From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Pineapple

Ananas comosus

BROMELIACEAE

The pineapple is the leading edible member of the family

Bromeliaceae which embraces about 2,000 species, mostly epiphytic and

many strikingly ornamental. Now known botanically as Ananas comosus

Merr. (syns. A. sativus

Schult. f., Ananassa

sativa Lindl., Bromelia

ananas L., B.

comosa L.),

the fruit has acquired few vernacular names. It is widely called pina

by Spanish-speaking people, abacaxi in the Portuguese tongue, ananas by

the Dutch and French and the people of former French and Dutch

colonies; nanas in southern Asia and the East Indes. In China, it is

po-lo-mah; sometimes in Jamaica, sweet pine; in Guatemala often merely

"pine" .

Fig. 6: A spiny-leaved pineapple in the Supply garden, Homestead, Fla.,

1946.

Description

The

pineapple plant is a terrestrial herb 2 1/2 to 5 ft (.75-1.5 m) high

with a spread of 3 to 4 ft (.9-1.2 m); a very short, stout stem and a

rosette of waxy, straplike leaves, long-pointed, 20 to 72 in (50-180cm)

1ong; usually needle tipped and generally bearing sharp, upcurved

spines on the margins. The leaves may be all green or variously striped

with red, yellow or ivory down the middle or near the margins. At

blooming time, the stem elongates and enlarges near the apex and puts

forth a head of small purple or red flowers, each accompanied by a

single red, yellowish or green bract. The stem continues to grow and

acquires at its apex a compact tuft of stiff, short leaves called the

"crown" or "top". Occasionally a plant may bear 2 or 3 heads, or as

many as 12 fused together, instead of the normal one.

As

individual fruits develop from the flowers they join together forming a

cone shaped, compound, juicy, fleshy fruit to 12 in (30 cm) or more in

height, with the stem serving as the fibrous but fairly succulent core.

The tough, waxy rind, made up of hexagonal units, may be dark-green,

yellow, orange-yellow or reddish when the fruit is ripe. The flesh

ranges from nearly white to yellow. If the flowers are pollinated,

small, hard seeds may be present, but generally one finds only traces

of undeveloped seeds. Since hummingbirds are the principal pollinators,

these birds are prohibited in Hawaii to avoid the development of

undesired seeds. Offshoots, called "slips", emerge from the stem around

the base of the fruit and shoots grow in the axils of the leaves.

Suckers (aerial suckers) are shoots arising from the base of the plant

at ground level; those proceeding later from the stolons beneath the

soil are called basal suckers or "ratoons".

Origin and Distribution

Native

to southern Brazil and Paraguay (perhaps especially the Parana-Paraguay

River) area where wild relatives occur, the pineapple was apparently

domesticated by the Indians and carried by them up through South and

Central America to Mexico and the West Indies long before the arrival

of Europeans. Christopher Columbus and his shipmates saw the pineapple

for the first time on the island of Guadeloupe in 1493 and then again

in Panama in 1502. Caribbean Indians placed pineapples or pineapple

crowns outside the entrances to their dwellings as symbols of

friendship and hospitality. Europeans adopted the motif and the fruit

was represented in carvings over doorways in Spain, England, and later

in New England for many years. The plant has become naturalized in

Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras and Trinidad but the fruits of wild

plants are hardly edible.

Spaniards introduced the pineapple

into the Philippines and may have taken it to Hawaii and Guam early in

the 16th Century. The first sizeable plantation 5 acres (2

ha)—was established in Oahu in 1885. Portuguese traders are

said

to have taken seeds to India from the Moluccas in 1548, and they also

introduced the pineapple to the east and west coasts of Africa. The

plant was growing in China in 1594 and in South Africa about 1655. It

reached Europe in 1650 and fruits were being produced in Holland in

1686 but trials in England were not success ful until 1712. Greenhouse

culture flourished in England and France in the late 1700's. Captain

Cook planted pineapples on the Society Islands, Friendly Islands and

elsewhere in the South Pacific in 1777. Lutheran missionaries in

Brisbane, Australia, imported plants from India in 1838. A commercial

industry took form in 1924 and a modern canning plant was erected about

1946. The first plantings in Israel were made in 1938 when 200 plants

were brought from South Africa. In 1939, 1350 plants were imported from

the East Indies and Australia, but the climate is not a favorable one

for this crop.

Over the past 100 years, the pineapple has become

one of the leading commercial fruit crops of the tropics. In 1952-53,

world production was close to 1,500,000 tons and reportedly nearly

doubled during the next decade. Major producing areas are Hawaii,

Brazil, Malaysia, Taiwan, Mexico, the Philippines, South Africa and

Puerto Rico. By 1968, the total crop had risen to 3,600,000 tons, of

which only 100,000 tons were shipped fresh (mainly from Mexico, Brazil

and Puerto Rico) and925.000 tons were processed. In the period 1961-66,

imports of fresh pineapples into Europe rose by 70%. Soon many new

markets were opening. In 1973, the total crop was estimated at

4,000,000 tons with 2.2 million tons processed. The increased worldwide

demand for canned fruit has greatly stimulated plantings in Africa and

Latin America. For years, Hawaii supplied 70% of the world's canned

pineapple and 85% of canned pineapple juice, but labor costs have

shifted a large segment of the industry from Hawaii to the Philippines.

Because production costs in Hawaii (which are 50% labor) have increased

25% or more, Dole has transferred 75% of its operation to the

Philippines, where, in 1983, it employed 10,000 laborers on about

25,000, mostly rented, acres (10,117 ha).

Pineapples were first

canned in Malaya by a retired sailor in 1888 and exporting from

Singapore soon followed. By 1900, shipments reached a half million

cases. The industry alternately grew and declined, and then ceased

entirely for 3 1/2 years during World War II. The Malaysian Pineapple

Industry Board was established in 1959. Thereafter there has been

steady progress. The pineapple, was a very minor crop in Thailand until

1966 when the first large cannery was built. Others followed. Since

then processing and exporting have risen rapidly. In 1977-78 many

farmers switched from sugarcane to pineapple. Of the annual production

of 1 1/2 million tons, 1/8 is canned as fruit or Julce.

South

Africa produces 2.7 million cartons of canned pineapple yearly and

exports 2.4 million. In addition, 31,000 tons of fresh pineapple are

sold on the domestic market and 500,000 cartons exported yearly. As in

many areas, pineapple culture existed on a small scale on the Ivory

Coast until post WW II when cultural efforts were stepped up. By 1950,

annual production amounted to 1800 tons. By 1972, it had risen to

200,000 tons for shipment, fresh or canned, to western Europe.

Cameroun's annual production is about 6,000 tons.

In the Azores,

pineapples have been grown in green-houses for many years for export

mainly to Portugal and Madeira. They are of luxury quality, carefully

tended and blemish free, graded for uniform size and well padded in

each box for shipment.

As of 1971, the ten leading exporters of

fresh pineapples were (in descending order): Taiwan (39,621 tons),

Puerto Rico, Hawaii, Ivory Coast, Brazil, Guinea, Mexico, South Africa,

Philippines and Martinique (5,000 tons). The ten leading exporters of

processed pineapples were (in descending order): Hawaii, Philippines,

Taiwan, South Africa, Malaysia (Singapore), Ivory Coast, Australia,

Ryukyu, Mexico, Thailand (10,500,000 tons).

In Puerto Rico, the

pineapple is the leading fruit crop, 95% produced, processed and

marketed by the Puerto Rico Land Authority. The 1980 crop was 42,493

tons having a farm value of 6.8 million dollars.

For 250 years,

pineapples have been grown in the Bahama Islands. At one time plantings

on Eleuthera, Cat Island and Long Island totaled about 12,000 acres.

The pineapple was a pioneer crop along the east coast of Florida and

or, the Keys. In 1860 fields were established on Plantation Key and

Merritt's Island. And in 1876 planting material from the Keys was set

out all along the central Florida east coast. Shipping to the North

began in 1879. In 1910 there were 5000 to 10,000 acres stretching as

far north as Ft. Pierce. There were more than a dozen families raising

pineapples on Elliott's Key where an average crop was 50,000 to 75,000

dozen fruits, mostly sent by schooner to New York. When the industry

was flourishing, Florida shipped to New York, Philadelphia and

Baltimore one million crates of pineapples a year from the sandy ridge

along the Indian River. It was believed in those days that the

pineapple benefitted by closeness to salt water.

Wood-lath sheds

roofed with palmetto fronds, Spanish moss or tobacco cloth were

constructed to provide shade which promoted vigorous plant growth and

high fruit quality. Wood-burning ovens were scattered through the sheds

for frost protection in winter. Small, open boxcars operating on steam

or horsepower ran on wooden rails the length of the shed to transport

loads of fruit to the packing station. In open fields, plants were

sheltered by palmetto fronds from mid-December to mid-March. 'Smooth

Cayenne' had to be grown in sheds. It was not successful in the open.

One early planter on Eden Island moved his farm to the mainland because

bears ate the ripe fruits. With the coming of the railroad in 1894,

pineapple growing expanded. The 1908-09 crop was 1,110,547 crates. Then

Cuban competition for U.S. markets caused prices to fall and many

Florida growers gave up. The ridge pineapple fields begain to fail as

the humus was exhausted by cultivation. Fertilization was steadily

raising the pH too high for the pineapple. World War I brought on a

shortage of fertilizer, then several freezes in 1917 and 1918

devastated the industry.

In the early 1930's, the United Fruit

Company supplied slips for a new field at White City but the pressure

of coastal development soon reduced this to a small patch. Shortly

after World War II, a plantation of 'Natal Queen' and 'Eleuthera' was

established in North Miami but, after a few years, the operation was

shifted inland to Sebring, in Highlands County, Central Florida, where

it still produces on a small scale.

Varieties

In

international trade, the numerous pineapple cultivars are grouped in

four main classes: 'Smooth Cayenne', 'Red Spanish', 'Queen', and

'Abacaxi', despite much variation in the types within each class.

'Smooth Cayenne'

or 'Cayenne', 'Cayena Lisa' in Spanish (often known in India, Sri

Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand as 'Sarawak' or 'Kew') was selected and

cultivated by Indians in Venezuela long ago and introduced from Cayenne

(French Guyana) in 1820. From there it reached the Royal Botanical

Gardens, Kew, England, where it was improved and distributed to Jamaica

and Queensland, Australia. Because of the plants near freedom from

spines except for the needle at the leaftip and the size-4 to 10 lbs

(1.8 4.5 kg)-cylindrical form, shallow eyes, orange rind, yellow flesh,

low fiber, juiciness and rich mildly acid flavor, it has become of

greatest importance worldwide even though it is subject to disease and

does not ship well. Mainly, it is prized for canning, having sufficient

fiber for firm slices and cubes as well as excellent flavor.

It

was the introduction of this cultivar into the Philippines from Hawaii

in 1912 that upgraded the Philippine industry from the casual growing

of the semi-wild type which was often seedy. There are several clones

of 'Smooth Cayenne' in Hawaii which have been selected for resistance

to mealybug wilt. It is the leading cultivar in Taiwan. In 1975, the

Queensland Department of Primary Industries, after 20 years of breeding

and testing, released a dual purpose cultivar named the 'Queensland

Cayenne'. South Africas Pineapple Research Station, East London, after

20 years of selecting and testing of 'Smooth Cayenne' clones, has

chosen 4 as superior especially for the canning industry.

'Hilo'is

a variant of 'Smooth Cayenne' selected in Hawaii in 1960. The plant is

more compact, the fruit is smaller, more cylindrical; produces no slips

but numerous suckers It may be the same as the 'Cayenne Lisse' strain

grown in Martinique and on the Ivory Coast, the fruit of which weighs

from 2 to 2 3/4 lbs (1-1 1/2 kg) and has a very small crown.

'St. Michael',

another strain of 'Smooth Cayenne' is the famous product of the Azores.

The fruit weighs 5 to 6 lbs (2.25-2.75 kg), has a very small crown, a

small core, is sweet with low acidity, and some regard it as insipid

when fully ripe.

'Giant Kew',

well-known in India, bears a large fruit averaging 6 lbs (2.75 kg),

often up to 10 lbs (4.5 kg) and occasionall up to 22 lbs (10 kg). The

core is large and its extraction results in too large a hole in canned

slices.

'Charlotte Rothschild',

second to 'Giant Kew' in size in India, tapers toward the crown, is

orange-yellow when ripe, aromatic, very juicy. The crop comes in early.

'Baron Rothschild', a Cayenne strain, grown in Guinea, has a smaller

fruit 1 3/4 to 5 lbs (0.8-2 kg) in weight, marketed fresh.

'Perolera'

(also celled 'Tachirense', 'Capachera', 'Motilona', and 'Lebrija') is a

'Smooth Cayenne' type ranking second to 'Red Spanish' in importance in

Venezuela. It has long been grown in Colombia. The plant is entirely

smooth with no spine at the leaftip. The fruit is yellow, large-7 to 9

1bs (3-4 kg) and cylindrical.

'Bumanguesa',

of Venezuela and Colombia, is probably a mutation of 'Perolera'. The

fruit is red or purple externally, cylindrical with square ends,

shallow eyes, deep-yellow flesh, very slender core but has slips around

the crown and too many basal slips to suit modern commercial

requirements.

'Monte Lirio',

of Mexico and Central America, also has smooth leaves with no terminal

spine. The fruit is rounded, white-fleshed, with good aroma and flavor.

Costa Rica exports fresh to Europe.

Other variants of 'Smooth

Cayenne' include the 'Esmeralda' grown in Mexico and formerly in

Florida for fresh, local markets; 'Typhone', of Taiwan; 'Cayenne

Guadeloupe', of Guadeloupe, which is more disease resistant than

'Smooth Cayenne'; and 'Smooth Guatemalan' end 'Palin' grown in

Guatemala; also 'Piamba da Marquita' of Colombia. Some who have made

efforts to classify pineapple strains have proposed grouping all

smooth-leaved types under the collective name 'Maipure'. In Amazonas,

Venezuela, this name is given to a large plant with smooth leaves

stained with red. The fruit has 170 to 190 eyes.

Philipps Platts, a leading pineapple authority, experimented with 60 to

70 cultivars in Florida but 'Red

Spanish'

proved most dependable. Despite the spininess of the plant, it still is

the most popular among growers in the West Indies, Venezuela and

Mexico. 'Red Spanish' constitutes 85% of all commercial planting in

Puerto Rico and 75% of the production for the fresh fruit market. It is

only fair for canning. The fruit is more or less round, orange-red

externally, with deep eyes, and ranges from 3 to 6 lbs (1.36-2.7 kg).

The flesh is pale-yellow, fibrous, with a large core, aromatic and

flavorful. The fruit is hard when mature, breaks off easily and cleanly

at the base in harvesting, and stands handling and transport well. It

is highly resistant to fruit rot though subject to gummosis.

Two

vigorous hybrids of 'Smooth Cayenne' and 'Red Spanish' were developed

at the Agricultural Experiment Station of the University of Puerto Rico

and released in 1970—'P.R. 1-56' and the slightly larger

'P.R. 1

67', both with good resistance to gummosis and mealybug wilt and of

excellent fruit quality. 'P.R. 1 67' averages 5 3/4 lbs (2.5 kg), gives

a high yield—32 tons per acre (79 tons/ha). The fruit is

sweeter

yet with more acidity than 'Red Spanish', less fibrous and good for

marketing fresh and for canned juice. It was introduced into Venezuela

about 1979 and is grown in the State of Lara.

'Cabezona'

('Bull Head', or 'Pina de ague') is a prominent variant (a natural

tetraploid) of 'Red Spanish' long grown in Puerto Rico in the semiarid

region of Lajas, to which it is well suited; also in El Salvador. The

plant is large, over 3 ft (1 m) high; the leaves are gray-green. The

fruit is conical but not as tall as that of 'Valera'; averages 4 to 6

lbs (1.8-2.75 kg) and may reach 18 lbs (8 kg) or more. It is

orange-yellow at maturity, has few fibers and sweet-acid flesh. The

stem is large and extends up into the base of the fruit and if the

fruit is broken off when harvested it leaves a cavity. Consequently, it

must be cut with a machete and later trimmed flush with the base in the

packing house. It is marketed fresh only. It is resistant to gummosis.

Platts reported that it gave a low yield and was disease prone in

Florida. There are small plantings in the States of Trujillo and

Monagas, Venezuela. It has been cultivated frequently in the

Philippines.

'Valera'

('Negrita', or 'Andina'), is an old cultivar originating in Puerto

Rico; it is grown in the States of Lara, Merida and Trujillo in

Venezuela. It is a small to medium plant with long, narrow, spiny,

purple green leaves. The fruit is conical cylindrical, weighing 3 1/2

to 5 1/2 lbs (1.5-2.5 kg); is purple outside with white flesh.

'Valera Amarilla'

is a 'Red Spanish' strain grown in the States of Lara and Trujillo in

Venezuela. The fruit is broad cylindrical and tall with a large crown;

weighs 4 1/2 to 9 lbs (2-4 kg); is yellow externally with very deep

eyes, about 72 to 88 in number. The flesh is pale-yellow and very sweet

in flavor.

'Valera Roja',

grown in Lara, Trujillo and Merida, Venezuela, is a small-to-medium

plant with cylindrical fruit 1 1/2 to 2.2 lbs (0.6-1 kg) in weight,

reddish externally, with 100 eyes. It has pale-yellow flesh.

'Castilla'

is a 'Red Spanish' strain grown in Colombia and El Salvador.

'Cumanesa',

supposedly a selection of 'Red Spanish', grown mainly in the State of

Sucre, Venezuela, is a medium-sized plant, very spiny, producing an

oblong fruit with a large crown. It is orange-yellow externally; weighs

2 to 3 3/4 lbs (0.9-1.70 kg). and has yellowish-white flesh.

'Morada',

believed to be a variant of 'Red Spanish', is one of the less important

cultivars of Colombia and the State of Monagas, Venezuela. The plant is

large, with long, narrow, purple-red leaves. The fruit is

broad-cylindrical, purple-red externally, with white flesh.

'Monte Oscuro'

('Pilon'), is a large plant with broad, sawtoothed, spiny-edged leaves.

The fruit is barrel-shaped, large, weighing 6.6 lbs (3 kg); has 160-180

medium-deep eyes; is yellow outside with deep-yellow, fibrous flesh. It

is ,grown among Mauritia palms in the State of Monagas, Venezuela.

'Abacaxi'

(also called 'White Abacaxi of Pernambuco', 'Pernambuco', 'Eleuthera',

and 'English') is well known in Brazil, the Bahamas and Florida. The

plant is spiny and disease-resistant. Leaves are bluish-green with

red-purple tinge in the bud. The numerous suckers need thinning out.

The fruit weighs 2.2 to ll lbs (1-5 kg), is tall and straight-sided;

sunburns even when erect. It is very fragrant. The flesh is white or

very pale yellowish, of rich, sweet flavor, succulent and juicy with

only a narrow vestige of a core. This is rated by many as the most

delicious pineapple. It is too tender for commercial handling, and the

yield is low. The fruit can be harvested without a knife; breaks off

easily for marketing fresh.

'Sugarloaf'

(also called 'Pan de Azucar') is closely related to 'Abacaxi', and much

appreciated in Central and South America, Puerto Rico, Cuba and the

Philippines. The leaves of the plants and crowns pull out easily and

this fact gave rise to the unreliable theory that pineapple ripeness is

indicated by the looseness of the leaves. The fruit is more or less

conical, sometimes round; not colorful; weighs 1 1/2 to 3 lbs

(0.68-1.36 kg). Flesh is white to yellow, very sweet, juicy. This

cultivar is too tender for shipping.

Among several strains of

'Sugarloaf' are 'Papelon', and 'Black Jamaica', and probably also

'Montufar' ('Sugar Slice' of Guatemala). The latter fruit is green,

conical, weighs 2 to 5 1/2 lbs (0.8 2.5 kg); has yellow, very juicy,

flesh, sweet yet a little acid. This pineapple also is too tender to

ship.There are a number of tropical American cultivars not categorized

as to groups, and among them are:

'Brecheche',

grown to a limited extent in southern Venezuela, is a small fruit with

small, spineless crown. Average weight is 1 1/2 to 2.2 lbs (0.7-1 kg).

The fruit is yellow externally. Flesh is yellow, with little fiber,

small core, very fragrant, very juicy.

'Caicara',

grown to a small extent in the State of Bolivar, Venezuela, is a large

fruit weighing 4 to 5 1/2 lbs (1.8-2.5 kg). with a large, spiny crown.

It is cylindrical conical with deep eyes; yellow externally with white

flesh, a little fiber, very juicy, with large core.

'Chocona'

and 'Sante Clara' are cultivars that have been introduced into Trinidad.

'Congo Red'

is a plant with bright-red, long-lasting flowers. The fruit bends over

and cracks in hot, dry weather. It weighs up to 5 lbs (2.25 kg), is

waxy, with yellow flesh of good flavor.

'Panare',

named after the tribe of Indians that has grown it for a long time, is

commercially grown to a small extent in the State of Bolivar,

Venezuela. The plant is of medium size with long, spiny leaves. The

fruit is bottle-shaped, small, 1 to 1 l/2 lbs (0.45-0.70 kg), with

small crown; ovate, with deep eyes; orange externally with deep-yellow

flesh; slightly fragrant, with little fiber and small core.

'Santa Marta'

of Colombia, is subject to cracking of the core in hot, dry weather.

In

Peru, farmers still grow the old common 'Criolla' because it can be

sold fresh and is not easily damaged in shipment. But modern pineapple

production in that country depends on the 'Smooth Cayenne' for canning.

Minor

cultivars in Colombia include: 'Amarilla de Cambao', 'Amarilla de

Tocaima', 'Blanca Chocoana', 'Blanca del Atrato', 'Blanca de Valle del

Cauca', 'Cimarrona', 'Espanola de Santander', 'Hartona', 'Jamaiquena'

and 'Manzana'.

'Cacho de Venado'

is grown to a small extent in Monagas and Sucre, and 'Injerta' in

Trujillo, Venezuela.

'Pearl',

'Itaparica', 'Paulista', and 'Maranhao' (or 'Amarella') are spoken of

in Brazil; 'Azucaron' in El Salvador; 'Roja' in Mexico. It remains to

be determined if some of these names are merely synonyms for cultivars

already referred to.

'Mauritius'

(also known as 'European Pine', 'Malacca Queen', 'Red Ceylon' and 'Red

Malacca') is one of the 2 leading pineapple cultivars in Malaya; also

important in India and Ceylon. The leaves are dark green with broad red

central stripe and red spines on the margins. The fruit is small, 3 to

5 lbs (1.36-2.25 kg), yellow externally; has a thin core and very sweet

flesh. It is sold fresh and utilized for juice.

'Singapore Red'

(Also called 'Red Jamaica', 'Singapore Spanish', 'Singapore Queen',

'Singapore Common') is second to 'Mauritius' in popularity. The leaves

are usually all-green but sometimes have a reddish stripe near the

margins; they are rarely spiny except at the tips. The fruits,

cylindrical, reddish, with deep eyes, are small—3 1/2 to 5

lbs

(1.6-2.25 kg)—with slender core, fibrous, golden-yellow

flesh;

insipid raw but valued for canning. The plant is disease and

pest-resistant.

The related 'Green Selangor' (also called 'Selangor

Green', 'Green Spanish', and 'Selassie') of Malaysia has all-green

leaves prickly only at the tips. The flesh is golden-yellow, often with

white dots. This cultivar is grown for canning.

'Queen'

(also called 'Common Rough' in Australia) is the leading cultivar in

South Africa, Queensland and the Philippines. The plant is dwarf,

compact, more cold-resistant and more disease-resistant then 'Smooth

Cayenne'. It matures its fruit early but suckers freely and needs

thinning, and the yield is low. The fruit is conical, deep-yellow, with

deep eyes; weighs 1 to 2 1/2 lbs (0.45-1.13 kg); is less fibrous than

'Smooth Cayenne', but more fragrant; it is juicy, of fine flavor with a

small, tender core. It is sold fresh and keeps well. It is only fair

for canning because of its shape which makes for much waste.

'Natal Queen'

of South Africa, also grown in El Salvador, produces many suckers. The

fruit weighs 1 1/2 to 2 lbs (0.75-0.9 kg).

'MacGregor',

a variant of 'Nasal Queen' selected in South Africa and grown also in

Queensland, is a spreading, more vigorous plant with broad leaves and

large suckers produced less freely. The fruit is cylindrical, medium to

large, with firm flesh and flavor resembling 'Queen'.

'James Queen'

(formerly 'Z') is a mutation of 'Nasal Queen' that originated in South

Africa. It has larger fruit with square shoulders.

'Ripley'

or 'Ripley Queen', ,grown in Queensland, is a dwarf, compact plant with

crimson tinge on leaves; takes 22 weeks from flowering to fruit

maturity; is an irregular bearer. The fruit weighs 3 to 6 lbs (1.36-2.7

kg); is pale-copper externally; flesh is pale-yellow, non-fibrous, very

sweet and rich. In Florida this cultivar tends to produce suckers

without fruiting.

'Alexandria', a selection of 'Ripley Queen' in

Queensland, is more vigorous with large suckers and fruit. The fruit is

conical, tender, with 'Ripley Queen' flavor.

'Egyptian Queen'

was introduced into Florida in 1870. It was popular at first, later

abandoned. The fruit weighs 2 to 4 lbs (0 9-1.8 kg).

'Kallara Local'

is a little-known cultivar in India. Minor strains in Thailand are

'Pattavia', 'Calcutta', 'Sri Racha', 'Intorachit' and 'Chantabun'.

In

the evaluation of pineapples, the crown can be an asset or a liability.

Small crowns detract from the decorative appearance of the fruit; large

crowns are more attractive but hamper packing and constitute too great

a proportion of inedible material from the standpoint of the purchaser.

Climate

The

pineapple is a tropical or near tropical plant limited (except in

greenhouses) to low elevations between 30°N and 25°S. A

temperature range of 65°-95°F (18.33-45°C) is

most

favorable, though the plant can tolerate cool nights for short periods.

Prolonged cold retards growth, delays maturity and causes the fruit to

be more acid. Altitude has an important effect on the flavor of the

fruit. In Hawaii, the 'Smooth Cayenne' is cultivated from sea level up

to 2,000 ft (600 m). At higher elevations the fruit is too acid. In

Kenya, pineapples grown at 4500 ft (1371 m) are too sweet for canning;

between 4500 and 5700 ft (1371-1738 m) the flavor is most suitable for

canning; above 5700 ft (1738 m) the flavor is undesirably acid.

Pineapples are grown from sea level to 7545 ft (2300 m) in Ecuador but

those in the highlands are not as sweet as those of Guayaquil.

Ideally,

rainfall would be about 45 in (1,143 mm), half in the spring and half

in the fall; though the pineapple is drought tolerant and will produce

fruit under yearly precipitation rates ranging from 25 to 150 in

(650-3,800 mm), depending on cultivar and location and degree of

atmospheric humidity. The latter should range between 70 and 80 degrees.

Soil

The

best soil for pineapple culture is a well-drained, sandy loam with a

high content of organic matter and it should be friable for a depth of

at least 2 ft (60 cm), and pH should be within a range of 4.5 to 6.5.

Soils that are not sufficiently acid are treated with sulfur to achieve

the desired level. If excess manganese prevents response to sulfur or

iron, as in Hawaii, the plants require regular spraying with very weak

sulfate or iron. The plant cannot stand waterlogging and if there is an

impervious subsoil, drainage must be improved. Pure sand, red loam,

clay loam and gravelly soils usually need organic enrichment. Filter

presscake from sugar mills, worked into clay soils in Puerto Rico,

greatly enhances plant vigor, fruit yield, number of slips and suckers.

Propagation

Crowns

(or "tops"), slips (called nlbs or robbers in New South Wales), suckers

and ratoons have all been commonly utilized for vegetative

multiplication of the pineapple. To a lesser degree, some growers have

used "stumps", that is, mother plant suckers that have already fruited.

Seeds are desired only in breeding programs and are usually the result

of hand pollination. The seeds are hard and slow to germinate.

Treatment with sulfuric acid achieves germination in 10 days, but

higher rates of germination (75-90 % ) and more vigorous growth of

seedlings results from planting untreated seeds under intermittent mist.

The

seedlings are planted when 15-18 months old and will bear fruit 16-30

months later. Vegetatively propagated plants fruit in 15-22 months.

In

Queensland, tops and slips from the summer crop of 'Smooth Cayenne' are

stored upside down, close together, in semi-shade, for planting in the

fall. Some producers salvage the crowns from the largest grades of

fruits going through the processing factory to be assured of high

quality planting material.

South African experiments with

'Smooth Cayenne' have shown medium-size slips to be the best planting

material. Next in order of yield were large crowns, medium-size

suckers, medium-size crowns and large suckers. Medium and large

suckers, however, fruited earlier. Trimming of basal leaves increased

yields. Workers in Johore, Malaya, report, without specifying cultivar,

that large crowns give highest yield and more slips, followed by small

crowns, big slips, small slips, large and small suckers in descending

order.

With the 'Red Spanish' in Puerto Rico, the utilization of

large slips for planting in the first quarter of the year, medium slips

during the next six months, and small slips in the final quarter,

provides fruits of the maximum size over an extended period of harvest.

Storage of slips until optimum planting time prevents premature bloom

and diminished fruit size.

The 'Red Spanish' reaches shipping-green stage (one week before

coloring begins) in Puerto Rico 150 days after natural blooming.

In

South Africa the 'Queen' is grown mainly from stumps, secondly from

suckers. The stumps which have fruited are detached from the mother

plant as soon as possible to avoid their developing suckers of their

own. In comparison with suckers, the stumps are consistently heavier in

yield after the 4th crop. When suckers are used, those of medium size,

approximately 18 in (45 cm) long, planted shallow and upright, yield

best.

In the past, growers preferred plants that supplied

abundant basal slips for planting, not recognizing the fact that such

plants gave smaller fruits than those without slips or suckers. Also,

breeders aim toward elimination of slips to facilitate harvesting.

Because of the increased demand for planting material, a new method of

mass propagation received wide attention in 1960. During the harvest,

plants that have borne single-crowned, superior fruits without basal

slips are selected and marked. Following harvest, these plants are cut

close to the ground, the leaves are stripped off and the

stems—usually 1 to 2 ft (30-60 cm) long and 3 to 4 in (7.5-10

cm)

thick—are sliced lengthwise into 4 triangular strips. The

strips

are disinfected and placed 4 in (10 cm) apart, with exterior side

upward, in beds of sterilized soil, semi-shaded and

sprinkler-irrigated. Shoots emerge in 3 to 5 weeks and are large enough

to transplant to the nursery in 6 to 8 weeks. 'Smooth Cayenne' yields

an average of 3 shoots per slice. 'Red Spanish' and 'Natal Queen', 4

per slice.

This use of the stem is a major improvement over the

former practice of allowing it to develop suckers high up after the

fruit is harvested. If such suckers bear fruit in situ they are not

strong enough to support it and collapse. They are better removed for

planting, but repeated removal of suckers weakens the mother plant.

In

Sri Lanka, the shortage of planting material inspired experiments at

first utilizing stem cross-sections 1 in (2.5 cm) thick—15 to

24

from each stem. These sprouted in 4 weeks but plant growth was slow and

fruiting was delayed for 30 months. Most of the cuttings developed a

single sprout, some as many as 5, others, none at all. Accordingly,

this technique was abandoned in favor of a system developed for

purposes of reproducing a selected strain in Hawaii. Stems are cut into

segments bearing 3 to 5 whorls of leaves. The leaves are trimmed to 4

to 5 in (10-12.5 cm) and the disinfected cuttings set upright in beds

until each gives rise to one strong plantlet which is then transferred

to the nursery.

The butts, or bases, of mother plants, with

leaves intact, are laid end to end in furrows in nurseries and covered

with 2 to 3 in (5-7.5 cm) of soil. Sprouting occurs in 6 to 8 weeks.

The butts give an average of 6 suckers each, though some have put forth

up to 25. A one-acre (0.4 ha) nursery of 25,000 butts, therefore,

yields between 100,000 and 200,000 suckers.

The Pineapple Research

Institute in Hawaii has also employed axillary buds at the base of

crowns. Each crown segment may develop 20 plantlets. This method has

been adopted in Sri Lanka for perpetuating superior strains but not for

commercial cultivation because the resulting plants require 24 months

or more to fruit.

In India, because of low production of slips

and suckers in 'Smooth Cayenne', crown cuttings (15-16 per crown) have

been adopted for propagation with 95% success, and this method is

considered more economical than the utilization of butts.

Vegetative

propagation does not assure facsimile reproduction of pineapple

cultivars, as many mutations and distinct clones have occurred in spite

of it.

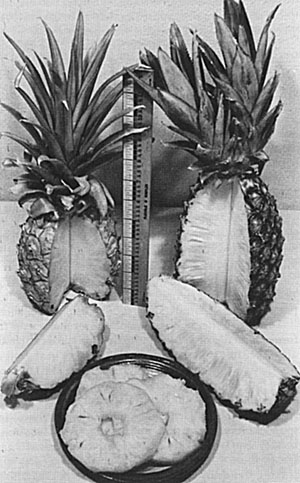

Fig.

7: 'Red Spanish' (left) and 'Abacaxi' (called 'English' in the Bahamas)

(right). In: K. and J. Morton, Fifty Tropical Fruits of Nassau, 1946.

Culture

The

land should be well prepared at the outset because the pineapple is

shallow-rooted and easily damaged by post-planting cultivation.

Fumigation of the soil contributes to high quality and high yields.

Planting:

In small plots or on very steep slopes, planting is done manually using

the traditional short-handled narrow-bladed hoe, the handle of which,

12 in (30 cm) long, is used to measure the distance between plants.

Crowns are set firmly at a depth of 2 in (5 cm); slips and suckers at 3

1/2 to 4 in (9 10 cm). Butts, after trimming and drying for several

days, are laid end-to-end in furrows and covered with 4 in (10 cm) of

soil.

Double-rowing has been standard practice for many years,

the plantlets set 10 to 12 in (25 30 cm) apart and staggered, not

opposite, in the common rows, and with 2 ft (60 cm) between the two

rows. An alley 3, 5 1/2 or 6 ft (.9, 1.6 or 1.8 m) wide is maintained

between the pairs, allowing for plant populations of 17,400, 15,800 or

14,500 per acre (42,700, 37,920 or 33,800 per ha) respectively. Close

spacing gives highest total crop weight—e.g.. 18,000

plants/acre

= 28.8 tons (43,200 plants/ha = 69.12 tons). However, various trials

have shown that overcrowding has a negative effect, reducing fruit size

and elongating the form undesirably, and it reduces the number of slips

and suckers per plant. Density trials with 'P.R. 1-67' in Puerto Rico

demonstrated that 21,360 plants per acre (51,265/ha) yielded 35.8

tons/:acre (86 tons/ha) in the main crop and 18.9 tons/acre (45.43

tons/ha) in the ratoon crop, but only one slip per plant for

replanting. Excessively wide spacing tends to induce multiple crowns in

'Smooth Cayenne' in Hawaii and in 'Red Spanish' in Puerto Rico.

Some

plantings are mulched with bagasse. In large operations,

asphalt-treated paper, or black plastic mulch is regarded as essential.

It retards weeds, retains warmth in cool seasons, reduces loss of soil

moisture, and can be laid by machines during the sterilization and

pre-fertilization procedures. Mulch necessitates removal of basal

leaves of crowns, slips and suckers and the use of a tool to punch a

hole at the pre-marked planting site for the insertion of each

plantlet. The mulch is usually rolled onto rounded beds 3 1/4 ft (1 m)

wide.

Mechanical

planting:

Research on the potential of machines to replace the hard labor of

planting pineapples was begun in Hawaii in 1945. A homemade device was

first employed in Queensland in 1953. Early semi-mechanical planters

were self propelled platforms with driver and two men who made the

holes in the mulch and set the plants in place. With a 2-row planter, 3

men can set 7,000 plants per hour of operation. Frequent stops are

necessary to reload with planting material. With improved equipment,

mechanical planting has become standard practice in large plantations

everywhere. The most sophisticated machines have attachments which

concurrently apply premixed fertilizer and lay a broad center strip of

mulch, set the plantlets along each edge, and place a narrow strip

along the outer sides. The only manual operation, apart from driving,

is feeding of the plantlets to the planting unit. With this system, up

to 50,000 plants have been set out per day.

Fertilization:

Nitrogen is essential to the increase of fruit size and total yield.

Fertilizer trials in Kenya show that a total of 420 lbs N/acre (471.7

kg/ha) in 4 equal applications during the first year is beneficial,

whereas no advantage is apparent from added potassium and, phosphorus.

Puerto Rican studies have indicated that maximum yields are achieved by

urea sprays supplying 147 lbs N/acre (151 kg/ha). In Queensland, total

yield of mother plants and ratoons was increased 8% by urea spraying.

Normal rate of application is 3 1/2 gals (13.3 liters) per 1,000

plants. On acid Bayamon sandy clay in Puerto Rico, addition of

magnesium to the fertilizer mix or applying it as a spray (300 lbs

magnesium sulfate per acre—327 kg/ha) increased yield by 3

tons/acre (7 tons/ ha). On sloping, stony clay loam high in potassium,

Queensland growers obtained high yields of 'Smooth Cayenne' from side

dressings of NPK mixture 5 times a year. On poor soils, nitrogen and

potassium levels of the plants may become low toward the end of the

crop season. This must be anticipated early and suitable adjustments

made in the application of nutrients. Potassium uptake is minimal after

soil temperatures drop below 68°F (20°C). On fine sandy

loam in

Puerto Rico, the cultivar 'P.R. 1-67' performed best with 13-3-12

fertilizer applied at the rate of 1.5 tons/acre (3.74 tons/ha). In this

expertmeet, 13,403 plants/acre (32,167/ha) produced 9,882 fruits/acre

(23,717/ha), weighing 31.28 tons/acre (75 tons/ha). In Venezuela, 6,250

medium-size fruits per acre (15,000 fruits/ha) is considered a very

good crop.

Fruit weight has been considerably increased by the

addition of magnesium. In Puerto Rican trials, magnesium treatment

resulted in 54% more total weight providing an average of 2.7 more

tons/acre (64.8 tons/ha) than in control plots. Fruit size and total

yield have been enhanced by applying chelated iron with nitrogen; also,

where chlorosis is conspicuous, by accompanying nitrogen with foliar

sprays of 0.10% iron and manganese.

Some growers thin out suckers and slips to promote stronger growth of

those that remain.

Irrigation:

Irrigation is desirable only in dry seasons and should not exceed 1 in

(2.5 cm) semi-monthly.

Weed Control:

Manual weeding in pineapple fields is difficult and expensive. It

requires protective clothing and tends to induce soil erosion. Coir

dust has been used as mulch in Sri Lanka to discourage weeds but it has

a deleterious effect on the crop, delaying or preventing flowering. The

use of paper or plastic mulch and timely application of approved

herbicides are the best means of preventing weed competition with the

pineapple crop.

Flower

Induction:

Pineapple flowering may be delayed or uneven, and it is highly

desirable to attain uniform maturity and also to control the time of

harvest in order to avoid overproduction in the peak periods. In 1874

in the Azores it was accidentally discovered that smoke would bring

pineapple plants into bloom in 6 weeks. The realization that ethylene

was the active ingredient in the smoke led to the development of other

methods.

As far back as 1936, compressed acetylene gas, or a

spray of calcium carbide solution (which generates acetylene) were

employed to expedite uniform blooming. Some growers have merely

deposited calcium carbide in the crown of each plant to be dissolved by

rain. A more advanced method is the use of the hormone,

a-naphthaleneacetic acid (ANA) or B naphylacetic acid (BNA) which

induce formation of ethylene. In recent years, B-hydroxyethyl hydrazine

(BOH) came into use. Treatment is given when the plants are 6 months

old, 3 months before natural flowering time. The plants should have

reached the 30 leaf stage at this age.

Spraying of a water

solution of ANA on the developing fruit has increased fruit size in

'Smooth Cayenne' in Hawaii and Queensland. In West Malaysia, spraying

'Singapore Spanish' 6 weeks after flowering with Planofix, an ANA-based

trade product, delayed fruit maturity, increased fruit size, weight and

acidity. Similar results have been seen after hormone treatment of

'Cayenne Lisse' on the Ivory Coast.

Trials with 'Sugarloaf' in

Ghana showed calcium carbide and BOH equally effective on 42-to

46-week-old plants, and Ethrel performed best on 35-to 38-week-old

plants. 'Sugarloaf' seems to respond 10 days earlier than 'Red Spanish'.

Ethrel,

or the more recently developed Ethephon, applied at the first sign of

fruit ripening in a field will cause all the fruit to ripen

simultaneously. It brings the ratoons into fruit quickly. There is a

great saving in harvesting costs because it reduces the need for

successive pickings.

Plants treated with naphthaleneacetic acid

produce long, cylindrical, pointed fruits, maturing over an extended

period of time, ripening first at the base while the apex is still

unripe. Ethylene treatment results in a square shouldered, shorter

fruit maturing over a shorter period and ripening more uniformly.

In Puerto Rico, treatment in 'Cabezona' can be done to induce flowering

at any time of the year.

Pests

Nematodes (Rotylenchulus,

Meloidogyne, Pratylenchus, Ditylenchus, Helicotylenchus,

and other genera) cause stunting and degeneration in pineapple plants

unless soil is fumigated. In Queensland, nematicides have increased

yields by 22-40%. Crop rotation has been found effective in Puerto

Rico. Turning the field over to Pangola grass (Digitaria decumbens

Stent.) or green foxtail grass (Setaria

viridis

Beauv.) for 3 years suppresses nematode populations and benefits the

soil but may not be practicable unless spare land is available for

pineapple culture in the interim.

Mealybugs (Pseudococcus

brevipes and P.

neobrevipes)

attack leaf bases and cause wilt. The leaves turn orange-brown and

wither due to root rot. Prevention requires spraying and dusting to

control the fire ants (Solenopsis

spp. ) which carry the mealybugs from diseased to healthy plants.

Control is difficult because there are many weeds and other local

plants acting.as mealybug hosts. Some success was achieved in Florida

in combatting mealybugs with the parasitic wasp, Hambletonia pseudococciaa

Comp., though the general use of insecticides limits the activity of

the wasp.

The pineapple mite, or so-called red spider (Dolichote-tranychus

(or Stigmacus)

floridanus

(Banks) also attacks leaf bases and is troublesome during prolonged

droughts, heavily infesting the slips. The pineapple red scale (Diaspis bromeliae)

has been a minor pest in Florida. Since 1942 this scale has spread to

many pineapple districts in southeastern Queensland, with occasional

serious infestations. Natural predators afford about 40% control. The

palmetto beetle (Rhynchophorus

cruentatus), which feeds on palm logs, enters the bud and

lays eggs in young fruits and the fruit stalk.

The sap beetle (Carpophilus

humeralis)

is one of the main enemies of pineapple fruits in Puerto Rico, Hawaii

and Malaysia and is especially attracted to fruits affected by

gummosis. Populations have been diminished by sanitary procedures and

growing of cultivars resistant to gummosis, and chemical control is

being evaluated.

In Brazil, larvae of the large moth, Castnia licus, and

of the butterfly, Thecla

basilides, damage the fruit. The latter is a problem in

other parts of tropical America also and in Trinidad.

Cutworms

eat holes in the base of the immature fruit. Fruit fly larvae do not

pupate in 'Smooth Cayenne' but new hybrids lack resistance and may

require treatment.

In New South Wales, poison baits are employed

to combat fruit damage by crows, rats and mice. Rats may eat the base

of the stem and destroy ratoons and suckers. Rabbits in winter eat the

leaves as high as they can reach.

Diseases

In Queensland, top rot and root rot are caused by the soil fungi Phytophthora cinnamomi

and P. nicotianae

var. parasitica

which are most prevalent in prolonged wet weather in autumn and winter.

Improved drainage helps reduce the risk and monthly spraying with

fungicide gives good control. P. cinnamomi may also cause rot in green

fruit on ratoons. These diseases are largely prevented by the use of

paper or plastic mulch on raised beds.

Base rot is caused by the fungus Ceratocystis

paradoxa, especially where drainage is poor. The imperfect

form (conidial state) of this fungus, known as Thielaviopsis paradoxa,

causes butt rot in planting material, also soft rot or breakdown of

fruits during shipment and storage. If 1/4-ripe 'Red Spanish' fruits

are kept at temperatures between 44.6° and 46.4°F

(7°-8°C) while in transit, soft rot will not develop.

Fusarium

spp. in the soil are the source of wilt. Black heart is a physiological

disorder not visible externally, usually occuring in winter

particularly in locations where air flow is inadequate. Highest

incidence in West Africa has been reported in midsummer. It begins as

"endogenous brown spot" at the base of the fruitless close to the core.

Later, affected areas merge. It has been attributed to chilling or low

light intensity from dense planting or cloudiness. It can be controlled

by one-day heat treatment at 90° to 100°F

(32°-38°C)

before or after refrigerated storage. In 1974, the microorganism Erwinia chrysanthemi

was identified in Malaya as the cause of bacterial heart rot and fruit

collapse.

Yellow spot virus on leaves is transmitted by Thrips tabaci Lind. Black

speck and water blister are mentioned among other problems of the

pineapple.

A

condition called Crookneck is caused by zinc deficiency. It occurs

mainly in plants 12-15 months old but is also frequent in suckers. The

heart leaves become curled and twisted, waxy, brittle, and light

yellowish-green. Sometimes the plant bends over and grows in a nearly

horizontal position. Small yellow spots appear near the edges of the

leaves and eventually merge and form blisters. Later, these areas

become grayish or brownish and sunken. Treatment is usually a 1%

solution of zinc sulfate. Many growers use a combined spray of 10%

urea. 2% iron sulfate and 1% zinc sulfate. If burning occurs. the

proportion of urea should be changed to 5%. Excessive use of urea for

this or any other purpose can lead to leaf tip dieback and yellowing of

older leaves due to the biuret content in urea.

Copper deficiency is evident in concave leaves with dead tips and

waxiness without bloom on the underside.

Sunburn

or sunscald develops when fruits fall over and expose one side to the

sun, though 'Abacaxi' may sunburn even when erect. Affected fruits soon

rot and become infested with pests. They must be cut as soon as noticed

and safely disposed of where they will not contaminate other fruits.

Dry grass, straw, excelsior or brown paper sleeves may be placed over

fruits maturing in the summer to prevent sunburn.

Harvesting

It

is difficult to judge when the pineapple is ready to be harvested. The

grower must depend a great deal on experience. Size and color change

alone are not fully reliable indicators. Conversion of starch into

sugars takes place rapidly in just a few days before full maturity. In

general, for the fresh fruit market, the summer crop is harvested when

the eye shows a light pale green color. At this season, sugar content

and volatile flavors develop early and steadily over several weeks. The

winter crop is about 30 days slower to mature, and the fruits are

picked when there is a slight yellowing around the base. Even then,

winter fruit tends to be more acid and have a lower sugar level than

summer fruit, and the harvest period is short. Fruits for canning are

allowed to attain a more advanced stage. But overripe fruits are

deficient in flavor and highly perishable.

Maturity studies

conducted with 'Giant Kew' in India showed that highest quality is

attained when the fruit is harvested at a specific gravity of

0.98-1.02, total soluble solids of 13.8-17%, or total soluble

solids/acid ratio of 20.83-27.24 with development of external yellow

color. Some people judge ripeness and quality by snapping a finger

against the side of the fruit. A good, ripe fruit has a dull, solid

sound; immaturity and poor quality are indicated by a hollow thud.

In

manual harvesting, one man cuts off or breaks off the fruits (depending

on the cultivar) and tosses them to a truck or passes them to 2 other

workers with baskets who convey them to boxes in which they are

arranged with the stems upward for the removal of bracts and

application of a 3% solution of benzoic acid on the cut stem of all

fruits not intended for immediate processing. The harvested fruits must

be protected from rain and dew. If moist, they must be dried before

packing. All defective fruits are sorted out for use in processing.

If

the work is semi-mechanized, the harvesters decrown and trim the fruits

and place them on a 30-ft conveyor boom which extends across the rows

and carries the fruits to a bin on a forklift which loads it onto a

truck or trailer. Some conveyors take the fruits directly into the

canning factory from the field. In most regions of the world,

pineapples are commonly marketed with crowns intact, but there is a

growing practice of removing the crowns for planting. For the fresh

fruit market, a short section of stem is customarily left on to protect

the base of the fruit from bruising during shipment.

Total

mechanical harvesting is achieved by 2 hydraulically operated conveyors

with fingers on the top conveyor to snap off the fruit, the lower

conveyor carrying it away to the decrowners. After the fruit has been

conveyed away, the workers go through the field to collect the crowns

(where they have been left on the tops of the plants) and place them on

the conveyors for a trip to the bins which are then fork lifted and the

crowns dumped into a planting machine.

Life of plantation

In

Florida, 'Abakka' fields were maintained for 2, 3, or 4 crops. Some

plantings of 'Red Spanish' were prolonged for 25-26 years. In current

practice, after the harvesting of the first crop, workers trim off all

but 2 ratoons which will bear fruit in 15-18 months. Perhaps there may

be a second or third ratoon crop. Then the field is cleared to minimize

carryover of pests and diseases. The method will vary with the interest

in or practicality of making use of by products. In Malaya, fields have

been cleared by cutting the plants, leaving them to dry for 12-16

weeks, then piling and burning. Spraying with kerosene or diesel fuel

makes burning possible in 9 weeks. Spraying with Paraquat allows

burning in 3 weeks but does not destroy the stumps which take 3-5

months to completely decay while new plants are set out between them.

Field

practices will differ if pineapples are interplanted with other crops.

In Malaya, pineapples have been extensively grown in young rubber

plantations. In India and Sri Lanka the pineapple is often a catchcrop

among coconuts. Venezuelan farmers may interplant with citrus trees or

avocados.

Storage

Cold

storage at a temperature of 40°F (4.44°C) and lower

causes

chilling injury and breakdown in pineapples. At 44.6-46.4°F

(7-8°C) and above, 80-90% relative humidity and adequate air

circulation, normal ripening progresses during and after storage. At

best, pineapples may be stored for no more than 4-6 weeks. There is a

possibility that storage life might be prolonged by dipping the fruits

in a wax emulsion containing a suitable fungicide. Irradiation extends

the shelf life of half- ripe pineapples by about one week.

Food Uses

In

Puerto Rico and elsewhere in the Caribbean, Spaniards found the people

soaking pineapple slices in salted water before eating, a practice

seldom heard of today.

Field ripe fruits are best for eating

fresh, and it is only necessary to remove the crown, rind, eyes and

core. In Panama, very small pineapples are cut from the plant with a

few inches of stem to serve as a handle, the rind is removed except at

the base, and the flesh is eaten out-of-hand like corn on the cob. The

flesh of larger fruits is cut up in various ways and eaten fresh, as

dessert, in salads, compotes and otherwise, or cooked in pies, cakes,

puddings, or as a garnish on ham, or made into sauces or preserves.

Malayans utilize the pineapple in curries and various meat dishes. In

the Philippines, the fermented pulp is made into a popular sweetmeat

called nata de pina. The pineapple does not lend itself well to

freezing, as it tends to develop off flavors.

Canned pineapple

is consumed throughout the world. The highest grade is the skinned,

cored fruit sliced crosswise and packed in sirup. Undersize or overripe

fruits are cut into "spears", chunks or cubes. Surplus pineapple juice

used to be discarded after extraction of bromelain (q.v.). Today there

is a growing demand for it as a beverage. Crushed pineapple, juice,

nectar, concentrate, marmalade and other preserves are commercially

prepared from the flesh remaining attached to the skin after the

cutting and trimming of the central cylinder. All residual parts cores,

skin and fruit ends are crushed and given a first pressing for juice to

be canned as such or prepared as sirup used to fill the cans of fruit,

or is utilized in confectionery and beverages, or converted into

powdered pineapple extract which has various roles in the food

industry. Chlorophyll from the skin and ends imparts a greenish hue

that must be eliminated and the juice must be used within 20 hours as

it deteriorates quickly. A second pressing yields "skin juice" which

can be made into vinegar or mixed with molasses for fermentation and

distillation of alcohol.

In Africa, young, tender shoots are

eaten in salads. The terminal bud or "cabbage" and the inflorescences

are eaten raw or cooked. Young shoots, called "hijos de pina" are sold

on vegetable markets in Guatemala.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

| Moisture |

81.3-91.2 g |

| Ether Extract |

0.03 0.29 g |

| Crude Fiber |

0.3-0.6 g |

| Nitrogen |

0.038-0.098 g |

| Ash |

0.21-0.49 g |

| Calcium |

6.2 37.2 mg |

| Phosphorus |

6.6-11.9 mg |

| Iron |

0.27-1.05 mg |

| Carotene |

0.003 0.055 mg |

| Thiamine |

0.048 0.138 mg |

| Riboflavin |

0.011-0.04 mg |

| Niacin |

0.13-0.267 mg |

| Ascorbic Acid |

27.0-165.2 mg |

*Analyses of ripe pineapple made in Central America. |

|

Sugar/acid

ratio and ascorbic acid content vary considerably with the cultivar.

The sugar content may change from 4% to 15% during the final 2 weeks

before full ripening.

Toxicity

When unripe, the pineapple is not only inedible but poisonous,

irritating the throat and acting as a drastic purgative.

Excessive consumption of pineapple cores has caused the formation of

fiber balls (bezoars) in the digestive tract.

Other Uses

Bromelain:

The proteolytic enzyme, bromelain, or bromelin, was formerly derived

from pineapple juice; now it is gained from the mature plant stems

salvaged when fields are being cleared. The yield from 368 lbs (167 kg)

of stern juice is 8 lbs (3.6 kg) of bromelain. The enzyme is used like

papain from papaya for tenderizing meat and chill proofing beer; is

added to gelatin to increase its solubility for drinking; has been used

for stabilizing latex paints and in the leather-tanning process. In

modern therapy, it is employed as a digestive and for its

anti-inflammatory action after surgery, and to reduce swellings in

cases of physical injuries; also in the treatment of various other

complaints.

Fiber:

Pineapple leaves yield a strong, white, silky fiber which was extracted

by Filipinos before 1591. Certain cultivars are grown especially for

fiber production and their young fruits are removed to give the plant

maximum vitality. The 'Perolera' is an ideal cultivar for fiber

extraction because its leaves are long, wide and rigid. Chinese people

in Kwantgung Province and on the island of Hainan weave the fiber into

coarse textiles resembling grass cloth. It was long ago used for thread

in Malacca and Borneo. In India the thread is prized by shoemakers and

it was formerly used in the Celebes. In West Africa it has been used

for stringing jewels and also made into capes and caps worn by tribal

chiefs. The people of Guam hand-twist the fiber for making fine casting

nets. They also employ the fiber for wrapping or sewing cigars. Pina

cloth made on the island of Panay in the Philippines and in Taiwan is

highly esteemed. In Taiwan they also make a coarse cloth for farmers'

underwear.

The outer, long leaves are preferred. In the manual

process, they are first decorticated by beating and rasping and

stripping, and then left to ret in water to which chemicals may be

added to accelerate the activity of the microorganisms which digest the

unwanted tissue and separate the fibers. Retting time has been reduced

from 5 days to 26 hours. The rested material is washed clean, dried in

the sun and combed. In mechanical processing, the same machine can be

used that extracts the fiber from sisal. Estimating 10 leaves to the lb

(22 per kg), 22,000 leaves would constitute one ton and would yield

50-60 lbs (22-27 kg) of fiber.

Juice:

Pineapple juice has been employed for cleaning machete and knife blades

and, with sand, for scrubbing boat decks.

Animal

Feed: Pineapple crowns are sometimes fed to horses if not needed for

planting. Final pineapple waste from the processing factories may be

dehydrated as "bran" and fed to cattle, pigs and chickens. "Bran'' is

also made from the stumps after bromelain extraction. Expendable plants

from old fields can be processed as silage for maintaining cattle when

other feed is scarce. The silage is low in protein and high in fiber

and is best mixed with urea, molasses and water to improve its

nutritional value.

In 1982, public concern in Hawaii was aroused

by the detection of heptachlor (a carcinogen) in the milk from cows fed

"green chop" leaves from pineapple plants that had been sprayed with

the chemical to control the ants that distribute mealybugs. There is

supposed to be a one year lapse to allow the heptachlor to become more

dilute before sprayed plants are utilized for feed.

Folk Medicine:

Pineapple juice is taken as a diuretic and to expedite labor, also as a

gargle in cases of sore throat and as an antidote for seasickness. The

flesh of very young (toxic) fruits is deliberately ingested to achieve

abortion (a little with honey on 3 successive mornings); also to expel

intestinal worms; and as a drastic treatment for venereal diseases. In

Africa the dried, powdered root is a remedy for edema. The crushed rind

is applied on fractures and the rind decoction with rosemary is applied

on hemorrhoids. Indians in Panama use the leaf juice as a purgative,

emmenagogue and vermifuge.

Ornamental Value

The

pineapple fruit with crown intact is often used as a decoration and

there are variegated forms of the plant universally grown for their

showiness indoors or out. Since 1963, thousands of potted, ethylene

treated pineapple plants with fruits have been shipped annually from

southern Florida to northern cities as indoor ornamentals.

|

|