Publication

from Agroforestree Database: a tree reference and selection guide

version 4.0

by C. Orwa, A. Mutua, R. Kindt, R. Jamnadass and S. Anthony

Tamarindus indica L.

Local Names: Afrikaans

(tamarinde); Amharic (humer, roka); Arabic (ardeib, aradeib); Bemba

(mushishi); Bengali (anbli, amli, nuli, tintul, tintiri, tentul); Burmese

(magyee, majee-pen); Creole (tamarenn); English (madeira mahogany, Indian

date, tamarind tree); Filipino (sampalok, kalamagi, salomagi); French

(tamarinde, tamarinier); Fula (jammeh, jammi, dabe); Gujarati

(ambali, amali); Hindi (tentul, chinta, anbli, tamrulhindi, amli, imli);

Indonesian (asam, asam jawa, tambaring); Khmer (khoua me, ‘am’pül,ampil);

Lao (Sino-Tibetan) (mak kham, khaam); Luganda (mukoge); Malay (asam

jawa); Mandinka (tomi, timbingo, timbimb, tombi); Nepali (imli); Nyanja

(mwemba); Sanskrit (amlica, tintiri); Sinhala (siyambala); Somali

(rakhai, hamar); Spanish (tamarin, tamarindo); Swahili (msisi, mkwaju);

Tamil (amilam, puli, puliamavam); Thai (bakham, makham, somkham); Tigrigna

(humer); Tongan (musika); Trade name (tamarind); Urdu (imli);

Vietnamese (trai me, me); Wolof (daharg, dakah, dakhar, ndakhar)

Family: Fabaceae - Caesalpinioideae

Botanic

Description

Tamarindus indica is a

large evergreen tree up to 30 m tall, bole usually 1-2 m, up to 2 m

diameter; crown dense, widely spreading, rounded; bark rough, fissured,

greyish-brown.

Leaves alternate, compound, with 10-18 pairs of

opposite leaflets; leaflets narrowly oblong, 12-32 x 3-11 mm, petiole

and rachis finely haired, midrib and net veining more or less

conspicuous on both surfaces; apex rounded to almost square, slightly

notched; base rounded, asymmetric, with a tuft of yellow hairs; margin

entire, fringed with fine hairs. Stipules present, falling very early.

Flowers

attractive pale yellow or pinkish, in small, lax spikes about 2.5 cm in

width. Flower buds completely enclosed by 2 bracteoles, which fall very

early; sepals 4, petals 5, the upper 3 well developed, the lower 2

minute.

Fruit a pod, indehiscent, subcylindrical, 10-18 x 4 cm,

straight or curved, velvety, rusty-brown; the shell of the pod is

brittle and the seeds are embedded in a sticky edible pulp. Seeds 3-10,

approximately 1.6 cm long, irregularly shaped, testa hard, shiny and

smooth.

As the dark brown pulp made from the fruit resembles dried

dates, the Arabs called it ‘tamar-u’l-Hind’, meaning ‘date of India’,

and this inspired Linnaeus when he named the tree in the 18th century. Tamarindus is a monospecific genus.

Biology

Flowering generally

occurs in synchrony with new leaf growth, which in most areas is during

spring and summer. The hermaphroditic bisexual flowers are probably

insect pollinated; however, no specific information has been found on

pollinating agents, except that honeybees collect nectar and pollen

from the flowers so, presumably, they contribute to pollination. T. indica

usually starts bearing fruit at 7-10 years of age, with pod yields

stabilizing at approximately 15 years. Fruits are adapted to dispersal

by ruminants; in Southeast Asia, monkeys are among the chief dispersal

agents. Fruit are leathery, nutritive pods that do not dehisce until

they have fallen from the tree, while the seeds are hard and smooth and

therefore hard to chew.

Ecology

T. indica

grows well over a wide range of soil and climatic conditions, occurring

in low-altitude woodland, savannah and bush, often associated with

termite mounds. It prefers semi-arid areas and wooded grassland, and

can also be found growing along stream and riverbanks. It does not

penetrate into the rainforest. Its extensive root system contributes to

its resistance to drought and wind. It also tolerates fog and saline

air in coastal districts, and even monsoon climates, where it has

proved its value for plantations. Young trees are killed by the

slightest frost, but older trees seem more cold resistant than mango,

avocado or lime. A long, well-marked dry season is necessary for

fruiting.

Biophysical

Limits

Altitude: 0-1 500 m, Mean annual temperature : 20-33 deg. C, Mean annual rainfall: 350-2 700 mm

Soil type: It grows in most soils but prefers well-drained deep alluvial soil.

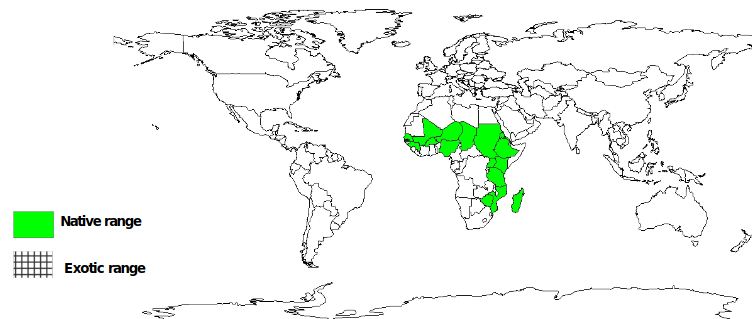

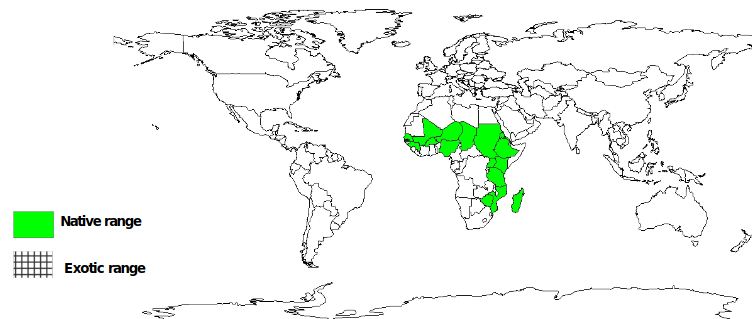

Documented

Species Distribution

Native: Burkina Faso, Central

African Republic, Chad, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Guinea,

Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Madagascar, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria,

Senegal, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda, Zimbabwe

Exotic: Afghanistan,

Australia, Bangladesh, Brazil, Brunei, Cambodia, China, Colombia, Cote

d'Ivoire, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Egypt, Ghana, Guatemala, Haiti,

Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Jamaica, Laos, Liberia, Malaysia,

Mauritania, Mexico, Myanmar, Nepal, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Papua

New Guinea, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Togo, US,

Vietnam, Zambia

The

map above shows countries where the species has been planted. It does

neither suggest that the species can be planted in every ecological

zone within that country, nor that the species can not be planted in

other countries than those depicted. Since some tree species are

invasive, you need to follow biosafety procedures that apply to your

planting site.

Products

Food: The fruit pulp, mixed

with a little salt, is a favourite ingredient of the curries and

chutneys popular throughout India, though most of the tamarind imported

into Europe today comes from the West Indies, where sugar is added as a

preservative. When freshly prepared, the pulp is a light brown colour

but darkens with time; it consists of 8-14% tartaric acid and potassium

bitartrate, and 30-40% sugar. Acidity is caused by the tartaric acid,

which on ripening does not disappear, but is matched more or less by

increasing sugar levels. Hence tamarind is said to be simultaneously

the most acid and the sweetest fruit. The ripe fruit of the sweet type

is usually eaten fresh, whereas the fruits of sour types are made into

juice, jam, syrup and candy. Fruit is marketed worldwide in sauces,

syrups and processed foods. The juice is an ingredient of

Worcestershire Sauce and has a high content of vitamin B (thiamine and

niacin) as well as a small amount of carotene and vitamin C. The

flowers, leaves and seeds can be eaten and are prepared in a variety of

dishes. Tamarind seeds are also edible after soaking in water and

boiling to remove the seed coat. Flour from the seed may be made into

cake and bread. Roasted seeds are claimed to be superior to groundnuts

in flavour.

Fodder: The foliage has a high

forage value, though rarely lopped for this purpose because it affects

fruit yields. In the southern states of India cooked seeds of Tamarind

tree are fed to draught animals regularly.

Apiculture: Flowers are reportedly a good source for honey production.The second grade honey is dark-coloured.

Fuel: Provides good firewood with calorific value of 4 850 kcal/kg, it also produces an excellent charcoal.

Timber: Sapwood is light

yellow, heartwood is dark purplish brown; very hard, durable and strong

(specific gravity 0.8-0.9g/cubic m), and takes a fine polish. It is

used for general carpentry, sugar mills, wheels, hubs, wooden utensils,

agricultural tools, mortars, boat planks, toys, panels and furniture.

In North America, tamarind wood has been traded under the name of

‘madeira mahogany'.

Lipids: An amber coloured seed

oil - which resembles linseed oil - is suitable for making paints and

varnishes and for burning in lamps.

Tannin or

dyestuff: Both

leaves and bark are rich in tannin. The bark tannins can be used in ink

or for fixing dyes. Leaves yield a red dye, which is used to give a

yellow tint to clothe previously dyed with indigo. Ashes from the wood

are used in removing hair from animal hides.

Medicine: The bark is astringent

and tonic and its ash may be given internally as a digestive.

Incorporated into lotions or poultices, the bark may be used to relives

sores, ulcers, boils and rashes. It may also be administered as a

decoction against asthma and amenorrhea and as a febrifuge. Leaf

extracts exhibit anti-oxidant activity in the liver, and are a common

ingredient in cardiac and blood sugar reducing medicines. Young leaves

may be used in fomentation for rheumatism, applied to sores and wounds,

or administered as a poultice for inflammation of joints to reduce

swelling and relieve pain. A sweetened decoction of the leaves is good

against throat infection, cough, fever, and even intestinal worms.

Filtered hot juice of young leaves and a poultice of the flowers are

used for conjunctivitis. The pulp may be used as a massage is used to

treat rheumatism, as an acid refrigerant, a mild laxative and also to

treat scurvy. Powdered seeds may be given to cure dysentery and

diarrhoea.

Other products: The

pulp of the fruit, sometimes mixed with sea-salt, is used to polish

silver, copper and brass in India and elsewhere. The seed contains

pectin that can be used for sizing textiles. Ground, boiled, and mixed

with gum, the seeds produce a strong wood cement. In Africa, tamarind

is a host of one of the wild silkworms (Hypsoides vuillitii).

Services

Shade or shelter:

The extended crown of the tamarind offers shade so that it is used as a

‘rest and consultation tree’ in villages. Because of its resistance to

storms it can also be used as a windbreak. It should be considered,

however, that T. indica is

not very compatible with other plants because of its dense shade, broad

spreading crown and allelopathic effects. It is thus more commonly used

for firebreaks, as no grass will grow under the trees.

Boundary or barrier or support: T. indica could be inserted into a live fence.

Ornamental: The

evergreen habit and the beautiful flowers make it suitable for

ornamental planting in parks, along roads and riverbanks.

Tree

Management

Growth is

generally slow; seedling height increasing by about 60 cm annually. The

juvenile phase lasts up to 4-5 years, or longer. Young trees are pruned

to allow 3-5 well-spaced branches to develop into the main scaffold

structure of the tree. After this, only maintenance pruning is required

to remove dead or damaged wood. Trees generally require minimal care,

but in orchards in Thailand’s central delta, intensive cropping is

practised. This is possible because grafted trees come to bear within

3-4 years. Sweet cultivars are planted and good early crops limit

extensive growth; presumably the high water table, which prevents deep

rooting, also helps to dwarf the trees. Size-control measures include

close spacing (about 500 trees/ha) and pruning to rejuvenate the

fruiting wood. The trees also respond to coppicing and pollarding.

When

establishing a pure plantation, spacing should be at least 13 x 13 m.

Distance can be reduced with vegetatively propagated plants, as they do

not attain the same size as seeded trees. Smaller trees are easier to

harvest. The tree may remain productive until it reaches old age,

yielding up to 150 kg/tree or over 2 t/ha a year.

Germplasm

Management

Seed

storage behaviour is orthodox; no loss in viability during 1 years of

hermetic storage at 4 deg. C; and viability can be maintained for

several years in hermetic storage at 10 deg. C with 7-15% mc. There are

approximately 350-1 000 seeds/kg.

Pests and

Diseases

The most serious pests of the tamarind are scale insects (Aonidiella orientalis, Aspidiotus destructor and Saisetia oleae), mealy-bugs (Nipaecoccus viridis and Planococcus lilacinus), and a borer (Pachymerus gonagra).

Other minor pests in India include lac insects, and bagworms. Beetle

larvae cause damage to branches in Brazil, while in Florida and Hawaii

beetles attack ripe pods. Termites attack the tree in China. Stored

fruit is commonly infested in India. Larvae of the groundnut bruchid

beetle are serious pests that attack the fruit and seed in India. In

some seasons, fruit borers may inflict serious damage to maturing

fruits causing a great reduction in marketable yield.Diseases which

have been reported from India leaf spot, powdery mildews, a sooty

mould, stem disease, stem, root and wood rot, stem canker, a bark

parasite and a bacterial leaf-spot.

Further

Reading

Albrecht J. ed. 1993. Tree seed hand book of Kenya. GTZ Forestry Seed Center Muguga, Nairobi, Kenya.

Anon. 1986. The useful plants of India. Publications & Information Directorate, CSIR, New Delhi, India.

Beentje HJ. 1994. Kenya trees, shrubs and lianas. National Museums of Kenya.

Bein E. 1996. Useful trees and shrubs in Eritrea. Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Nairobi, Kenya.

Bekele-Tesemma

A, Birnie A, Tengnas B. 1993. Useful trees and shrubs for Ethiopia.

Regional Soil Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International

Development Authority (SIDA).

Birnie A. 1997. What tree is that? A beginner's guide to 40 trees in Kenya. Jacaranda designs Ltd.

Coates-Palgrave K. 1988. Trees of southern Africa. C.S. Struik Publishers Cape Town.

Crane E (ed.). 1976. Honey: A comprehensive survey. Bee Research Association.

Dale IR, Greenway PJ. 1961. Kenya trees and shrubs. Buchanan’s Kenya Estates Ltd.

Eggeling. 1940. Indigenous trees of Uganda. Govt. of Uganda.

El-Siddig K, Gunasena HPM, Prasad BA, Pushpakumara DKNG, Ramana KVR, Vijayanand P, Williams JT. 2006. Tamarind Tamarindus indica L. Southampton, UK: Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops. 198p.

Gunasena HPM, Pushpakumara DKNG. 2007. Chapter 12: Tamarind Tamarindus indica

L.: In: Pushpakumara DKNG, Gunasena HPM, Singh VP. 2007 eds.

Underutilized fruit trees in Sri Lanka. World Agroforestry Centre,

South Asia Office, New Delhi, India. p. 352-388.

Hines DA, Eckman K.

1993. Indigenous multipurpose trees for Tanzania: uses and economic

benefits to the people. Cultural survival Canada and Development

Services Foundation of Tanzania.

Hocking D. 1993. Trees for Drylands. Oxford & IBH Publishing Co. New Delhi.

Hong TD, Linington S, Ellis RH. 1996. Seed storage behaviour: a compendium. Handbooks for Genebanks: No. 4. IPGRI.

ICRAF.

1992. A selection of useful trees and shrubs for Kenya: Notes on their

identification, propagation and management for use by farming and

pastoral communities. ICRAF.

Katende AB et al. 1995. Useful trees

and shrubs for Uganda. Identification, Propagation and Management for

Agricultural and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil Conservation Unit

(RSCU), Swedish International Development Authority (SIDA).

Kayastha

BP. 1985. Silvics of the trees of Nepal. Community Forest Development

Project, Kathmandu.Lanzara P. and Pizzetti M. 1978. Simon &

Schuster's Guide to Trees. New York: Simon and SchusterLuna R K. 1997.

Plantation trees. International Book Distributors.

Mbuya LP et al.

1994. Useful trees and shrubs for Tanzania: Identification, Propagation

and Management for Agricultural and Pastoral Communities. Regional Soil

Conservation Unit (RSCU), Swedish International Development Authority

(SIDA).

Noad T, Birnie A. 1989. Trees of Kenya. General Printers, Nairobi.

Parkash

R, Hocking D. 1986. Some favourite trees for fuel and fodder. Society

for promotion of wastelands development, New Delhi, India.

Parrotta JA. 1990. Tamarindus indica L., Tamarind. SO-ITF-SM-30. USDA Forestry Service, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico.

Perry LM. 1980. Medicinal plants of East and South East Asia : attributed properties and uses. MIT Press. South East Asia.

Pushpakumara DKNG, Gunasena HPM. 2006. In: Williams JT, Smith RW, Haq N, Dunsiger Z. eds. Tamarind: Tamarindus Indica. Southampton Centre for Underutilized Crops, Southampton, UK.

Pushpakumara DKNG, Gunasena HPM. 2007. Chapter 12: Tamarind Tamarindus indica

L.: Progress of ACUC-CARP-UP research activities on selected

under-utilized fruit trees in Sri Lanka. Paper presented at the 4th

International Symposium on New Crops held at the University of

Southampton, UK from 2-4 September 2007. 32p.

Sahni KC. 1968. Important trees of the northern Sudan. United Nations and FAO.

Singh RV. 1982. Fodder trees of India. Oxford & IBH Co. New Delhi, India.

|

|