From the book

Fruits of Warm Climates

by Julia F. Morton

Tamarind

Tamarindus indica

LEGUMINOSAE

Of all the fruit trees of the tropics, none is more widely

distributed nor more appreciated as an ornamental than the tamarind,

Tamarindus indica L. (syns. T. occidentalis Gaertn.; T. officinalis

Hook.), of the family Leguminosae. Most of its colloquial names are

variations on the common English term. In Spanish and Portuguese, it is

tamarindo; in French, tamarin, tamarinier, tamarinier des Indes, or

tamarindier; in Dutch and German, tamarinde; in Italian, tamarandizio;

in Papiamiento of the Lesser Antilles, tamarijn. In the Virgin Islands,

it is sometimes called taman; in the Philippines, sampalok or various

other dialectal names; in Malaya, asam jawa; in India, it is tamarind

or ambli, imli, chinch, etc.; in Cambodia, it is ampil or khoua me; in

Laos, mak kham; in Thailand, ma-kharm; in Vietnam, me. The name

"tamarind" with a qualifying adjective is often applied to other

members of the family Leguminosae having somewhat similar foliage.

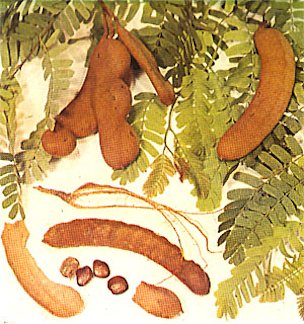

Plate XIV: TAMARIND, Tamarindus indica

Description

The tamarind, a slow-growing, long-lived, massive tree reaches, under

favorable conditions, a height of 80 or even 100 ft (24-30 m), and may

attain a spread of 40 ft (12 m) and a trunk circumference of 25 ft (7.5

m). It is highly wind-resistant, with strong, supple branches,

gracefully drooping at the ends, and has dark-gray, rough, fissured

bark. The mass of bright-green, fine, feathery foliage is composed of

pinnate leaves, 3 to 6 in (7.5-15 cm) in length, each having 10 to 20

pairs of oblong leaflets 1/2 to 1 in (1.25-2.5 cm) long and 1/5 to 1/4

in (5-6 mm) wide, which fold at night. The leaves are normally

evergreen but may be shed briefly in very dry areas during the hot

season. Inconspicuous, inch-wide flowers, borne in small racemes, are

5-petalled (2 reduced to bristles), yellow with orange or red streaks.

The flowerbuds are distinctly pink due to the outer color of the 4

sepals which are shed when the flower opens.

The

fruits, flattish, beanlike, irregularly curved and bulged pods, are

borne in great abundance along the new branches and usually vary from 2

to 7 in long and from 3/4 to 1 1/4 in (2-3.2 cm) in diameter.

Exceptionally large tamarinds have been found on individual trees. The

pods may be cinnamon-brown or grayish-brown externally and, at first,

are tender-skinned with green, highly acid flesh and soft, whitish,

under-developed seeds. As they mature, the pods fill out somewhat and

the juicy, acidulous pulp turns brown or reddish-brown. Thereafter, the

skin becomes a brittle, easily-cracked shell and the pulp dehydrates

naturally to a sticky paste enclosed by a few coarse strands of fiber

extending lengthwise from the stalk. The 1 to 12 fully formed seeds are

hard, glossy-brown, squarish in form, 1/8 to 1/2 in (1.1-1.25 cm) in

diameter, and each is enclosed in a parchmentlike membrane.

Origin and

Distribution

Native

to tropical Africa, the tree grows wild throughout the Sudan and was so

long ago introduced into and adopted in India that it has often been

reported as indigenous there also, and it was apparently from this

Asiatic country that it reached the Persians and the Arabs who called

it "tamar hindi" (Indian date, from the date-like appearance of the

dried pulp), giving rise to both its common and generic names.

Unfortunately, the specific name, "indica", also perpetuates the

illusion of Indian origin. The fruit was well known to the ancient

Egyptians and to the Greeks in the 4th Century B.C.

The tree has

long been naturalized in the East Indies and the islands of the

Pacific. One of the first tamarind trees in Hawaii was planted in 1797.

The tamarind was certainly introduced into tropical America, Bermuda,

the Bahamas, and the West Indies much earlier. In all tropical and

near-tropical areas, including South Florida, it is grown as a shade

and fruit tree, along roadsides and in dooryards and parks. Mexico has

over 10,000 acres (4,440 ha) of tamarinds, mostly in the states of

Chiapas, Colima, Guerrero, Jalisco, Oaxaca and Veracruz. In the lower

Motagua Valley of Guatemala, there are so many large tamarind trees in

one area that it is called "El Tamarindal". There are commercial

plantings in Belize and other Central American countries and in

northern Brazil. In India there are extensive tamarind orchards

producing 275,500 tons (250,000 MT) annually. The pulp is marketed in

northern Malaya and to some extent wherever the tree is found even if

there are no plantations.

Varieties

In some regions

the type with reddish flesh is distinguished from the ordinary

brown-fleshed type and regarded as superior in quality. There are types

of tamarinds that are sweeter than most. One in Thailand is known as

'Makham waan'. One distributed by the United States Department of

Agriculture's Subtropical Horticulture Research Unit, Miami, is known

as 'Manila Sweet'.

Climate

Very young trees should be protected from cold but older trees are

surprisingly hardy. Wilson Popenoe wrote that a large tree was killed

on the west coast of Florida (about 7.5º lat. N) by a freeze in 1884.

However, no cold damage was noted in South Florida following the low

temperatures of the winter of 1957-1958 which had severe effects on

many mango, avocado, lychee and lime trees. Dr. Henry Nehrling reported

that a tamarind tree in his garden at Gotha, Florida, though damaged by

freezes, always sprouted out again from the roots. In northwestern

India, the tree grows well but the fruits do not ripen. Dry weather is

important during the period of fruit development. In South Malaya,

where there are frequent rains at this time, the tamarind does not bear.

Soil

The tree tolerates a

great diversity of soil types, from deep alluvial soil to rocky land

and porous, oolitic limestone. It withstands salt spray and can be

planted fairly close to the seashore.

Propagation

Tamarind seeds

remain viable for months, will germinate in a week after planting. In

the past, propagation has been customarily by seed sown in position,

with thorny branches protecting the young seedlings. However, today,

young trees are usually grown in nurseries. And there is intensified

interest in vegetative propagation of selected varieties because of the

commercial potential of tamarind products. The tree can be grown easily

from cuttings, or by shield-budding, side-veneer grafting, or

air-layering.

Culture

Nursery-grown trees

are usually transplanted during the early rainy season. If kept until

the second rainy season, the plants must be cut back and the taproot

trimmed. Spacing may be 33 to 65 ft (10-20 m) between trees each way,

depending on the fertility of the soil. With sufficient water and

regular weeding, the seedlings will reach 2 ft (60 cm) the first year

and 4 ft (120 cm) by the second year.

In Madagascar, seedlings

have begun to bear in the 4th year; in Mexico, usually in the 5th year;

but in India, there may be a delay of 10 to 14 years before fruiting.

The tree bears abundantly up to an age of 50-60 years or sometimes

longer, then productivity declines, though it may live another 150

years.

Season

Mexican studies

reveal that the fruits begin to dehydrate 203 days after fruit-set,

losing approximately 1/2 moisture up to the stage of full ripeness,

about 245 days from fruit-set. In Florida, Central America, and the

West Indies, the flowers appear in summer, the green fruits are found

in December and January and ripening takes place from April through

June. In Hawaii the fruits ripen in late summer and fall.

Harvesting

Tamarinds may be

left on the tree for as long as 6 months after maturity so that the

moisture content will be reduced to 20% or lower. Fruits for immediate

processing are often harvested by pulling the pod away from the stalk

which is left with the long, longitudinal fibers attached. In India,

harvesters may merely shake the branches to cause mature fruits to fall

and they leave the remainder to fall naturally when ripe. Pickers are

not allowed to knock the fruits off with poles as this would damage

developing leaves and flowers. To keep the fruit intact for marketing

fresh, the stalks must be clipped from the branches so as not to damage

the shell.

Yield

A mature tree may

annually produce 330 to 500 lbs (150-225 kg) of fruits, of which the

pulp may constitute 30 to 55%, the shells and fiber, 11 to 30 %, and

the seeds, 33 to 40%.

Keeping Quality

To preserve

tamarinds for future use, they may be merely shelled, layered with

sugar in boxes or pressed into tight balls and covered with cloth and

kept in a cool, dry place. For shipment to processors, tamarinds may be

shelled, layered with sugar in barrels and covered with boiling sirup.

East Indians shell the fruits and sprinkle them lightly with salt as a

preservative. In Java, the salted pulp is rolled into balls, steamed

and sun-dried, then exposed to dew for a week before being packed in

stone jars. In India, the pulp, with or without seeds and fibers may be

mixed with salt (10%), pounded into blocks, wrapped in palmleaf

matting, and packed in burlap sacks for marketing. To store for long

periods, the blocks of pulp may be first steamed or sun-dried for

several days.

Pests and

Diseases

One of the major pests of the tamarind tree in India is the Oriental yellow scale, Aonidiella orientalis. Tamarind scale, A. tamarindi, and black, or olive scale, Saissetia oleae,

are also partial to tamarind but of less importance. Butani (1970)

lists 8 other scale species that may be found on the tree, the young

and adults sucking the sap of buds and flowers and accordingly reducing

the crop.

The mealybug, Planococcus lilacinus, is a leading pest of tamarind in India, causing leaf-fall and sometimes shedding of young fruits. Another mealybug, Nipaecoccus viridis, is less of a menace except in South India where it is common on many fruit trees and ornamental plants. Chionaspis acuminata-atricolor and Aspidiotus spp., suck the sap of twigs and branches and the latter also feeds on young fruits. White grubs of Holotrichia insularis may feed on the roots of young seedlings. The nematodes, Xiphinema citri and Longidorus elongatus may affect the roots of older trees. Other predators attacking the leaves or flowers include the caterpillars, Thosea aperiens, Thalarsodes quadraria, Stauropus alternus, and Laspeyresia palamedes; the black citrus aphid, Toxoptera aurantii, the whitefly, Acaudaleyrodes rachispora; thrips, Ramaswamia hiella subnudula, Scirtothrips dorsalis, and Haplothrips ceylonicus; and cow bugs, Oxyrhachis tarandus, Otinotus onerotus, and Laptoentrus obliquis.

Fruit borers include larvae of the cigarette beetle, Lasioderma serricorne, also of Virachola isocrates, Dichocrocis punctiferalis, Tribolium castaneum, Phycita orthoclina, Cryptophlebia (Argyroploca) illepide, Oecadarchis sp., Holocera pulverea, Assara albicostalis, Araecerus suturalis, Aephitobius laevigiatus, and Aphomia gularis. The latter infests ripening pods on the tree and persists in the stored fruits, as do the tamarind beetle, Pachymerus (Coryoborus) gonogra, and tamarind seed borer, Calandra (Sitophilus) linearis. The rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae, the rice moth, Corcyra cepholonica, and the fig moth, Ephestia cautella, infest the fruits in storage. The lesser grain borer, Rhyzopertha dominica bores into stored seeds.

In India, a bacterial leaf-spot may occur. Sooty mold is caused by Meliola tamarindi. Rots attacking the tree include saprot, Xylaria euglossa, brownish saprot, Polyporus calcuttensis, and white rot, Trametes floccosa. The separated pulp has good keeping quality but is subject to various molds in refrigerated storage.

Fig 32: Acid-sweet pulp of the tamarind (Tamarindus indica)

is blended with sugar as a confection, or preserved as jam

or nectar. It enhances chutney and some well-known sauces.

Fig. 33: Bahamian children hold mature but still green

tamarinds in hot ashes until they sizzle, then dip the

tip in the ashes and eat them. The high calcium

content contributes to good teeth.

Food Uses

The food uses of

the tamarind are many. The tender, immature, very sour pods are cooked

as seasoning with rice, fish and meats in India. The fully-grown, but

still unripe fruits, called "swells" in the Bahamas, are roasted in

coals until they burst and the skin is then peeled back and the

sizzling pulp dipped in wood ashes and eaten. The fully ripe, fresh

fruit is relished out-of-hand by children and adults, alike. The

dehydrated fruits are easily recognized when picking by their

comparatively light weight, hollow sound when tapped and the cracking

of the shell under gentle pressure. The shell lifts readily from the

pulp and the lengthwise fibers are removed by holding the stem with one

hand and slipping the pulp downward with the other. The pulp is made

into a variety of products. It is an important ingredient in chutneys,

curries and sauces, including some brands of Worcestershire and

barbecue sauce, and in a special Indian seafood pickle called "tamarind

fish". Sugared tamarind pulp is often prepared as a confection. For

this purpose, it is desirable to separate the pulp from the seeds

without using water. If ripe, fresh, undehydrated tamarinds are

available, this may be done by pressing the shelled and defibered

fruits through a colander while adding powdered sugar to the point

where the pulp no longer sticks to the fingers. The seeded pulp is then

shaped into balls and coated with powdered sugar. If the tamarinds are

dehydrated, it is less laborious to layer the shelled fruits with

granulated sugar in a stone crock and bake in a moderately warm oven

for about 4 hours until the sugar is melted, then the mass is rubbed

through a sieve, mixed with sugar to a stiff paste, and formed into

patties. This sweetmeat is commonly found on the market in Jamaica,

Cuba and the Dominican Republic. In Panama, the pulp may be sold in

corn husks, palmleaf fiber baskets, or in plastic bags.

Tamarind

ade has long been a popular drink in the Tropics and it is now bottled

in carbonated form in Guatemala, Mexico, Puerto Rico and elsewhere.

Formulas for the commercial production of spiced tamarind beverages

have been developed by technologists in India. The simplest home method

of preparing the ade is to shell the fruits, place 3 or 4 in a bottle

of water, let stand for a short time, add a tablespoonful of sugar and

shake vigorously. For a richer beverage, a quantity of shelled

tamarinds may be covered with a hot sugar sirup and allowed to stand

several days (with or without the addition of seasonings such as

cloves, cinnamon, allspice, ginger, pepper or lime slices) and finally

diluted as desired with ice water and strained.

In Brazil, a

quantity of shelled fruits may be covered with cold water and allowed

to stand 10 to 12 hours, the seeds are strained out, and a cup of sugar

is added for every 2 cups of pulp; the mixture is boiled for 15 to 20

minutes and then put up in glass jars topped with paraffin. In another

method, shelled tamarinds with an equal quantity of sugar may be

covered with water and boiled for a few minutes until stirring shows

that the pulp has loosened from the seeds, then pressed through a

sieve. The strained pulp, much like apple butter in appearance, can be

stored under refrigeration for use in cold drinks or as a sauce for

meats and poultry, plain cakes or puddings. A foamy "tamarind shake" is

made by stirring this sauce into an equal amount of dark-brown sugar

and then adding a tablespoonful of the mixture to 8 ounces of a plain

carbonated beverage and whipping it in an electric blender.

If

twice as much water as tamarinds is used in cooking, the strained

product will be a sirup rather than a sauce. Sometimes a little soda is

added. Tamarind sirup is bottled for domestic use and export in Puerto

Rico. In Mayaguez, street vendors sell cones of shaved ice saturated

with tamarind sirup. Tamarind pulp can be made into a tart jelly, and

tamarind jam is canned commercially in Costa Rica. Tamarind sherbet and

ice cream are popular and refreshing. In making fruit preserves,

tamarind is sometimes combined with guava, papaya or banana. Sometimes

the fruit is made into wine.

Inasmuch as shelling by hand is

laborious and requires 8 man-hours to produce 100 lbs (45 kg) of

shelled fruits, food technologists at the University of Puerto Rico

have developed a method of pulp extraction for industrial use. They

found that shelling by mechanical means alone is impossible because of

the high pectin and low moisture content of the pulp. Therefore,

inspected and washed pods are passed through a shell-breaking grater,

then fed into stainless steel tanks equipped with agitators. Water is

added at the ratio of 1:1 1/2 or 1:2 pulp/water, and the fruits are

agitated for 5 to 7 minutes. The resulting mash is then passed through

a screen while nylon brushes separate the shells and seeds. Next the

pulp is paddled through a finer screen, pasteurized, and canned.

Young

leaves and very young seedlings and flowers are cooked and eaten as

greens and in curries in India. In Zimbabwe, the leaves are added to

soup and the flowers are an ingredient in salads.

Tamarind seeds

have been used in a limited way as emergency food. They are roasted,

soaked to remove the seedcoat, then boiled or fried, or ground to a

flour or starch. Roasted seeds are ground and used as a substitute for,

or adulterant of, coffee. In Thailand they are sold for this purpose.

In the past, the great bulk of seeds available as a by-product of

processing tamarinds, has gone to waste. In 1942, two Indian

scientists, T. P. Ghose and S. Krishna, announced that the decorticated

kernels contained 46 to 48% of a gel-forming substance. Dr. G. R. Savur

of the Pectin Manufacturing Company, Bombay, patented a process for the

production of a purified product, called "Jellose", "polyose", or

"pectin", which has been found superior to fruit pectin in the

manufacture of jellies, jams, and marmalades. It can be used in fruit

preserving with or without acids and gelatinizes with sugar

concentrates even in cold water or milk. It is recommended as a

stabilizer in ice cream, mayonnaise and cheese and as an ingredient or

agent in a number of pharmaceutical products.

| Food

Value Per

100 g of Edible Portion* |

|

|

Pulp (ripe)* | Leaves (young) | Flowers |

| Calories |

115 | | |

| Moisture

|

28.2-52 g | 70.5 g | 80 g |

| Protein |

3.10 g | 5.8 g | 0.45 g |

| Fat |

0.1 g | 2.1 g | 1.54 g |

| Fiber |

5.6 g | 1.9 g | 1.5 g |

| Carbohydrates |

67.4 g | 18.2 g | |

| Invert Sugars |

30-41 g | | |

| 70% glucose; 30% fructose |

| | |

| Ash |

2.9 g | 1.5 g | 0.72 g |

| Calcium |

35-170 mg | 101 mg | 35.5 mg |

| Magnesium |

57

mg | 71 mg | |

| Phosphorus | 54-110 mg | 140 mg | 45.6 mg | | Iron | 1.3-10.9 mg | 5.2 mg | 1.5 mg | | Copper | | 2.09 mg | | | Chlorine | | 94 mg | | | Sulfur | | 63 mg | | | Sodium | 24 mg | | | | Potassium | 375 mg | | | | Vitamin A | 15 I.U. | 250 mcg | 0.31 mg | | Thiamine | 0.16 mg | 0.24 mg | 0.072 mg | | Riboflavin | 0.07 mg | 0.17 mg | 0.148 mg | | Niacin | 0.6-0.7 mg | 4.1 mg | 1.14 mg | | Ascorbic Acid | 0.7-3.0 mg | 3.0 mg | 13.8 mg | | Oxalic Acid | | 196 mg | | | Tartaric Acid | 8-23.8 mg | | | | Oxalic Acid | trace only | | |

|

*The pulp is considered a promising source of tartaric acid,

alcohol (12% yield) and pectin (2 1/2% yield). The red pulp of some

types contains the pigment, chrysanthemin.

Seeds contain approximately 63% starch, 14-18% albuminoids, and 4.5-6.5% of a semi-drying oil.

Food Value

Analyses of the

pulp are many and varied. Roughly, they show the pulp to be rich in

calcium, phosphorus, iron, thiamine and riboflavin and a good source of

niacin. Ascorbic acid content is low except in the peel of young green

fruits.

Other Uses

Fruit pulp:

in West Africa, an infusion of the whole pods is added to the dye when

coloring goat hides. The fruit pulp may be used as a fixative with

turmeric or annatto in dyeing and has served to coagulate rubber latex.

The pulp, mixed with sea water, cleans silver, copper and brass.

Leaves:

The leaves are eaten by cattle and goats, and furnish fodder for

silkworms–Anaphe sp. in India, Hypsoides vuilletii in West Africa. The

fine silk is considered superior for embroidery.

Tamarind leaves and

flowers are useful as mordants in dyeing. A yellow dye derived from the

leaves colors wool red and turns indigo-dyed silk to green. Tamarind

leaves in boiling water are employed to bleach the leaves of the buri

palm (Corypha elata Roxb.) to prepare them for hat-making. The foliage

is a common mulch for tobacco plantings.

Flowers:

The flowers are rated as a good source of nectar for honeybees in South

India. The honey is golden-yellow and slightly acid in flavor.

Seeds:

The powder made from tamarind kernels has been adopted by the Indian

textile industry as 300% more efficient and more economical than

cornstarch for sizing and finishing cotton, jute and spun viscose, as

well as having other technical advantages. It is commonly used for

dressing homemade blankets. Other industrial uses include employment in

color printing of textiles, paper sizing, leather treating, the

manufacture of a structural plastic, a glue for wood, a stabilizer in

bricks, a binder in sawdust briquettes, and a thickener in some

explosives. It is exported to Japan, the United States, Canada and the

United Kingdom.

Tamarind seeds yield an amber oil useful as an

illuminant and as a varnish especially preferred for painting dolls and

idols. The oil is said to be palatable and of culinary quality. The

tannin-rich seedcoat (testa) is under investigation as having some

utility as an adhesive for plywoods and in dyeing and tanning, though

it is of inferior quality and gives a red hue to leather.

Wood: The sapwood of the

tamarind tree is pale-yellow. The heartwood is rather small, dark

purplish-brown, very hard, heavy, strong, durable and insect-resistant.

It bends well and takes a good polish and, while hard to work, it is

highly prized for furniture, panelling, wheels, axles, gears for mills,

ploughs, planking for sides of boats, wells, mallets, knife and tool

handles, rice pounders, mortars and pestles. It has at times been sold

as "Madeira mahogany". Wide boards are rare, despite the trunk

dimensions of old trees, since they tend to become hollow-centered. The

wood is valued for fuel, especially for brick kilns, for it gives off

an intense heat, and it also yields a charcoal for the manufacture of

gun-powder. In Malaysia, even though the trees are seldom felled, they

are frequently topped to obtain firewood. The wood ashes are employed

in tanning and in de-hairing goatskins. Young stems and also slender

roots of the tamarind tree are fashioned into walking-sticks.

Twigs and barks:

Tamarind twigs are sometimes used as "chewsticks" and the bark of the

tree as a masticatory, alone or in place of lime with betelnut. The

bark contains up to 7% tannin and is often employed in tanning hides

and in dyeing, and is burned to make an ink. Bark from young trees

yields a low-quality fiber used for twine and string. Galls on the

young branches are used in tanning.

Lac:

The tamarind tree is a host for the lac insect, Kerria lacca, that

deposits a resin on the twigs. The lac may be harvested and sold as

stick-lac for the production of lacquers and varnish. If it is not seen

as a useful byproduct, tamarind growers trim off the resinous twigs and

discard them.

Medicinal

Uses:

Medicinal uses of the tamarind are uncountable. The pulp has been

official in the British and American and most other pharmacopoeias and

some 200,000 lbs (90,000 kg) of the shelled fruits have been annually

imported into the United States for the drug trade, primarily from the

Lesser Antilles and Mexico. The European supply has come largely from

Calcutta, Egypt and the Greater Antilles. Tamarind preparations are

universally recognized as refrigerants in fevers and as laxatives and

carminatives. Alone, or in combination with lime juice, honey, milk,

dates, spices or camphor, the pulp is considered effective as a

digestive, even for elephants, and as a remedy for biliousness and bile

disorders, and as an antiscorbutic. In native practice, the pulp is

applied on inflammations, is used in a gargle for sore throat and,

mixed with salt, as a liniment for rheumatism. It is, further,

administered to alleviate sunstroke, Datura poisoning, and alcoholic

intoxication. In Southeast Asia, the fruit is prescribed to counteract

the ill effects of overdoses of false chaulmoogra, Hydnocarpus

anthelmintica Pierre, given in leprosy. The pulp is said to aid the

restoration of sensation in cases of paralysis. In Colombia, an

ointment made of tamarind pulp, butter, and other ingredients is used

to rid domestic animals of vermin.

Tamarind leaves and flowers,

dried or boiled, are used as poultices for swollen joints, sprains and

boils. Lotions and extracts made from them are used in treating

conjunctivitis, as antiseptics, as vermifuges, treatments for

dysentery, jaundice, erysipelas and hemorrhoids and various other

ailments. The fruit shells are burned and reduced to an alkaline ash

which enters into medicinal formulas. The bark of the tree is regarded

as an effective astringent, tonic and febrifuge. Fried with salt and

pulverized to an ash, it is given as a remedy for indigestion and

colic. A decoction is used in cases of gingivitis and asthma and eye

inflammations; and lotions and poultices made from the bark are applied

on open sores and caterpillar rashes. The powdered seeds are made into

a paste for drawing boils and, with or without cumin seeds and palm

sugar, are prescribed for chronic diarrhea and dysentery. The seedcoat,

too, is astringent, and it, also, is specified for the latter

disorders. An infusion of the roots is believed to have curative value

in chest complaints and is an ingredient in prescriptions for leprosy.

The

leaves and roots contain the glycosides: vitexin, isovitexin, orientin

and isoorientin. The bark yields the alkaloid, hordenine.

Superstitions

Few plants

will survive beneath a tamarind tree and there is a superstition that

it is harmful to sleep or to tie a horse beneath one, probably because

of the corrosive effect that fallen leaves have on fabrics in damp

weather. Some African tribes venerate the tamarind tree as sacred. To

certain Burmese, the tree represents the dwelling-place of the rain god

and some hold the belief that the tree raises the temperature in its

immediate vicinity. Hindus may marry a tamarind tree to a mango tree

before eating the fruits of the latter. In Nyasaland, tamarind bark

soaked with corn is given to domestic fowl in the belief that, if they

stray or are stolen, it will cause them to return home. In Malaya, a

little tamarind and coconut milk is placed in the mouth of an infant at

birth, and the bark and fruit are given to elephants to make them wise.

|

|