the yield of olive trees. Nitrogen is the most important nutrient being

required for new shoot growth and flower set. Soil and leaf analysis

can be used to guide the fertilisation process. A typical application

for mature trees is about 4 kg of 17:7:9 NPK. For dryland groves 75% is

applied any time between April and July with the balance in spring.

With irrigated groves, the nitrogen can be divided into three

applications, 50% in April and 25% each in January and September. If

required, phosphate and potassium are generally applied in spring at

rates per tree of up to 0.5 kg for phosphorous and 1 kg for potassium.

In Australia 3-5 yearly applications of superphosphate are usually

sufficient. Foliar sprays of urea and boron are also useful.

Diseases, Infestations and Pests

There

appear to be less problems with disease in olive trees growing in

Australia than in Europe. This could be a function of the low levels of

olive activity in Australia and the strict national and international

quarantine controls that are practised. Even so scale infestations,

black scale (

Saissetia oleae) and olive scale (

Parlaturia oleae),

parasitise the carbohydrate supply of olives reducing the sugar content

and increasing the acidity of fruit. Infected trees have visible scale

and fungus, the latter growing on the honeydew excreted by the scale.

Fruits are deformed and leaf drop occurs. Olive lace bug (

Froggattia olivinia) also extracts carbohydrates from the leaves and hence debilitates the tree.

Another

common pest is the nocturnally destructive black vine beetle which

lives in the soil during the day and moves onto the olive leaves at

night. Evidence of its effect is the characteristic chewed margins of

the leaves.

Fungal infestations can destroy total olive crops. Although not as widespread as scale, anthracnose (

Gloeosporium olivarum)

infection is most destructive. Infection sets into young fruit and

evidence of the disease is not apparent until the fruit ripens where

soft rot develops from the sides and tips of the fruit. Olive leaf spot

or peacock spot caused by the fungus

Spilocea oleaginea

is less common in Australia. Signs include dark round lesions on leaves

causing premature leaf drop and damage to young wood. Productivity of

affected olive trees is reduced. Other fungi such as

Verticillium and

Phythopthora can be devastating to olive trees.

Bacterial

and nematode infections are not a major problem at this point of time

in Australian olive groves. Birds and animals are a problem

particularly where natural food sources have been lost to development

and agricultural activities. A variety of birds damage or eat the

olives, damage young shoots and hence reduce productivity. Land-grazing

animals, indigenous, feral or farmed can cause physical damage, eat the

growing shoots and ringbark the olive trees.

Orchard hygiene and

careful attention underlie the management of all the above problems.

Ensuring clean surrounds, removal of damaged fruit that can harbour

infection and removal of diseased parts of plants is the basis of

disease control. Mulching with straw and ensuring branches do not have

contact with the ground is vitally important. A second strategy is the

application of appropriate 'cidal' agents. Here care must be taken that

the agents have been approved for use in olives. More research needs to

be undertaken to determine herbicide and pesticide residue levels in

olive fruit and olive oil. When using sprays there is always the risk

that natural predators may also be killed causing further unexpected

problems.

Olive Harvesting

Traditionally

olives have been picked by hand. With increasing labour costs, methods

such as machine harvesting with tree shakers, suitable for most

cultivars has become popular. Hand picking is adequate for small

groves, however proves to be impractical and too expensive in

commercial groves. A major advantage of hand-picking is that the fruit

is less likely to bruise resulting in better presentation for the fresh

fruit and table olive market. For machine harvesting, olives must be of

a weight that it will dislodge on shaking. The Koroneiki olive cultivar

originating from Greece, produces one of the best commercially

available extra virgin oils, however it is too small (1-2 grams) to

pick with a tree shaker. New growing methods with olive trees as

hedge-rows and picking technologies similar to those used for grape

picking need to be perfected to allow for more efficient olive

production. Bruised olives and olives that have fallen naturally from

trees are likely to produce oils that will not meet the olive oil

purity and quality tests such as free acid and organoleptic tests

because of increased likelihood of fermentation.

Olive cultivar

selection is not only important for harvesting method but also in

relation to fruit maturation. Cultivars will mature at different times

during the season, which can be advantageous for hand picking, however

when the groves are to be picked over a relative small period of time

then an appropriate maturation index needs to be determined. A rule of

thumb method is to pick when the crop characteristics are about one

quarter green ripe, one quarter are black ripe and the reminder of the

crop is half ripe. Green ripe olives will produce a green fruity oil

whereas black ripe olives yield a yellow sweeter oil.

Depending

on the cultivar and degree of ripeness, olives are picked between

autumn and spring. Table olives are picked in the early to mid part of

the period whereas oil olives can be picked in a later part of the

period.

Post Harvest Handling

Olives

should be processed as soon as possible and certainly within 3-4 days

after picking. Processing within the grove facilities, particularly for

table olive production is ideal and should be part of a vertical

integration plan. If the grower also produces the oil profitability

increases markedly. Olives must be handled carefully after picking

because of their low bruising resistance. Olives should not be left

standing around in bags, stacks or in trailers because of the risk of

fermentation and the development of off flavours. Storage life of

olives at 20°-30° C is only a few days after harvest, however storage

life increases when they are stored in a cold room. Olives are very

sensitive to deep freezing, temperatures, -15° to -5° C, however more

research needs to be undertaken as to the quality of oil from thawed

olives and the cost effectiveness of the process.

FoodstuffsOlive

fruit is a source of important foodstuffs, preserved table olives and

olive oil. Table olives are popular as part of the Mediterranean diet

and more recently an integral part of the take away pizza market. The

latter has been a major market for preserved olives in the United

States of America. To make olives edible the fruit flesh is modified by

fermentation, salt treatment or drying to remove the bitterness due to

polyphenolic compounds and in particular oleuropin. No toxicity to the

fruit is known, however poorly preserved fruit can result in food

poisoning such as botulism. Olive fruits are rich in oil and therefore

high in energy. They are a good source of protein and β-carotene and

contain other useful nutrients such as sugars, Vitamins B, C and E,

Iron and other minerals.

Consumer forms of preserved olives are

pickled green or black. Those prepared by the Spanish method are stored

in salt solution whereas Greek style olives can have vinegar and added

olive oil. Most commercially available black olives are artificially

coloured during processing using sodium hydroxide and iron salts. Dried

black olives and taponade are also popular and can be easily prepared

domestically and commercially. The latter is a paste containing

preserved olive flesh, anchovies and capers. Every country that is in

the olive business believes that their olives are the best!

Olive OilOlive

oil is obtained by pressing or centrifuging the crushed fruit including

the seed. All olive oils obtained from olives are classified as Virgin

Olive Oils with the highest quality being Extra Virgin Olive Oil. This

has an acid value of less than 1 % and an organoleptic rating of

greater than 6.5. Olive oils marketed as pure olive oil, although very

popular with consumers, are generally poorer in quality than Virgin

Olive Oils. They are processed from poor quality olive oil to remove

impurities and off flavours. Olive Pomace Oil is made up of solvent

extracted oil from the pomace remaining after pressing the crushed

olives for Virgin Olive Oil production. Olive oils, particularly the

virgin olive oils. are high in monounsaturated fats, Vitamin E,

polyphenols and aromatic compounds. The price of olive oil has

fluctuated aver the past few years, but there is a general upward trend.

Margarine

containing 30% olive oil is now available in Australia. Although

Australian growers have claimed that they will aim for the virgin olive

oil market, this will only account for 25-30% of the Australian olive

oil. The bulk of the olive oil will need to be directed to the

supermarket shelf and to the food services industry. This will

necessitate the development of olive oil refining facilities capable of

producing consumer acceptable olive oil from lesser quality olive oils.

Animal FeedThe fruit, leaves, and pomace are valuable as supplementary feed for animals, goats, sheep, fowl and others.

More

research is required to develop technologies to improve the feed value

from parts of the olive tree. Animals can forage under the trees eating

olives that have fallen to the ground. Olive pomace spread around the

orchard also provides food for forage. The latter has value because of

the protein and residual oil content. A problem in using pomace is that

the crushed fruit contains both flesh and the poorly digestible woody

pit. Current international research is focused around improving the

availability of the fatty acids and breaking down the woody pit to

improve digestibility. Animals find the olive leaves palatable and have

no aversion to eating them from prunings and parts of the tree that can

be easily reached. Methods for improving the nitrogen content of olive

leaves are being investigated.

Compost and FuelOlive

waste products have the potential for making compost or using them as

mulching agents. Traditionally the pomace from oil making is spread

around the grove providing valuable organic matter. Having the oil

making facilities at the grove site allows the grower to take advantage

of this valuable waste product. Where oil-making is associated with a

larger centralised operation, the olive pomace needs to be disposed of

in an environmentally acceptable manner. One process involves the

solvent extraction of residual oil from the pomace, about 5%, which is

then used to make olive pomace oil or used for technical grade oil for

industrial or consumer directed products such as soaps. The olive

pomace can also be incorporated into garden products by commercial

compost producers. Because of its significant oil content, the pomace

can be used as a fuel in the olive oil making plant or be pressed into

blocks for commercial sale.

Farm Site UsesThe

olive tree is a valuable shade tree for stock and for growing substory

crops. Traditional broadacre farmers are seriously considering using

olive trees as windbreaks and in alley farming practice. The olive tree

will be a valuable landcare alternative to eucalyptus and other

indigenous species. Being a long lived perennial, relatively

deep-rooted under rainfed conditions, it will improve soil integrity

and reduce soil erosion with the added advantage of providing a

potentially saleable crop.