Vanilla Growing in Uganda

Scientific Name: Vanilla planifolia

Family: Orchidaceae

Whilst working in Uganda for the Uganda Development

Corporation, one of my tasks was to develop a 24-hectare block of

Vanilla. This is a semi-terrestrial orchid, Vanilla fragrans syn. V. planifolia,

a member of the ORCHIDACEAE family. The sticks of vanilla you buy in

the shop are the pods, which have to be cured after harvesting.

The

object of developing the block was to get experience in growing vanilla

on a large scale, and eventually to provide planting material for local

African growers as another source of export income besides Robusta

coffee. Hopefully, the plantation has survived the political upheavals

of the past 20 years.

Management of the plantation involved a

three-year rotation, i.e. crop for two years and rest for one, thus the

area was split up into three eight-hectare sections.

Top Shade

Vanilla requires top shade. This was provided by Maesopsis eminii (RHAMNACEAE

family) trees, known locally as "Musizi". These are tall, fast-growing

African trees with straight lobes and a spreading canopy of small

leaves which cast a light dappled shade, ideal for vanilla. These were

raised in soil blocks and planted out 6m apart each way. They grew more

than a metre in six months. The correct amount of shade is important.

We found Vanilla is susceptible to too much shade, which tends to

weaken the vines.

Support Trees

To support the vanilla vines, we grew Jatropha curcas

(EUPHORBIACEAE) or Physic nut trees. The Vanilla roots attach

themselves to the rough bark of these trees and draw nourishment from

the organic matter and moisture in the bark. A vine in the fruit

section of the Cairns Flecker Botanic Gardens can be seen with its

roots attached to a palm tree. The Physic nut is a low-growing tree and

easy to keep in check by slashing unwanted growth to regulate the

shade. Thus the Vanilla vines had permanent living supports instead of

white ant-susceptible posts, each tree supporting two vines, one on

either side but not looped over into adjacent trees. These support

trees were planted at 3m x 1m spacings.

We did also consider

trying Casuarina as support trees without top shade, but the growth of

the species we had was extremely vigorous in that climate and we feared

that the trees might produce too much shade and become difficult to

manage in time. The "Musizi" and Physic nut combination proved easy to

manage.

Planting

Six-node cuttings are taken of mature

vegetative wood - not from wood which has flowered. Two cuttings, one

on either side, are planted up against the support trees with the

bottom two nodes under the mulch - not in the soil, otherwise they tend

to rot. If necessary, they can be tied with string to the support

trees. Use a string which will rot, not plastic twine.

In the

part of the country where we grew Vanilla and Cocoa, known as the

'fertile crescent' around the top end of Lake Victoria (Lake Amin) it

rained just about every week. But under our conditions with our long

dry periods, we would need overhead sprinkler irrigation. After

planting, there is about a three-year immaturity period.

Slashing and Mulching

Only

slashing of the grass was carried out between the rows and the trash

piled up against the bases of the vines. Vanilla roots, after having

descended the support trees then travel along the surface of the ground

beneath the mulch and across the rows under the mat of grass. Where

trash was lacking we trucked in bagasse from local sugar mills.

In

Uganda, cheap hand labour did the slashing and mulching, but under our

conditions lightweight slashing equipment would be needed so as not to

damage surface roots. Something like a four-wheel bike with wide

flotation tyres pulling a separately powered or P.T.0.-powered

twin-bladed slasher to throw the trash under the rows in one pass.

Mulching must be thick enough to, hopefully, control all weeds - so

forget Roundup®!

Pruning

Shoots from the cutting eventually

grow up through the support trees and become pendulous. Flowers form

later from the axils of most leaves. The soft tips were removed near

ground level. These were taken to the nursery and rooted under shade in

bags filled with fern fibre to supply the out-growers.

After the

beans were harvested, the stem which has borne the pods is cut back to

a growth bud near the support tree and where there are plenty of aerial

roots.

Vines were always pruned and pollinated according to

their vigour. No weaklings were allowed to bear fruit. Only vigorous,

healthy vines were brought into bearing, leaving only the amount of

mature fruit wood that the vine is able to support. When pruning, one

must always think one year to 18 months ahead, at least under Uganda

conditions. That is for the growth to form, flower set and mature its

pods.

Pollination

In Uganda, flowering occurred in March-June

and September-October. There were no suitable pollinating insects or

birds so this job was done by hand, one being employed almost full-time

and with excellent results. Using a pointed stick, he transferred the

pollen masses onto the surface of the stigma in each flower. 5-10

flowers per raceme are pollinated according to the vigour of the vine.

After pollination, the pods took about six months to form.

Curing

The

pods are ready for picking when the ends become slightly yellow. After

picking, the pods were dipped in hot water at 65 °C for two minutes.

After draining, the pods were laid in lines on a cotton (not wool)

blanket. We experimented and found a cotton blanket was best. The

blanket is then folded over the pods and then rolled up. The rolls of

blankets were placed on shelves in a dry, airy shed to allow the pods

to sweat. The blankets were unrolled each day to expose the pods to the

sun for a period of around half an hour. This was repeated until curing

was finished. The whole idea is to retain the juices in the pods and

not to desiccate them. Once cured, crystals of vanillin form on the

outside of the pods which give off a pleasant vanilla odour.

After storage for a couple of months, the cured pods were packed in tin boxes lined with silver paper and sealed for export.

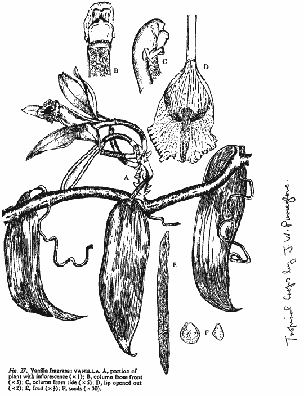

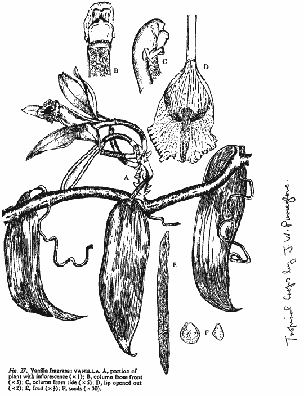

Fig. 1

Pests and Diseases

Nothing significant in Uganda. Minor problems such as snails were controlled with baits and ants with insecticide.

Economics

I

can't remember the yield per hectare or the price we received in those

days, but it was certainly profitable under our conditions with our

cheap labour! According to H. F. Macmillan's Tropical Planting and

Gardening 1991 edition, demand for Vanilla rose 10-15 years ago, the

price rising from US$15 per kg to $120 per kg. The book quotes Vanilla

as being one of the world's most profitable Agricultural Commodities.

About

18 months ago, I noticed that Vanilla was quoted at $48 per kg under

market prices in the press. Macmillan's quotes yields of from 500-800

kg cured pods per hectare per year over a crop life of about seven

years.

Taking the lower figure of 500 kg per hectare, and say $50 per kg, we have a gross figure of $25,000 per hectare. Not bad!

Using

current technology, we should be able to improve both the yield and

quality. Under our weather conditions, as well as irrigation,

windbreaks would also be necessary. Based on my practical experience, I

do not think it is sufficient just to plant vanilla in the rainforest

and let it look after itself because of excessive shade. Too much shade

I found was very detrimental to Vanilla.

Anyway, if you want to have a go at growing Vanilla, I wish you the best of luck.

Back to

Vanilla Page

|