From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Sapodilla

Manilkara

zapota van

Royen

Manilkara achras

Fosb.

Manilkara zapotilla

Gillys

SAPOTACEAE

One of the most interesting and desirable of all tropical fruit

trees, the sapodilla, a member of the family Sapotaceae, is now known

botanically as Manilkara zapota van Royen (syns. M. achras Fosb., M.

zapotilla Gilly; Achras sapota L., A. zapota L.; Sapota achras Mill.).

Among

numerous vernacular names, some of the most common are: baramasi

(Bengal and Bihar, India); buah chiku (Malaya); chicle (Mexico); chico

(Philippines, Guatemala, Mexico); chicozapote (Guatemala, Mexico,

Venezuela); chikoo (India); chiku (Malaya, India); dilly (Bahamas;

British West Indies); korob (Costa Rica); mespil (Virgin Islands);

mispel, mispu (Netherlands Antilles, Surinam); muy (Guatemala);

muyozapot (El Salvador); naseberry (Jamaica; British West Indies);

neeseberry (British West Indies; nispero (Puerto Rico, Central America,

Venezuela); nispero quitense (Ecuador); sapodilla plum (India); sapota

(India); sapotí (Brazil); sapotille (French West Indies);

tree

potato (India); Ya (Guatemala; Yucatan); zapota (Venezuela); zapote

(Cuba); zapote chico (Mexico; Guatemala); zapote morado (Belize);

zapotillo (Mexico).

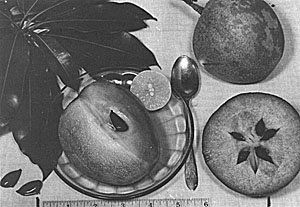

Fig. 107: The sapodilla (M. zapota) is

sweet, luscious, practical and borne abundantly by a handsome, drought-

and wind-resistant tree.

Description

The

sapodilla is a fairly slow-growing, long-lived tree, upright and

elegant, distinctly pyramidal when young; to 60 ft (18 m) high in the

open but reaching 100 ft (30 m) when crowded in a forest. It is strong

and wind-resistant, rich in white, gummy latex. Its leaves are highly

ornamental, evergreen, glossy, alternate, spirally clustered at the

tips of the forked twigs; elliptic, pointed at both ends, firm, 3 to 4

1/2 in (7.5-11.25 cm) long and 1 to 1 1/2 in (2.5-4 cm) wide. Flowers

are small and bell-like, with 3 brown-hairy outer sepals and 3 inner

sepals enclosing the pale-green corolla and 6 stamens. They are borne

on slender stalks at the leaf bases. The fruit may be nearly round,

oblate, oval, ellipsoidal, or conical; varies from 2 to 4 in (5-10 cm)

in width. When immature it is hard, gummy and very astringent. Though

smooth-skinned it is coated with a sandy brown scurf until fully ripe.

The flesh ranges in color from yellowish to light- or dark-brown or

sometimes reddish-brown; may be coarse and somewhat grainy or smooth;

becomes soft and very juicy, with a sweet flavor resembling that of a

pear. Some fruits are seedless, but normally there may be from 3 to 12

seeds which are easily removed as they are loosely held in a whorl of

slots in the center of the fruit. They are brown or black, with one

white margin; hard, glossy; long-oval, flat, with usually a distinct

curved hook on one margin; and about 1/4 in (2 cm) long.

Origin and Distribution

The

sapodilla is believed native to Yucatan and possibly other nearby parts

of southern Mexico, as well as northern Belize and Northeastern

Guatemala. In this region there were once 100,000,000 trees. The

species is found in forests throughout Central America where it has

apparently been cultivated since ancient times. It was introduced long

ago throughout tropical America and the West Indies, the Bahamas,

Bermuda, the Florida Keys and the southern part of the Florida

mainland. Early in colonial times, it was carried to the Philippines

and later was adopted everywhere in the Old World tropics. It reached

Ceylon in 1802.

Cultivation is most extensive in coastal India

(Maharastra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Madras and Bengal States), where

plantations are estimated to cover 4,942 acres (2,000 ha), while Mexico

has 3,733.5 acres (1,511 ha) devoted to the production of fruit (mainly

in the states of Campeche and Veracruz) and 8,192 acres (4,000 ha)

primarily for extraction of chicle (see under "Other Uses") as well as

many dooryard and wild trees. Commercial plantings prosper in Sri

Lanka, the Philippines, the interior valleys of Palestine, as well as

in various countries of South and Central America, including Venezuela

and Guatemala.

Cultivars

In

most areas, types are distinguished merely by shape, as 'Round' and

'Oval' in Saharanpur, India. Several named cultivars are grown for

commercial or home use in western and southern India: 'Kalipatti',

small, early, high quality; 'Calcutta

Special', large, late;

'Pilipatti',

small, midseason to late; 'Bhuripatti',

small, midseason;

'Jumakhia',

small, in clusters, late; 'Mohan

Gooti', small, midseason,

not very sweet; 'Kittubarti',

very small, ridged, very sweet;

'Kittubarti

Big', large, but of inferior quality; 'Cricket Ball', very

large, with crisp, granular, very sweet flesh but not distinctive in

flavor; 'Dwarapudi',

similar, but not quite as big, sweet and very

popular; 'Bangalore',

large, ridged, and 'Vavivalasa'

are oval and

popular in the Circars but are only medium-sweet and bear poorly.

Other

prominent cultivars in India are 'Jonnavalosa-I',

of medium size,

pale-fleshed, sweet; 'Jonnavalosa-Il',

of medium size, ridged, with

yellowish-pink flesh, sweet but not agreeable in flavor; 'Jonnavalosa

Round', large, ridged, with cream-colored flesh, very

sweet;

'Gauranga',

small, lop-sided, ridged, very sweet, bears heavily;

'Ayyangar',

large, very thick-skinned, sweet, rose-scented;

'Thagarampudi',

of medium size, thin-skinned, very sweet; 'Oaka',

small, rounded to oval, of good flavor and popular. Among the

lesser-known are 'Badam',

'Bhuri', 'Calcutta Round', 'CO. 1' ('Cricket

Ball' X 'Long Oval'), 'Dhola

diwani', 'Fingar',

'Gavarayya',

'Guthi',

'Kali', and 'Vanjet'.

A dwarf type called 'Pot'

bears early and can be maintained as a pot specimen for 10 years.

Henry

Pittier, in 1914, described what he deemed a "remarkable variety"

called nispero de monte at Patiño, Panama. The trees do not

exceed 26 ft (8 m) in height and bear small, oblate fruits in dense

clusters.

In Indonesia, sapodillas are classed in two main groups:

1) Sawo maneela, normal-size trees having narrow, pointed leaves; and

2) Sawo apel, low, shrublike trees, with oblong leaves broadest above

the middle. Belonging to group #1 are the common cultivars 'Sawo

betawi' (fruit large, in clusters of 2-4, popular,

perishable, ripening

in 3 days from picking); 'Sawo

koolon' (fruit large, solitary, thick

skinned, with firm flesh, shipping well); 'Sawo madja' (large,

with

persistent scurf, pulp of fine texture, sweet with an acid tang).

Belonging to group #2 are 'Sawo

apel bener' (fruits small in clusters

of 3-6, thick-skinned); 'Sawo

apel klapa' (fruits medium-size, with

persistent scurf). Some others are little grown because the fruits are

either very small, too sandy, too gummy, or too dry.

In Mexico, some superior selections are known merely as 'SCH-02','SCH-03','SCH-07', 'SCH-08',

and 'SCH-28'.

In

Florida, seedling selections of high quality have been named and

vegetatively reproduced. The first of these was 'Russell' from

Islamorada in the Florida Keys, named and propagated by R.H.

Fitzpatrick. It is nearly round, up to 4 in (10 cm) in diameter and

length, brown-scurfy with gray patches, and luscious, reddish flesh. It

is not a dependable bearer.

The second, 'Prolific',

a seedling grown

at the Agricultural Research and Education Center, Homestead, and

released in 1941, is round-conical, 2 1/2 to 3 1/2 in (6.25-9 cm) long

and broad, with smooth, pinkish-tan flesh. The skin is lighter than

that of the 'Russell' and tends to lose much of the scurf as it ripens.

The tree bears early, consistently and heavily. Of later selection,

'Modello' is

a good quality fruit but not a heavy producer; 'Seedless'

yields poorly; 'Brown

Sugar' is a good, regular, high yielder; handles

and keeps well.

Some introduced cultivars being tested in Florida

include: 'Boetzberg',

'Larsen', 'Morning Star', 'Jamaica 8', and

'Jamaica 10'.

'Tikal', a

recent seedling selection, seems very

promising. It is light-brown, elliptic to conical, much smaller than

'Prolific', but of excellent flavor and comes into season very early.

Several cultivars not recommended because of low yield in southern

Florida are 'Addley',

'Adelaide', 'Big Pine Key', 'Black', 'Jamaica No.

4', 'Jamaica No. 5', 'Martin' and 'Saunders'.

In 1951, in Jamaica, I

visited an English gentleman who had a very special sapodilla tree

which bore great quantities of tiny sapodillas, no more than 1 1/2 in

(4 cm) in diameter. They were all seedless and he served them chilled,

whole.

In the Philippines, selected cultivars, 'Ponderosa', 'Java',

'Sao Manila', 'Native', 'Formosa', 'Rangel', and the 'Prolific' from

Florida are maintained by the Bureau of Plant Industry for propagation

and distribution to farmers. 'Sao

Manila' fruits mature in 190 days and

ripen 3 to 5 days after picking.

Hybridization studies have been conducted in India.

Climate

The

sapodilla grows from sea level to 1,500 ft (457 m) in the Philippines,

up to 4,000 ft (1,220 m) in India, to 3,937 ft (1,200 in) in Venezuela,

and is common around Quito, Ecuador, at 9,186 ft (2,800 m). It is not

strictly tropical, for mature trees can withstand temperatures of

26º to 28º F (-3.33º to -2.2º C)

for several hours.

Young trees are tenderer and apt to be killed by 30º F

(-1.11º C) unless the stem is banked with sand or wrapped with

straw and burlap during the cold spell. A number of sapodilia trees

have lived for a few years in California without fruiting and then have

succumbed to cold. Cool nights are considered a constant limiting

factor. However, I have learned of one tree in a protected location in

the Sacramento Valley that has survived for many years, reaching a

large size and fruiting regularly. The sapodilla seems equally at home

in humid and relatively dry atmospheres.

Soil

The

sapodilla grows naturally in the calcareous marl and disintegrated

limestone of its homeland, therefore it should not be surprising that

it is so well adapted to southern Florida and the Florida Keys.

Nevertheless, it flourishes also in deep, loose, organic soil, or on

light clay, diabase, sand or lateritic gravel. Good drainage is

essential, the tree bearing poorly in low, wet locations. It is highly

drought-resistant, can stand salt spray, and approaches the date palm

in its tolerance of soil salinity, rated as ECe 14.20.

Propagation

Seeds

remain viable for several years if kept dry. The best seeds are large

ones from large fruits. They germinate readily but growth is slow and

the trees take 5 to 8 years to bear. Since there is great variation in

the form, quality and yield of fruits from seedling trees, vegetative

propagation has long been considered desirable but has been hampered by

the gummy latex.

In India, several methods are practiced: grafting,

inarching, ground-layering and air-layering. Grafts have been

successful on several rootstocks: sapodilla, Bassia latifolia, B.

longifolia, Sideroxylon dulcificum and Mimusops hexandra.

The last has

been particularly successful, the grafts growing vigorously and

fruiting heavily.

In Florida, shield-budding, cleft-grafting and

side-grafting were moderately successful but too slow for large-scale

production. An improved method of side-grafting was developed using

year-old seedlings with stems 1/4 in (6 mm) thick. The scion (young

terminal shoot) was prepared 6 weeks to several months in advance by

girdling and defoliating. Just before grafting the rootstock was scored

just above the grafting site and the latex "bled" for several minutes.

After the stock was notched and the scion set in, it was bound with

rubber and given a protective coating of wax or asphalt. The scion

started growing in 30 days and the rootstock was then beheaded. Some

years later, further experiments showed that better results were

obtained by omitting the pre-conditioning of the scion and the bleeding

of the latex. The operator must work fast and clean his knife

frequently. The scions are veneer-grafted and then completely covered

with plastic, allowing free gas exchange while preventing dehydration.

Success is deemed most dependent on season: the 2 or 3 months of late

summer and early fall.

In the Philippines, terminal shoots are

completely defoliated 2 to 3 weeks before grafting onto rootstock which

has been kept in partial shade for 2 months. However, inarching is

there considered superior to grafting, giving a greater percentage of

success. Homeowners often find air-layering easier and more successful

than grafting, and air-layered trees often begin bearing within 2 years

after planting.

In India, 50% success has been realized in

top-working 20-year-old trees--cutting back to 3 1/2 ft (1 m) from the

ground and inserting scions of superior cultivars.

Culture

Seedlings for grafting are best grown in full

sun, kept moist and fertilized with 8-4-8 N P K every 45 days.

Trees set out in commercial groves should be spaced 30 to 45 ft (9-13.5

m) apart each way.

In

India, the plants are placed in deep, pre-fertilized pits and manured

twice a year, sometimes with the addition of castor bean meal or

residue of neem seed (Azadirachta indica A. Juss.), wood ash and/or

ammonium sulfate. In an experiment at Marathwada Agricultural

University, Parbhani, India, with 8-year-old trees planted at 12 m,

application of 28 oz (800 g) N/tree increased trunk size and number and

weight of fruits. Combined application of this amount of N plus 6 1/4

oz (176 g) P and 5 3/4 oz (166 g) K/tree gave the highest fruit yield.

Fertilizer experiments over a period of 25 years at Gujarat

Agricultural University revealed that N alone increases yield by 70%, a

combination of N and P elevates yield by 90%, and combined N and K,

128%, over that of control (unfertilized) trees. Of course, optimum

nutrient formulas depend on the character of the soil. In South

Florida's limestone a mixed fertilizer of N, P, K, Mg in a 4-7-5-3

ratio is recommended in spring, summer and fall.

Most mature

sapodilla trees receive no watering, but irrigation in dry seasons will

increase productivity. In some parts of India, brackish or saline water

is sometimes used to reduce vegetative growth and promote fruiting.

Season

The

fruits mature 4 to 6 months after flowering. In the tropics, some

cultivars bear almost continuously. In India, the main season is from

December to March. The trees bear from May to September in Florida,

with the peak of the crop in June and July. In Mexico, there are two

peak seasons: February-April and October-December.

Harvesting

Most

people find it difficult to tell when a sapodilla is ready to pick.

With types that shed much of the "sand" on maturity, it is relatively

easy to observe the slight yellow or peach color of the ripe skin, but

with other types it is necessary to rub the scurf to see if it loosens

readily and then scratch the fruit to make sure the skin is not green

beneath the scurf. If the skin is brown and the fruit separates from

the stem easily without leaking of the latex, it is fully mature though

still hard and must be kept at room temperature for a few days to

soften. It is best to wash off the sandy scurf before putting the fruit

aside to ripen. It should be eaten when firm-soft, not mushy.

In the

Bahamas, children bury their "dillies" in potholes in the limestone to

ripen, or the fruits may be wrapped in sweaters or other thick material

and put in drawers to hasten softening. Fruits picked immature will

shrivel as they soften and will be of inferior quality, sometimes with

small pockets of gummy latex.

In commercial groves, it is judged

that when a few fruits have softened and fallen from the tree, all the

full-grown fruits may be harvested for marketing. If in any doubt, the

grower should cut open a few fruits to make sure the seeds are black

(or very dark-brown). Pickers should use clippers or picking poles with

bag and sharp notch at the peak of the metal frame to cut the fruit

stem.

In India, the fruits are spread out in the shade to allow any

latex at the stem end to dry before packing. The fruits ship well with

minimal packing.

Yield

The

'Prolific' sapodilla yields 6 to 9 bushels per tree annually; or, 200

to 450 lbs (90 to 180 kg). 'Brown Sugar' yields 5 to 8 bushels. In

India, it is said that a productive tree will bear 1,000 fruits in its

10th year and the yield increases steadily. At 30-35 years of age, the

tree should produce 2,500 to 3,000 fruits annually. A great deal

depends on the cultivar. A 10-year-old 'Oval' tree gave 1,158 fruits

weighing 184 lbs (128.8 kg), while a 10-year-old 'Cricket Ball' bore

353 fruits weighing 112 lbs (50 kg). Hand-pollination has been found to

increase fruit set.

Keeping Quality and Storage

Mature,

hard sapodillas will ripen in 9 to 10 days and rot in 2 weeks at normal

summer temperature and relative humidity. More than 50 years ago,

sapodillas were shipped from Java to Holland, held at

40º-50º

F (4.44-10º C) for 3 days, and they ripened satisfactorily

after

arrival. They were smoked over burning straw for a few hours before

packing. Storage trials in Malaya demonstrated that mature, hard

sapodillas stored at 68º F (20º C) win ripen in 10

days and

remain in good condition for another 5 days. In Venezuela, mature

fruits held at 68º F (20º C) and 90% relative

humidity were

in excellent condition at the end of 23 days. Lower temperatures, in

efforts to prolong storage life, seriously retard ripening and lower

fruit quality.

Low relative humidity causes shriveling and

wrinkling. Humid conditions promote sogginess. If long storage is

necessary, the fruits may be kept at 59º-68º F

(15º-20º C) in a controlled atmosphere of 85-90%

relative

humidity, 5-10% (v/v) CO2,with total removal Of C2H4 to delay ripening.

Firm-ripe

sapodillas may be kept for several days in good condition in the home

refrigerator. At 35º F (1.67º C), they can be kept

for 6

weeks. Fully ripe fruits frozen at 32º F (0º C) keep

perfectly for 33 days.

Pests and Diseases

In

general, the sapodilla tree remains supremely healthy with little or no

care. In India, it is sometimes attacked by a bark-borer, Indarbela

(Arbela)

tetraonis. Mealybugs may infest tender shoots and deface the

fruits. A galechid caterpillar (Anarsia)

has caused flower buds and

flowers to dry up and fall.

In Indonesia, caterpillars of Tarsolepis

remicauda may completely defoliate the tree. A caterpillar, Nephopteryx

engraphella, feeds on the leaves, flower buds and young fruits in parts

of India. The ripening and overripe fruits are favorite hosts of the

Mediterranean, Caribbean, Mexican and other fruit flies.

Various

scales, including Howardia

biclavis, Pulvinaria (or Chloropulvinaria)

psidii, Rastrococcus iceryoides, and pustule scale, Asterolecanium

pustulans Ckll., may lead to black sooty mold caused by

the fungus

Capnodium

sp. on stems, foliage and fruits. In some years, during

winter and spring in Florida, a rust (possibly Uredo sapotae) may

affect the foliage of some cultivars. A leaf spot (Septoria sp.) has

caused defoliation in a few locations. The moth of a leaf miner

(Acrocercops gemoniella)

is active on young leaves. Other minor enemies

have been occasionally observed.

In India, it may be necessary to spread nets over the tree to protect

the fruits from fruit bats.

Food Uses

Generally,

the ripe sapodilla, unchilled or preferably chilled, is merely cut in

half and the flesh is eaten with a spoon. It is an ideal dessert fruit

as the skin, which is not eaten, remains firm enough to serve as a

"shell". Care must be taken not to swallow a seed, as the protruding

hook might cause lodging in the throat. The flesh, of course, may be

scooped out and added to fruit cups or salads. A dessert sauce is made

by peeling and seeding ripe sapodillas, pressing the flesh through a

colander, adding orange juice, and topping with whipped cream.

Sapodilla flesh may also be blended into an egg custard mix before

baking.

It was long proclaimed that the fruit could not be cooked or

preserved in any way, but it is sometimes fried in Indonesia and, in

Malaya, is stewed with lime juice or ginger. I found that Bahamians

often crush the ripe fruits, strain, boil and preserve the juice as a

sirup. They also add mashed sapodilla pulp to pancake batter and to

ordinary bread mix before baking.

My own experiments showed that a

fine jam could be made by peeling and stewing cut-up ripe fruits in

water and skimming off a green scum that rises to the surface and

appears to be dissolved latex, then adding sugar to improve texture and

sour orange juice and a strip of peel to offset the increased

sweetness. Skimming until all latex scum is gone is the only way to

avoid gumminess. Cooking with sugar changes the brown color of the

flesh to a pleasing red.

One lady in Florida developed a recipe for

sapodilla pie. She peeled the ripe fruits, cut them into pieces as

apples are cut, and filled the raw lower crust, sprinkled 1/2 cup of

raisins over the fruit, poured over evenly 1/2 cup of 50-50 lime and

lemon juice to prevent the sapodilla pieces from becoming rubbery, and

then sprinkled evenly 1/2 cup of granulated sugar. After covering with

the top crust and making a center hole to release steam, she baked for

40 minutes at 350º F (176.67º C). In India, it has

been shown

that ripe fruits can be peeled and sliced, packed in metal cans, heated

for 10 minutes at 158º F (70º C), then treated for 6

minutes

at a vacuum of 28 in Hg, vacuum double-seamed, and irradiated with a

total dose of 4 x 105 rads at room temperature. This process provides

an acceptable canned product.

Ripe sapodillas have been successfully

dried by pretreatment with a 60% sugar solution and osmotic dehydration

for 5 hours, and the product has retained acceptable quality for 2

months.

Mr. Edward Smith of Crescent Place, Trinidad, made sapodilla

wine and told me that it was very good. Young leafy shoots are eaten

raw or steamed with rice in Indonesia, after washing to eliminate the

sticky sap.

Food Value

Immature

sapodillas are rich in tannin (proanthocyanadins) and very astringent.

Ripening eliminates the tannin except for a low level remaining in the

skin.

Analyses of 9 selections of sapodillas from southern Mexico

showed great variation in total soluble solids, sugars and ascorbic

acid content. Unfortunately, the fruits were not peeled and therefore

the results show abnormal amounts of tannin contributed by the skin.

Moisture

ranged from 69.0 to 75.7%; ascorbic acid from 8.9 to 41.4 mg/100 g;

total acid, 0.09 to 0.15%; pH, 5.0 to 5.3; total soluble solids,

17.4º to 23.7º Brix; as for carbohydrates, glucose

ranged

from 5.84 to 9.23%, fructose, 4.47 to 7.13%, sucrose, 1.48 to 8.75%,

total sugars, 11.14 to 20.43%, starch, 2.98 to 6.40%. Tannin content,

because of the skins, varied from 3.16 to 6.45%.

Toxicity

The

seed kernel (50% of the whole seed) contains 1% saponin and 0.08% of a

bitter principle, sapotinin. Ingestion of more than 6 seeds causes

abdominal pain and vomiting.

Other Uses

Chicle:

A major by-product of the sapodilla tree is the gummy latex called

"chicle", containing 15% rubber and 38% resin. For many years it has

been employed as the chief ingredient in chewing gum but it is now in

some degree diluted or replaced by latex from other species and by

synthetic gums.

Chicle is tasteless and harmless and is obtained by

repeated tapping of wild and cultivated trees in Yucatan, Belize and

Guatemala. It is coagulated by stirring over low fires, then poured

into molds to form blocks for export. Processing consists of drying,

melting, elimination of foreign matter, combining with other gums and

resins, sweeteners and flavoring, then rolling into sheets and cutting

into desired units.

The dried latex was chewed by the Mayas and was

introduced into the United States by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana

about 1866 while he was on Staten Island awaiting clearance to enter

this country. He had a supply in his pocket for chewing and gave a

piece to the son of Thomas Adams. The latter at first considered the

possibility of using it to make dentures, then decided it was useful

only as a masticatory. He found he could easily incorporate flavoring

and thus soon launched the chicle-based chewing-gum industry. In 1930,

at the peak of production, nearly 14,000,000 lbs (6,363,636 kg) of

chicle were imported.

Efforts have been made to extract chicle from

the leaves and unripe fruit but the yield is insufficient. It has been

estimated that 3,200 leaves would be needed to produce one pound

(0.4535 kg) of gum.

Among miscellaneous uses: the latex is employed

as birdlime, as an adhesive in mending small articles in India; it has

been utilized in dental surgery, and as a substitute for gutta percha.

The Aztecs used it for modeling figurines.

Timber:

Sapodilla wood is

strong and durable and timbers which formed lintels and supporting

beams in Mayan temples have been found intact in the ruins. It has also

been used for railway crossties, flooring, native carts, tool handles,

shuttles and rulers. The red heartwood is valued for archer's bows,

furniture, bannisters, and cabinetwork but the sawdust irritates the

nostrils. Felling of the tree is prohibited in Yucatan because of its

value as a source of chicle.

Bark: The tannin-rich bark is used by Philippine fishermen to tint

their sails and fishing lines.

Medicinal

Uses: Because of the tannin content, young fruits are

boiled and the

decoction taken to stop diarrhea. An infusion of the young fruits and

the flowers is drunk to relieve pulmonary complaints. A decoction of

old, yellowed leaves is drunk as a remedy for coughs, colds and

diarrhea. A "tea" of the bark is regarded as a febrifuge and is said to

halt diarrhea and dysentery. The crushed seeds have a diuretic action

and are claimed to expel bladder and kidney stones. A fluid extract of

the crushed seeds is employed in Yucatan as a sedative and soporific. A

combined decoction of sapodilla and chayote leaves is sweetened and

taken daily to lower blood pressure. A paste of the seeds is applied on

stings and bites from venomous animals. The latex is used in the

tropics as a crude filling for tooth cavities.

|

|