Tamarillos

are small, shrubby trees that fruit on current season’s growth. The

yield, fruit size and season of maturity can all be readily manipulated

by the time and severity of pruning.

The results

outlined in this article come from an unpublished pruning trial

conducted by Drs Greg Pringle, Kevin Patterson and Grant Thorp (now of

HortResearch) in Kerikeri during the early 1980s, and are used with

their permission.

Plate

1: Moderately pruned tamarillo in a Katikati orchard

The

basic pruning strategy for tamarillos is to maintain a sturdy framework

with new growth originating from the previous season’s wood.

This

sturdy framework is important due to the brittle nature of tamarillo

wood. Compact, sturdy trees are less prone to breakage than leggy

trees, and they can also be picked satisfactorily from the ground.

It

is also important to cut back into the previous season’s wood when

pruning, as cutting into older wood gives a much more variable

response, usually being comparatively unfruitful. It is normal practice

to remove dead or broken branches at the annual spring pruning.

The

time of pruning influences the time at which the following season’s

crop will mature. After pruning, there is a period when it appears as

if nothing is happening before the new growth starts. This period is a

little longer under the lower temperatures that generally prevail in

early spring as compared to those likely to be experienced some weeks

later in mid to late spring. However, as new season’s flowers are

produced on new season’s growth, the new growth must occur before

flowers are produced, and this is influenced by the time of pruning.

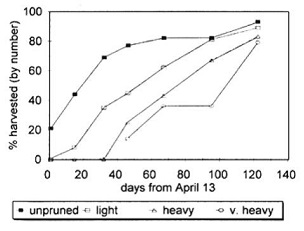

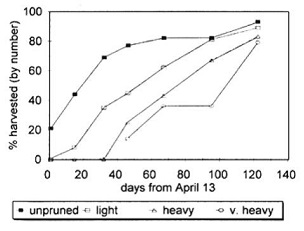

It

takes approximately 20-26 weeks from fruit set to maturity, so the

earlier the fruit is set, the earlier the harvesting season is likely

to be. So early season pruning leads to an early harvesting season and

late pruning leads to a late harvesting season (Figure 4). The severity

of pruning influences the potential yield, fruit size and season of

maturity. A general principle of pruning is that the harder the cut,

the more vigorous the vegetative response is likely to be.

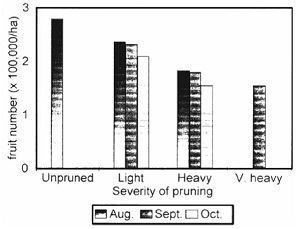

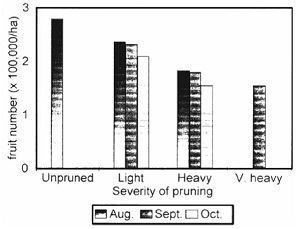

The

heaviest and earliest crops will be produced by unpruned trees (see

Figure 1). Light pruning gives rise to weak regrowth that branches and

sets flowers quickly and in turn leads to reasonably heavy and early

maturing crops.

Hard pruning, on the other hand, gives

rise to more vigorous regrowth, provided the tree is not cut back to

old wood. Some of these regrowths may be so vigorous they need to be

pinched out at the appropriate height to cause branching and flower

production in a tree manageable from the ground. Such vigorous regrowth

takes longer to reach the stage where flowers are produced and so has

the tendency to delay the harvest season, as compared to more moderate

pruning.

1.

Total

yield from mature tamarillo trees with pruning to different degrees and

at

different times (August 1, September 8 and October 15).

2.

Fruit

numbers from mature tamarillo trees under the same set of pruning

regimes.

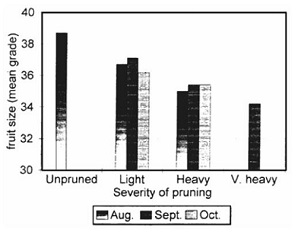

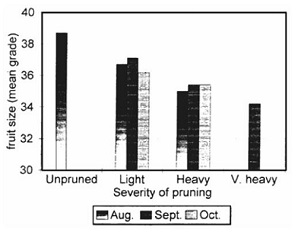

Fruit

size is also affected by the severity of pruning (Figure 3). Unpruned

trees produce many fruit on weak multi-branches shoots and this gives

the potential for high fruit numbers at the expense of fruit size.

At

the other end of the scale, hard pruning leads to a small number of

more vigorous and substantial shoots which tend to produce lower

numbers of large fruit. Moderate pruning comes somewhere in between.

The response to pruning in fruit size is, of course, limited by the

genetics of the tree. It is not possible to get very large fruit from a

small fruited variety simply by hard pruning. They can only be as big

as their genetics dictate.

Water shoots have thick

green stems with long internodes. They tend to originate either from

the main trunk of from deep within the canopy. They bear few fruit and

only serve to direct the plant’s resources away from the remaining

crop. As such, they should be pruned out completely as they arise

during the growing season.

Time and severity of pruning can then be used

as a means of manipulating the yield and season of the crop as well as

fruit size.

There

may be many reasons for a grower larger fruit size. Each individual

case must be judged on its own merits and treated accordingly.

These

variations in pruning can be used to get a comparatively steady, but

very long harvesting season from April to November by pruning different

blocks over an extended period of time from early spring to early

summer. They could also be used to get either an early or late crop for

economic, management or other reasons.

Plate 2. Moderately pruned tamarillo in a Tauranga orchard

showing the quantity of growth removed.

Returns

for tamarillos, like other seasonal crops, tend to be highest when

supplies are short at the beginning or end of the season. So an early

harvest, where a significant percentage of the crop is harvested by the

end of May , can be worthwhile.

However, to get the

most out of a very early season crop requires a lot of time in select

picking the earliest fruit to get them onto the market as early as

possible.

Over the years, it has been noted that

returns from the New Zealand market tend to be at their lowest in June

through to August, when supplies are normally heaviest. From September

onwards, prices can be expected to rise as supplies dwindle.

On

the New Zealand market, large fruit will normally get a better return

than medium or small fruit. However, with the high returns early in the

season, earliness could be expected to be more important than fruit

size at the very start of the season.

Export

requirements seem to be for a reasonable, medium-sized fruit, rather

than the very largest. This must be taken into the equation by growers

producing for export.

Plate 3. The response to hard pruning is vigorous growth

with a moderate number of large-sized fruit.

It

is always a good policy to keep in touch with the chosen exporter over

the specifications required, including fruit size, and if necessary

adjust the orchard management to meet them.

On sites with a greater

risk of getting a winter frost, it would be desirable to have most of

the fruit off early, before the high risk period in June and July.

It

may also be that tamarillos have to be worked into a mixed orchard

calendar and manipulating the harvest time to suit is a worthwhile

practice.

Where a grower deals with a lot of kiwifruit harvesting

from sometime in April to early June, an early tamarillo crop would be

a complication, as it could also be for growers producing a feijoas or

passionfruit. Conversely, with satsuma and Clementine mandarins that

can run on through into August, it would be more convenient to get the

tamarillos in early and be well through their season before the

mandarins get into full swing.

Fig. 3.

Mean

fruit size from mature tamarillo trees under various

pruning regimes. Note that higher graes equate to smaller fruit;

the very heavy pruning treatment had the largest fruit.

Yield,

fruit number, fruit size and season of maturity of tamarillos are all

affected by the timing and severity of pruning. The earliest and

heaviest yields of the smallest fruit are produced on unpruned trees.

The largest and latest maturing fruit are produced by pruning hard and

late. There are no overall recommendations, but each grower can take

this basic information and use it how it best fits into the overall

management of the orchard.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative

progression of harvest season from

September pruned trees with different degrees of pruning.

The last harvest (day 122) corresponds to August 13.

Based

on an article in the August 1996 issue of ‘The Orchardist’, magazine of

the New Zealand Fruitgrowers Federation (PO Box 2175, Wellington, New

Zealand).