From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Passionfruit

Passiflora

edulis Sims

PASSIFLORACEAE

Of the estimated 500 species of Passiflora, in the family

Passifloraceae, only one, P. edulis Sims, has the exclusive designation

of passionfruit, without qualification. Within this species, there are

two distinct forms, the standard purple, and the yellow, distinguished

as P. edulis f. flavicarpa Deg., and differing not only in color but in

certain other features as will be noted further on.

General names for both in Spanish are granadilla, parcha, parchita,

parchita maracuyá, or ceibey (Cuba); in Portuguese, maracuja peroba; in

French, grenadille, or couzou. The purple form may be called purple,

red, or black granadilla, or, in Hawaii, lilikoi; in Jamaica, mountain

sweet cup; in Thailand, linmangkon. The yellow form is widely known as

yellow passionfruit; is called yellow lilikoi in Hawaii; golden

passionfruit in Australia; parcha amarilla in Venezuela.

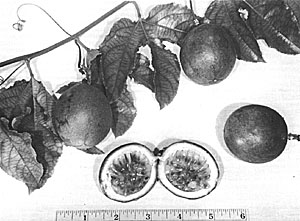

Fig. 91: Purple passionfruit (Passiflora

edulis) is subtropical, important in some countries, while

the more tropical yellow passionfruit excels in others. Both yield

delicious juice.

Description

The passionfruit vine is a shallow-rooted, woody, perennial, climbing

by means of tendrils. The alternate, evergreen leaves, deeply 3-lobed

when mature, are finely toothed, 3 to 8 in (7.5-20 cm) long, deep-green

and glossy above, paler and dull beneath, and, like the young stems and

tendrils, tinged with red or purple, especially in the yellow form. A

single, fragrant flower, 2 to 3 in (5-7.5 cm) wide, is borne at each

node on the new growth. The bloom, clasped by 3 large, green, leaflike

bracts, consists of 5 greenish-white sepals, 5 white petals, a

fringelike corona of straight, white-tipped rays, rich purple at the

base, also 5 stamens with large anthers, the ovary, and triple-branched

style forming a prominent central structure. The flower of the yellow

is the more showy, with more intense color. The nearly round or ovoid

fruit, 1 1/2 to 3 in (4-7.5 cm) wide, has a tough rind, smooth, waxy,

ranging in hue from dark-purple with faint, fine white specks, to

light-yellow or pumpkin-color. It is 1/8 in (3 mm) thick, adhering to a

1/4 in (6 mm) layer of white pith. Within is a cavity more or less

filled with an aromatic mass of double-walled, membranous sacs filled

with orange-colored, pulpy juice and as many as 250 small, hard,

dark-brown or black, pitted seeds. The flavor is appealing, musky,

guava-like, subacid to acid.

Origin and

Distribution

The purple passionfruit is native from southern Brazil through Paraguay

to northern Argentina. It has been stated that the yellow form is of

unknown origin, or perhaps native to the Amazon region of Brazil, or is

a hybrid between P. edulis and P. ligularis (q.v.). Cytological studies

have not borne out the hybrid theory. Speculation as to Australian

origin arose through the introduction of seeds from that country into

Hawaii and the mainland United States by E.N. Reasoner in 1923. Seeds

of a yellow-fruited form were sent from Argentina to the United States

Department of Agriculture in 1915 (S.P.I. No. 40852) with the

explanation that the vine was grown at the Guemes Agricultural

Experiment Station from seeds taken from fruits purchased in Covent

Garden, London. Some now think the yellow is a chance mutant that

occurred in Australia. However, E.P. Killip, in 1938, described P.

edulis in its natural range as having purple or yellow fruits.

Brazil has long had a well-established passionfruit industry with

large-scale juice extraction plants. The purple passionfruit is there

preferred for consuming fresh; the yellow for juice processing and the

making of preserves.

In Australia, the purple passionfruit was flourishing and partially

naturalized in coastal areas of Queensland before 1900. Its

cultivation, especially on abandoned banana plantations, attained great

importance and the crop was considered relatively disease-free and

easily managed. Then, about 1943, a widespread invasion of Fusarium

wilt killed the vines and forced the undertaking of research to find

fungus-resistant substitutes. It was discovered that the neglected

yellow passionfruit is both wilt-and nematode-resistant and does not

sucker from the roots. It was adopted as a rootstock and plants

propagated by grafting were soon made available to planters in

Queensland and northern New South Wales.

The Australian taste is strongly prejudiced in favor of the purple

passionfruit and growers have been reluctant to relinquish it

altogether. Only in the last few decades have they begun to adopt

hybrids of the purple and yellow which have shown some ability to

withstand the serious virus disease called "woodiness".

New Zealand, in the early 1930's, had a small but thriving purple

passionfruit industry in Auckland Province but in a few years the

disease-susceptibility of this type brought about its decline. Good

local marketing and export prospects have brought about a revival of

efforts to control infestations and increase acreage, mostly in the Bay

of Plenty region. Today, fruits and juice are exported. A profitable

purple passionfruit industry has developed also in New Guinea.

In Hawaii, seeds of the purple passionfruit, brought from Australia,

were first planted in 1880 and the vine came to be popular in home

gardens. It quickly became naturalized in the lower forests and, by

1930, could be found wild on all the islands of the Hawaiian chain. In

the 1940's, a Mr. Haley attempted to market canned passionfruit juice

in a small way but the product was unsatisfactory and his effort was

terminated by World War II. A processor on Kauai produced a concentrate

in glass jars and this project, though small, proved successful. In

1951, when Hawaiian passionfruit plantings totalled less than 5 acres

(2 ha), the University of Hawai'i chose this fruit as the most promising

crop for development and undertook to create an industry based on

quick-frozen passionfruit juice concentrate. From among Mr. Haley's

vines, choice strains of yellow passionfruit were selected. These gave

four times the yield of the purple passionfruit and had a higher juice

content. By 1958, 1,200 acres (486 ha) were devoted to yellow

passionfruit production and the industry was firmly established on a

satisfactory economic level.

Commercial culture of purple passionfruit was begun in Kenya in 1933

and was expanded in 1960, when the crop was also introduced into Uganda

for commercial production. In both countries, the large plantations

were devastated several times by easily-spread diseases and pests. It

became necessary to abandon them in favor of small and isolated

plantings which could be better protected.

South Africa in 1947 produced 2,000 tons of purple passionfruit for

domestic consumption. Production was doubled by 1950. In 1965,

passionfruit plantations were initiated over large areas of the

Transvaal to meet the market demand and apparently there have been no

serious setbacks as yet, from disease or other causes.

India, for many years, has enjoyed a moderate harvest of purple

passionfruit in the Nilgiris in the south and in various parts of

northern India. In many areas, the vine has run wild. The yellow form

was unknown in India until just a few decades ago when it was

introduced from Ceylon and proved well adapted to low elevations around

Madras and Kerala.

It was quickly approved as having a more pronounced flavor than the

purple and producing within a year of planting heavier and more regular

crops.

The purple passionfruit was introduced into Israel from Australia early

in the 20th Century and is commonly grown in home gardens all around

the coastal plain, with small quantities being supplied to processing

factories.

Passionfruit vines are found wild and cultivated to some extent in many

other parts of the Old World–including the highlands of Java, Sumatra,

Malaya, Western Samoa, Norfolk Islands, Cook Islands, Solomon Islands,

Guam, the Philippines, the Ivory Coast, Zimbabwe and Taiwan. From

several of these sources, considerable quantities of yellow

passionfruit juice and pulp are exported to Australia, causing some

protests from Queensland growers. The yellow passionfruit was

introduced into Fiji from Hawaii in 1950, was distributed to farmers in

1960 and became the basis of a small juice-processing industry. Fiji

has exported to Australia, New Zealand, and Canada as well as to nearby

islands.

In South America, interest in yellow passionfruit culture intensified

in Colombia and Venezuela in the mid-1950's and in Surinam in 1975. In

Colombia, there are commercial plantations mainly in the Cauca Valley.

YELLOW PASSIONFRUIT, Passiflora

edulis var. flavicarpa

Since the introduction of the yellow

passionfruit from Brazil into Venezuela in 1954, it has achieved

industrial status and national popularity. Much effort is being devoted

to improving the yield to better meet the demand for the extracted

juice, passionfruit ice cream, and other appealing products such as

bottled passionfruit-and-rum cocktail.

The purple passionfruit was naturalized in the Blue Mountains of

Jamaica by 1913, and both the purple and the yellow are planted to some

extent in Puerto Rico.

Various species of Passiflora have reached the United States Plant

Introduction Station (now the Subtropical Horticulture Research Unit)

in Miami, Florida, in the routine course of plant accession. Some vines

were known to exist and bear fruit year after year here and there in

the southern and central areas of the state since 1887 or earlier. In

1953, I requested seeds of good strains of the purple and yellow forms

from the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Stock and gave seeds

to experimenters. In 1955, one yellow-fruited vine from these seeds was

flourishing at Pinecrest and, from the reports of hunters camping

beyond that locality, it appears that bird-transported seeds have

produced fruiting vines in outlying Everglades hammocks. In 1957, a

very fruitful specimen was thriving at the home of Benjamin Blumberg in

Coconut Grove, and an escape was bearing unusually large fruits in the

treetops of a natural hammock a few miles away.

At this time, the purple passionfruit was being grown successfully by a

homeowner further north, at Land O'Lakes, Pasco County, and the seeds

were advertised for sale. There were small plantations of purple

passionfruit in San Diego County, California, the fruits being sold on

the fresh fruit market and also processed for juice. However, there was

little interest in developing either form as a crop in the United

States. At the University of Florida's Subtropical Experiment Station

in Homestead, Florida, limited trials with the purple and yellow forms

resulted in words of discouragement, the purple vine in particular

having proved so susceptible to disease. Certain vines at the Plant

Introduction Station had died from Fusarium attack and the survivors

showed poor fruiting performance.

Dr. Robert Knight and Harold F. Winters of the United States Department

of Agriculture prepared two reports on the pollination of the yellow

passionfruit and the problems affecting yield. They expressed a dim

view of economical juice production and the need for extensive field

studies. They offered plant material to anyone qualified to undertake

such work. The Minute Maid Company established a test plot of the

yellow form at Indiantown in 1965. They found the fruit entirely

satisfactory for processing but abandoned the project 2 years later,

stating: "The yields are not as large as in more tropical areas where

the plant remains productive all year round. Our plants went out of

production during the winter season. During the windy spring months of

March and April, the vines are badly damaged and no flowers are set

until sometime in May. We also found that the passionfruit were

expensive to harvest. The fruit has to fall on the ground and sometimes

it gets hung up in the vines. There is a continual collection of small

quantities of fruit throughout the [bearing] year * Special equipment

is needed to obtain the juice from the fruit without bits of the calyx

showing up as objectionable black specks. This equipment is costly and

can only be justified when a large volume of fruit is being processed."

In 1965, the Laboratorie de Recherche des Produits Nestlé, Vevey,

Switzerland, placed the passionfruit among the three

insufficiently-known tropical fruits having the greatest potential for

nectar processing for the European market. It is obvious, then, that in

spite of the handicaps of passionfruit culture, the crop offers

revenue-earning opportunities for developing countries with low labor

costs.

YELLOW PASSIONFRUIT, Passiflora

edulis var. flavicarpa

Varieties

The yellow form has a more vigorous vine and generally larger fruit

than the purple, but the pulp of the purple is less acid, richer in

aroma and flavor, and has a higher proportion of juice-35-38%. The

purple form has black seeds, the yellow, brown seeds.

The following are some of the older cultivars as well as some of the

more recent:

'Australian Purple',

or 'Nelly Kelly'–a purple selection of mild, sweet flavor, grown in

Australia and Hawaii.

'Common Purple'–the

form growing naturalized in Hawaii; thick-skinned, with small seed

cavity, but of fine flavor and low acidity.

'Kapoho Selection'–a

cross of 'Sevcik' and other yellow strains in Hawaii. A heavy bearer of

large fruits but subject to brown rot; many fruits contain little or no

pulp and the juice has the off-flavor of 'Sevcik' though not as

pronounced.

'Pratt Hybrid'–apparently

a natural cross between the 'Common Purple' and a yellow strain;

subject to rot, but juice is of fine color and flavor, low in acid.

'Sevcik Selection'–a

golden form of the yellow selected in Hawaii; a heavy bearer, but

subject to brown rot and the juice has a peculiar woody flavor.

'University Round

Selection'–Hawaiian crosses of 'Waimanalo' and 'Yee'–fruit

smaller than 'Yee'; not as attractive but yields 10% more juice of very

good flavor.

'University Selection No.

B-74'–a Hawaiian hybrid between 'Pratt' and 'C-77',

usually yellow, occasionally with red tinges; resembles 'Waimanalo';

has good juice yield and very good flavor.

'Waimanalo Selection'–consists

of 4 strains: 'C-54', 'C-77', 'C-80', of similar size, shape, color and

very good flavor, and 'C-39' as pollinator.

'Yee Selection'–yellow,

round, very attractive, highly disease-resistant, but fruit has thick

rind and low yield of juice which is of very good flavor.

What may be a great improvement over any of the above is the cultivar

known as 'Noel's Special'. It is a yellow passionfruit selected in 1968

from open-pollinated seedlings of a vine discovered at an abandoned

farm on Hilo, Hawaii, by Noel Fujimoto in the early 1950's. The fruit

is round, averages 3.17 oz (90 g); the cavity is filled with

dark-orange pulp yielding 43 to 56% bright-orange, richly flavored

juice. The vine is vigorous, begins to bear in one year, and is

tolerant to brown spot. It produces 88% marketable fruit in a season–a

higher proportion than any other cultivar.

In 1967, two purple X yellow hybrids–'3-1' and '3-26', developed at the

Redlands Horticulture Research Station, Queensland, had nearly replaced

the purple passionfruit in commercial plantations on the coast of

southern Queensland and New South Wales. They have a longer fruiting

season than the purple, are high-yielding, with high pulp content, keep

very well, and meet with little market resistance. Australian breeders

continued to strive for a type that would have the needed

characteristics and reproduce true from seed. Hybrid '23-E' followed.

By 1981, hybrid '3-1' had succumbed to a new, more virulent strain of

"woodiness" virus and had to be abandoned. Other popular hybrids are

'Lacey' and 'Purple-gold'.

In early 1980, several purple passionfruit hybrids, all

insect-pollinated, were introduced into the island of Niue, as possible

substitutes for the yellow form cultivated commercially there for

export since 1955, with the view of eliminating the labor of

hand-pollination required by the yellow for top production. However,

the hybrids are more susceptible to mealybug infestation.

One New Zealand grower has exported purple passionfruits to the United

States under the trade name of 'Bali

Hai'.

Commercial cultivars of the purple form in Brazil include 'Ouropretano', 'Muico', 'Peroba', and 'Pintado'; of the

yellow form, 'Mirim'

or 'Redondo',

and 'Guassu'

or 'Grande'.

In the Cauca Valley of Colombia, the best-performing yellow

passionfruit is the 'Hawaiiana'.

Venezuelan growers favor the 'Hawaiiana', 'Brasilera amarilla', and the

purple-fruited 'Brasilera rosada'.

A highly promising hybrid, 'M-21471A' has been developed by Dr. R.J.

Knight at the United States Department of Agriculture's Subtropical

Horticulture Research Station, Miami. The fruit is maroon, weighs about

3 oz (85 g); is close to the purple parent in quality; is

self-compatible and resists soil-borne diseases like its yellow parent.

F1 hybrids may be reddish-purple with more conspicuous white dots than

on the purple parent, and sometimes there is a tinge of yellow in the

background. F2 hybrids show three variations of purple and are

difficult to distinguish from the purple parent.

Fig. 92: Flowers of the purple passionfruit are fragrant and lovely,

though those of the yellow are richer in color.

Pollination

Yellow passionfruit flowers are perfect but self-sterile. In controlled

pollination studies at the College of Agriculture of Jaboticabal, Sao

Paulo, Brazil, it was found that the yellow passionfruit has three

types of flowers according to the curvature of the style: TC (totally

curved), PC (partially curved), and SC (upright-styled). TC flowers are

most prevalent.

Carpenter bees (Xylocopa megaxylocopa frontalis and X. neoxylocopa)

efficiently pollinated TC and PC flowers. Honey bees (Apis mellifera

adansonii) were much less efficient. Wind is ineffective because of the

heaviness and stickiness of the pollen. SC flowers have fertile pollen

but do not set fruit. To assure the presence of carpenter bees, it is

wise to have decaying logs among the vines to provide nesting places.

Carpenter bees will not work the flowers if the nectary is wet. If rain

occurs in 1 1/2 hrs after pollination, there will be no fruit set, but

if 2 hrs pass before rain falls, it will have no detrimental effect. In

the absence of carpenter bees in Fiji, farmers cross-pollinate by hand,

treating 600 flowers an hour, with 70% fruit set and 60% of fruit

reaching maturity.

The purple form blooms in spring and early summer (July-November) in

Queensland and again for a shorter period in fall and early winter

(February-April). In Florida, blooming occurs from mid-March through

April. The flowers open early in the morning (about dawn) and close

before noon, and are self-compatible. The yellow form has one flowering

season in Queensland (October-June). In Florida, blooming has occurred

from mid-April to mid-November. The flowers open around noon and close

about 9 to 10 PM and are self-incompatible.

In crossing the yellow and purple forms, it is necessary to

use the purple as the seed parent because the flowers of the yellow are

not receptive to the pollen of the purple, and an early-blooming yellow

must be utilized in order to have a sufficient overlapping period for

pollen transfer. Dr. R.J. Knight has suggested lengthening the overlap

by exposing the yellow to artificial light for 6 weeks before the

normal flowering season. However, despite the seasonal and hourly

differences, natural hybrids between the two forms occur in South

Africa, Queensland and in Hawaii. Growers of purple passionfruit in

South Africa are warned not to take seed from any vine in proximity to

a planting of yellow passionfruit, otherwise the seedlings are apt to

produce hybrid fruit of inferior quality.

In some areas, trellis-grown vines of the yellow passionfruit require

hand-pollination to assist fruit set. In the home garden, at least two

vines of different parentage should be planted and allowed to

intertwine for cross-pollination.

Climate

The purple passionfruit is subtropical. It grows and produces well

between altitudes of 2,000 and 4,000 ft (650-1,300 m) in India. In

Java, it grows well in lowlands but will flower and fruit only above

3,200 ft (1,000 m). In west-central Florida, at 28º N latitude and

slightly above sea-level, 3-year-old vines have survived freezing

temperatures with the lower 3 ft (.9 m) of the stems wrapped in

fiberglass 4 in (10 cm) thick. The upper parts suffered cold injury,

were cut back, the vines were heavily fertilized, recovered rapidly and

fruited heavily the second summer thereafter.

The yellow passionfruit is tropical or near-tropical. In Western Samoa,

it is grown from near sea-level up to an elevation of 2,000 ft (600 m).

Both forms need protection from wind. Generally, annual rainfall should

be at least 35 in (90 cm), but in the Northern Transvaal, in South

Africa, there is reduced transpiration because of high atmospheric

humidity and commercial culture is carried on with precipitation of

only 24 in (60 cm). It is reported that annual rainfall in

passionfruit-growing areas of India ranges between 40 and 100 in

(100-250 cm).

Soil

Passionfruit vines are grown on many soil types but light to heavy

sandy loams, of medium texture are most suitable, and pH should be from

6.5 to 7.5. If the soil is too acid, lime must be applied. Good

drainage is essential to minimize the incidence of collar rot.

Propagation

Passionfruit vines are usually grown from seeds. With the yellow form,

seedling variation provides cross-pollination and helps overcome the

problem of self-sterility. Some say that the fruits should be stored

for a week or two to allow them to shrivel and become perfectly ripe

before seeds are extracted. If planted soon after removal from the

fruit, seeds will germinate in 2 to 3 weeks. Cleaned and stored seeds

have a lower and slower rate of germination. Sprouting may be hastened

by allowing the pulp to ferment for a few days before separating the

seeds, or by chipping the seeds or rubbing them with fine sandpaper.

Soaking, often recommended, has not proved helpful. Seeds are planted

1/2 in (1.25 cm) deep in beds, and seedlings may be transplanted when

10 in (25 cm) high. If taller–up to 3 ft (.9 in)–the tops should be cut

back and the plants heavily watered.

Some growers prefer layers or cuttings of matured wood with 3 to 4

nodes. Cuttings should be well rooted and ready for setting out in 90

days. Rooting may be hastened by hormone treatment. Grafting is an

important means of perpetuating hybrids and reducing nematode damage

and diseases by utilizing the resistant yellow passionfruit rootstock.

If seeds are available in the early spring, seedlings for rootstocks

can be raised 4 in (10 cm) apart in rows 24 in (60 cm) apart and the

grafted plants will be ready to set out in late summer. If seeds cannot

be obtained until late summer, the seedlings are raised and grafted in

pots and set out in the spring. Scions from healthy young vines are

preferred to those from mature plants. The diameter of the selected

scion should match that of the rootstock. Either a cleft graft, whip

graft, or side-wedge graft may be made.

If approach-grafting is to be done, a row of potted scions must be

placed close alongside the row of rootstocks so that the union can be

made at about 3/4 of the height of the plant.

Culture

Root-pruning should precede transplanting of seedlings by 2 weeks.

Transplanting is best done on a cool, overcast day. The soil should be

prepared and enriched organically a month in advance if possible.

Grafted vines must be planted with the union well above ground, not

covered by soil or mulch, otherwise the disease resistance will be

lost. Mounding of the rows greatly facilitates fruit collection.

In plantations, the vines are set at various distances, but studies in

Venezuela indicate that highest yields in yellow passionfruit are

obtained when the vines are set 10 ft (3 m) apart each way. In South

Africa, purple passionfruit vines are set 8 ft (2 1/2 m) apart in cool

areas, and 12 to 15 ft (3 1/2-4 1/2 m) apart in warm areas. Spacing of

purple passionfruit in Kenya has been 10 ft (3 m) between vines and 6

ft (1.8 m) between rows. Recent 3-year trials of 4 ft (1.2 m) between

rows, with light pruning the 2nd and 3rd years, resulted in the highest

yield (50% of the crop being home the first year). But it is recognized

that such close planting can lead to disease problems and replanting

after the 3rd year.

Commercially, vines are trained to strongly-supported wire trellises at

least 7 ft (2.13 m) high. However, for the benefit of the homeowner, it

should be pointed out that the yellow passionfruit is more productive

and less subject to pests and diseases if allowed to climb a tall tree.

After a vine of either the yellow or purple passionfruit attains 2

years of age, pruning once a year will stimulate new growth and

consequently more flower and fruit production. The average life of a

plantation in Fiji is only 3 years. Judicious pruning of lateral

branches after fruiting aids in disease control and can extend

plantation life to 5 or 6 years. In South Africa, at elevations between

4,000 and 4,800 ft (1,200-1,460 m), plantations are kept in full

production for as long as 8 years.

Regular watering will keep a vine flowering and fruiting almost

continuously. Least flowers develop during the winter season due to

short day length. Water requirement is high when fruits are approaching

maturity. If soil is dry, fruits may shrivel and fall prematurely.

Fertilizer (10-5-20 NPK) should be applied at the rate of 3 lbs (1.36

kg) per plant 4 times a year, under normal conditions. In India, trials

of purple passionfruit on red sandy loam with a pH of 6.5 and high

organic content, the optimum fertilizer treatment was found to be 290

lbs (132 kg) N and 69 1/2 lbs (31.6 kg) P per ha per year.

French horticulturists have reported that, in plantations on the Ivory

Coast, annual supplements of 8 oz (220 g) urea and 7 1/2 oz (210 g)

potassium sulfate per plant per year of age will have a highly

favorable effect on production. It is said that 32 to 36 oz (900-1,000

g) of nitrogen are required to produce 66 lbs (30 kg) of fruits, but

excessive nitrogen will cause premature fruit drop. Passionfruit vines

should always be watched for deficiencies, particularly in potassium

and calcium, and of less importance, magnesium.

The passionfruit vine, especially the yellow, is fast-growing and will

begin to bear in 1 to 3 years. Ripening occurs 70 to 80 days after

pollination. Injuries to the base of the vine, which allow entrance of

disease organisms, can be avoided by hand-weeding or the application of

herbicides around the main stems. These practices will also protect the

shallow root system. In Surinam, good weed control under trellises has

been achieved by covering the soil with black plastic.

Seasons and

Harvesting

The different flowering seasons of the purple and yellow passionfruits

have been mentioned under "Pollination". In some areas, as in India,

the vines bear throughout the year but peak periods are, first, August

to December, and, second, March to May. At the latter time, the fruits

are somewhat smaller, with less juice. In Hawaii, passionfruits mature

from June through January, with heaviest crops in July and August and

October and November. With variations according to cultivar, and with

commercial cultivation both above and below the Equator, there need

never be a shortage of raw material for processing.

Ripe fruits fall to the ground and will roll in between mounded rows.

They do not attract flies or ants but should be collected daily to

avoid spoilage from soil organisms. In South Africa, they are subject

to sunburn damage on the ground and, for that reason, are picked from

the vines 2 or 3 times a week in the summertime before they are fully

ripe, that is, when they are light-purple. At this stage, they will

reach the fresh fruit market before they wrinkle. In winter, only one

picking per week is necessary. For juice processing, the fruit is

allowed to attain a deep-purple color. In India and Israel the fruits

are always picked from the vine rather than being allowed to fall. It

has been found that fallen fruits are lower in soluble solids, sugar

content, acidity and ascorbic acid content.

The fruits should be collected in lugs or boxes, not in bags which will

cause "sweating". If not sent immediately to processing plants, the

fruits should be spread out on wire racks where there will be good air

circulation.

Yield

Many factors influence the yield of passionfruit vines. In general,

yields of commercial plantations range from 20,000 to 35,000 lbs per

acre (roughly the same number of kg per ha). In Fiji, with hand

pollination, 173 acres (70 ha) will yield 33 tons (30 MT) of fruits.

Hybrids in Australia have raised yields far beyond those obtained with

the purple passionfruit.

On the average, a bushel of passionfruits in Australia weighs 36 lbs

(16 kg); yields 13 1/3 lbs (6 kg) of pulp from which is obtained 1 gal

(3.785 liters)–that is 10.7 lbs (4.5 kg) of juice, and 2.6 lbs (1.18

kg) of seeds. With some strains, the juice yield is much higher.

Storage

Underripe yellow passionfruits can be ripened and stored at 68º F (20º

C) with relative humidity of 85 to 90%. Ripening is too rapid at 86º F

(30º C). Ripe fruits keep for one week at 36º to 45º F (2.22º-7.22º C).

Fruits stored in unperforated, sealed, polyethylene bags at 74º F

(23.1º C), have remained in good condition for 2 weeks. Coating with

paraffin and storing at 41º to 44.6º F (5º to 7º C) and relative

humidity of 85 to 90%, has prevented wrinkling and preserved quality

for 30 days.

Pests and

Diseases

In Hawaii and Australia, infestations of the passion vine mite

(Brevipalpus phoenicis) occur during dry weather in the warm season,

defoliate the younger portions of the vines but not the terminus, and

make brown blemishes on the fruits. The passion vine bug (Leptoglossus

australis) feeds on flowers and young, green fruits in Queensland. The

green vegetable bug, or stinkbug, (Nezara viridula) is a similar but

lesser menace to the plant and young fruits. Both the immature and the

adult stages suck the sap of the growing tips, as do the brown stinkbug

(Boerias maculata), the large black stinkbug (Anoplocnemis sp.) and the

small black stinkbug (Leptoglossus membranaceus).

In Florida, the yellow passionfruit is commonly found to be

superficially punctured by a stinkbug (Chrondrocera laticornis),

affecting only its appearance. Thrips (Thysanoptera sp.) injure and

cause stunting of young seedlings in nurseries. In dry weather, they

also feed on leaves and fruits, leaving them defaced and prone to

shrivel and fall prematurely. In East Africa, injury from the tobacco

white fly (Bemisia tabaci) may lead to galls on the leaves. Leaf

beetles (Haltica sp.) and weevils (Systates spp.) chew the foliage, and

cutworms behead seedlings in nurseries. Two lepidopterous pests, Dione,

or Agraulis, vanillae and Mechanitis variabilis are common in Colombia.

Among scales attacking the vine and petioles, white peach scale

(Pseudaulacaspis pentagona) is most troublesome in Queensland. Not as

prevalent are round purple scale (Chrysomphalus ficus) and granadilla

purple scale (Parasaissetia nigra). These pests may cause dieback of

the entire plant if not controlled. Red scale (Aonidiella aurantii) is

common on mature passion vines in Queensland. Soft brown scale (Coccus

hesperidum) is occasionally troublesome. The passion vine leaf hopper

(Scolypopa australis) requires protective measures. The citrus mealybug

(Planococcus citri) is a major Queensland pest in summer. Spraying,

unfortunately, kills its chief predator, the mealybug ladybird,

Cryptolaemus montrouzieri. The aphids, Aphis gossypii and Myzus

Persicae, transmit the virus which causes "woodiness" (see below).

There has been no report of attack by the Caribbean fruit fly

(Anastrepha suspensa) in Florida, though Anastrepha infestation was on

one occasion observed by Curtis Dowling in Passflora fruits in Costa

Rica. In Brazil, fruit flies of the genus Anastrepha, and in Hawaii the

Oriental fruit fly and the melon fly, deposit eggs in the very young,

tender fruits. In these, the larvae seem able to develop and cause the

immature fruits to shrivel and fall. If fruits are punctured when

nearly mature, the only effect is an external scar. The same is

reported concerning the dominant Queensland fruit fly (Dacus tryoni)

and the less common Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) in

Australia.

In South Africa, purple passionfruit vines are damaged by several

species of nematodes. The most important, which causes extreme

thickening of the roots, is the root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne

javanica. Others include the spiral nematode (Scutellonema truncatum

and Helicotylenchus sp.), and the lesion nematode (Pratylenchus sp.).

The yellow passionfruit is nematode-resistant.

The main diseases of purple passion fruit in Australia are brown spot,

Septoria spot and base rot, Phytophthora blight, Fusarium wilt,

woodiness, and damping-off. Brown spot, caused by Alternaria

passiflorae in warm weather, is a major affliction of the purple

passionfruit also in New Zealand and East Africa. In Hawaii, brown spot

is the leading disease of the yellow passionfruit and A. tenuis was

found to be the dominant species associated with the disease in 1969.

A. macrospora has occasioned severe leaf spot and branch lesions in

India. A similar disease causing spotting and crinkling of leaves and

fruit first appeared in Ceylon in 1970. Septoria spot, from the fungus

Septoria passiflorae, most common in summer and fall, is evidenced by

more numerous and smaller spots than brown spot, on all parts of the

vine and on the fruits, and it is spread by rain, dew and overhead

irrigation. Some believe this fungus to be also the source of base rot,

often induced by injury from mowers or other mechanical equipment.

Phytophthora cinnamoni, the source of collar rot in Fiji, makes it

necessary to replace yellow passionfruit plantings there every 30 to 35

months. P. nicotinae var. parasitica has been linked to fatal blight,

or stem rot, and fruit rot in purple passionfruit vine, but not in the

yellow, in wet periods of summer and fall in Queensland and South

Africa. P. cinnamoni and P. nicotinae are responsible for root rot in

New Zealand and Western Australia, and the latter is identified with

wilt in South Africa and Sarawak, and with damping-off and leaf blight

in both the purple and the yellow passionfruits in India.

Fusarium wilt, arising from the soil-borne fungus, Fusarium oxysporium

f. sp. passiflorae, can be reduced only by grafting the purple, or,

better still, purple-yellow hybrids, onto the Fusarium-resistant yellow

passionfruit rootstock. However, Bedoya et al. have reported that, in

the zones of Palmira, Cerrito and Ginebra of the Cauca Valley of

Colombia, but not in the zone of Unión, collar rot limits the life of

yellow passionfruit plantations to 3 years, and they found, in

inoculation experiments, that Fusarium solani produced the symptoms.

The first signs are chlorosis, necrosis and defoliation; next there is

splitting of the trunk and separation of the bark. The root becomes

progressively discolored and red rays extend to the surface of the soil.

Nectria haematococca, or Hypomyces solani, the ascogenous state of

Fusarium solani, has been determined to be the organism girdling the

collar zone and bringing on sudden wilt of the purple passionfruit vine

in Uganda.

The virus disease, "woodiness", or "bullet", appearing as small

misshapen fruits with thick rind and small pulp cavity, has been the

most serious plague of the purple passionfruit in Australia and East

Africa, but it has little effect on the yellow form. The "woodiness"

virus (PWV) is also the source of tip blight in the coastal districts

of central Queensland. This virus has a wide host range, not only in

the genus Passiflora, but also weedy species in the families

Amaranthaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Cucurbitaceae and Solanaceae.

There are a number of different strains of the "woodiness" virus. For

many years, inoculation of passionfruit vines with mild strains

protected them from further infection, and commercial hybrids

containing small doses of mild strains were released to farmers. But,

in 1978, a new, more virulent, strain of virus appeared and overcame

the "mild strain protection". The New South Wales Passionfruit Growers

Association, in response to this new threat, established, in 1979, a

Passionfruit Scion Accreditation Scheme to "improve the quality of

planting material by field selection and provide scionwood free of the

severe strain of woodiness virus", for a standard fee. Generally, 100

scions can be taken from each accredited vine in a season. By 1981,

16,000 scions had been supplied to commercial growers.

In 1973, two mosaic viruses–PPMV-K and PFMVMY–said to differ from other

reported Passiflora viruses, were found to be prevalent in commercial

plantings of the yellow passionfruit in the Bantung district of

Selangor, Malaya. Damping-off is caused by Rhizoctonia solani and

Pythium spp. in Queensland. Thread blight of yellow passionfruit vine

in Fiji and Western Samoa, seen as patches of black, papery, shredded

leaves with gray to tan layer of merged "threads" beneath, has been

attributed to Rhizoctonia solani (also called Thanatephorus cucumeris).

It may invade the entire vine.

Food Uses

The fruit is of easy preparation. One needs only cut it in half

lengthwise and scoop out the seedy pulp with a spoon. For home use,

Australians do not trouble to remove the seeds but eat the pulp with

cream and sugar or use it in fruit salads or in beverages, seeds and

all. Elsewhere it is usually squeezed through two thicknesses of

cheesecloth or pressed through a strainer to remove the seeds.

Mechanical extractors are, of course, used industrially. The resulting

rich juice, which has been called a natural concentrate, can be

sweetened and diluted with water or other juices (especially orange or

pineapple), to make cold drinks. In South Africa, passionfruit juice is

blended with milk and an alginate; in Australia the pulp is added to

yogurt. After primary juice extraction, some processors employ an

enzymatic process to obtain supplementary "secondary" juice from the

double juice sacs surrounding each seed. The high starch content of the

juice gives it exceptional viscosity. To produce a freeflowing

concentrate, it is desirable to remove the starch by centrifugal

separation in the processing operation.

Passionfruit juice can be boiled down to a sirup which is used in

making sauce, gelatin desserts, candy, ice cream, sherbet, cake icing,

cake filling, meringue or chiffon pie, cold fruit soup, or in

cocktails. The seeded pulp is made into jelly or is combined with

pineapple or tomato in making jam. The flavor of passionfruit juice is

impaired by heat preservation unless it is done by agitated or "spin"

pasteurization in the can. The frozen juice can be kept without

deterioration for 1 year at 0º F (-17.78º C) and is a very appealing

product. The juice can also be "vacuum-puff" dried or freeze-dried.

Swiss processors have marketed a passionfruit-based soft drink called

"Passaia" for a number of years in Western Europe. Costa Rica produces

a wine sold as "Parchita Seco."

Food

Value Per 100 g of Edible Portion

(Purple passionfruit, pulp and seeds)* |

| Calories |

90 |

| Moisture |

75.1

g |

| Protein |

2.2

g |

| Fat

|

0.7

g |

| Carbohydrates |

21.2

g |

| Fiber |

? |

| Ash

|

0.8g |

| Calcium |

13

mg |

| Phosphorus |

64

mg |

| Iron

|

1.6

mg |

| Sodium |

28

mg |

| Potassium |

348

mg |

| Vitamin

A |

700

I.U. |

| Thiamine |

Trace |

| Riboflavin |

0.13

mg |

| Niacin |

1.5

mg |

| Ascorbic

Acid |

30

mg |

*According to U.S. Dept. Agr., ARS. |

|

The yellow passionfruit has somewhat less ascorbic acid than the purple

but is richer in total acid (mainly citric) and in carotene content. It

is an excellent source of niacin and a good source of riboflavin. Free

amino acids in purple passionfruit juice are: arginine, aspartic acid,

glycine, leucine, lysine, proline, threonine, tyrosine and valine.

Carotenoids in the purple form constitute 1.160%; in the yellow,

0.058%; flavonoids in the purple, 1.060%; in the yellow, 1.000%;

alkaloids in the purple, 0.012%; in the yellow, 0.700% (mainly harman),

and the juice is slightly sedative. Starch content of purple

passionfruit juice is 0.74%; of the yellow, 0.06%.

Toxicity

A cyanogenic glycoside is found in the pulp of passionfruits at all

stages of development, but is highest in very young, unripe fruits and

lowest in fallen, wrinkled fruits, the level in the latter being so low

that it is of no toxicological significance.

Other Uses

Commercial processing of the yellow passionfruit yields 36% juice, 51%

rinds, and 11% seeds.

Rind:

The rinds have a very low pectin content–only 2.4% (14% on a dry weight

basis). Nevertheless, it has been determined in Fiji that extraction of

pectin from the rinds–up to 5 tons (4.5 MT) annually–reduces the

otherwise burdensome problem of waste disposal. The rind residue

contains about 5 to 6% protein and could be used as a filler in poultry

and stock feed. In Brazil, pectin is extracted from the purple form

which has a better quality pectin than that in the yellow. In Hawaii,

the pectin is not extracted. Instead, the rinds are chopped, dried, and

combined with molasses as cattle or pig feed. They can also be

converted into silage.

Seeds:

The seeds yield 23% oil which is similar to sunflower and soybean oil

and accordingly has edible as well as industrial uses. Up to 3,400

gallons (13,000 liters) can be obtained per year in Fiji. The seed meal

contains about 12% protein and 50 to 55% fiber. It has been judged

unsuitable for cattle feed.

Analyses of the fresh rind show: moisture, 78.43-85.24%; crude protein,

2.04-2.84%; fat, 0.05-0.16%; crude starch, 0.75-1.36%; sugars (sucrose,

glucose, fructose), 1.64%; crude fiber, 4.57-7.13%; phosphorus,

0.03-0.06%; silica, 0.01-0.04%; potassium, 0.60-0.78 %; organic acids

(citric and malic), 0.15%; ascorbic acid, 78.3-166.2%. The outer skin

of the purple form contains 1.4 mg per 100 g of the anthocyanin

pigment, pelargonidin 3-diglucoside. There is also some tannin.

The composition of the air-dried seeds is reported as: moisture, 5.4%;

fat, 23.8%; crude fiber, 53.7%; protein, 11.1%; N-free extract, 5.1%;

total ash, 1.84%; ash insoluble in HC1, 0.35%; calcium, 80 mg; iron, 18

mg; phosphorus, 640 mg per 100 g.

The seed oil contains 8.90% saturated fatty acids; 84.09% unsaturated

fatty acids. The fatty acids consist of: palmitic, 6.78%; stearic,

1.76%; arachidic, 0.34%; oleic, 19.0%; linoleic, 59.9%; linolenic, 5.4%.

Medicinal Uses:

There is currently a revival of interest in the pharmaceutical

industry, especially in Europe, in the use of the glycoside,

passiflorine, especially from P. incarnata L., as a sedative or

tranquilizer. Italian chemists have extracted passiflorine from the

air-dried leaves of P. edulis.

In Madeira, the juice of passionfruits is given as a digestive

stimulant and treatment for gastric cancer.

|

|