From the Manual Of

Tropical And Subtropical Fruits

by Wilson Popenoe

The Mango

Races And

Varieties

The classification of mangos must be considered from two distinct

standpoints. First, there are numerous seedling races; and second,

there are horticultural groups of varieties propagated by grafting or

budding.

The seedling races have not been studied in all parts

of the tropics. Most of those in America are now fairly well known, but

they are probably few compared to those of the Asiatic tropics. The

latter region has not been explored thoroughly.

So far as known,

all the seedling races are polyembryonic. Individuals reproduce the

racial characteristics with remarkable constancy. Numerous writers have

said that these races (incorrectly termed varieties) come true from

seed, and that there is no need of grafting or budding. There is enough

variation among the seedlings, however, to make some of them more

desirable than others. When one has been propagated by budding or

grafting it becomes a true horticultural variety.

The

classification of mangos has been discussed by Burns and Prayag in the

Agricultural Journal of India (1915); by P. H. Rolfs in Bulletin 127,

Florida Agricultural Experiment Station; and by the author in the

Proceedings of the American Pomological Society for 1915 and 1917.

The

abundance of grafted mangos has led Indian investigators to neglect the

seedling races. Doubtless some of the horticultural groups of grafted

varieties represent seedling races. C. Maries, in the Dictionary of the

Economic Products of India, grouped the named varieties with which he

was familiar in five "cultivated races." Probably some of these

represent seedling races. The antiquity of its culture in India and the

extensive employment of vegetative means of propagation have placed the

mango on a different footing from that which it occupies in regions

where it has been grown relatively a short time and propagated

principally by seed. In India, the horticultural varieties are most

prominent; elsewhere, seedling races are more in evidence.

The mangos of

the Malayan Archipelago have been less thoroughly studied, from a

pomological standpoint, than those of any other region. The botanist

Blume (Museum Botanicum Lugduno-Batavum) viewed them botanically, and

described as botanical varieties a number of forms which are in all

probability analogous to the seedling races of other regions. In

addition to races, there are a number of distinct species of Mangifera

in the Malayan region which bear fruits closely resembling true mangos.

These must be studied in connection with any attempt to straighten out

the classification of horticultural or pomological forms.

CochinChina

appears to be the home of a race of mangos which is unusual in

character, and which is certainly one of the most valuable of all. This

is the Cambodiana. By some botanists it is considered a distinct

species of Mangifera. It seems to be identical with the race grown in

the Philippine Islands. The latter has been carried to tropical

America, where it is known as Manila (Mexico) and Filipino (Cuba).

David Fairchild, who studied this race in Saigon, CochinChina, and

introduced it into the United States, describes it as a mango of medium

size, yellow when ripe, furnished with a short beak, and having a faint

but agreeable odor. The flesh varies from light to deep orange in

color, and is never fibrous. The flavor is not so rich as that of the

Alphonse, but is nevertheless delicious. One of the plants grown from

the seed sent to the United States by Fairchild has given rise to the

horticultural variety Cambodiana, now propagated vegetatively in

Florida.

There appear to be several different forms of this

race. Three forms are grown in the Philippines, where they are

distinguished by separate names. P. J. Wester states:

"There are

three very distinct types of mangos in the Philippines: the Carabao,

the Pico (also known as Padero), and the Pahutan, in some districts

called Supsupen and Chupadero. The Carabao is the mango most esteemed

and most generally planted." He further says, "Although uniform as

types, there is considerable variation in the form and size of the

fruit and presence of fiber and size of seed in both the Carabao and

Pico mangos, and careful selection will not only bring to light

varieties much larger than the average fruit of these types, but also

those having a much smaller percentage of fiber and seed than the

average fruit."

The seedling mangos of the Hawaiian Islands have

been given some attention by Higgins. In Bulletin 12 of the Hawaii

Agricultural Experiment Station he describes a number of them. Judging

from his illustration, the Hawaiian Sweet mango is the common seedling

race of the West Indies.

The French island of Reunion is said to

be the source of several seedling races which have been introduced into

tropical America. Paul Hubert1 says the mango

has become

thoroughly naturalized in this island. He mentions thirteen varieties

which are the most common; the names of several are the same as those

of well-known varieties in the French West Indies.

1 Fruits

des Pays Chauds.

Little is known of the mangos cultivated on the African coast and in

Madagascar.

The

seedling races of Cuba and those of Florida are practically the same,

seeds having carried from the former region to the latter. The

principal race is the one known in Cuba as mango (in contradistinction

to manga, the race second in importance), and in Florida as No. 11.

This is the common race of Mexico and many other parts of tropical

America. For convenience it may be termed the West Indian. The tree is

erect, 60 to 70 feet in height, with an open crown. The panicle is 8 to

12 inches long, with the axis reddish maroon in color. The fruit is

strongly compressed laterally, with curved and beaked apex. It is

yellow in color, often blushed with crimson; the fiber is long and

coarse, and the quality of the fruit poor, although the flavor is very

sweet.

The manga race of Cuba is less widely grown in other

regions, although it is well represented in Florida. The tree is

spreading, 35 to 40 feet high, with a dense round-topped crown. The

panicle is 6 to 10 inches long, stout, pale green in color, often

tinged with red. The fruit is plump, not beaked, yellow in color, with

long, fine fibers through the flesh. Two forms of this race are common,

manga amarilla and manga blanca. The former, known in Florida as

turpentine or peach mango, has an elongated fruit, deep orange yellow

in color, with bright orange flesh. The latter, known in Florida as

apple or Bombay mango, has a roundish oblique fruit, bright yellow in

color with whitish yellow flesh.

The Filipino (Philippine) race

probably reached Cuba from Mexico, and thence was carried to Florida.

It is the most delicious and highly esteemed of seedling mangos in all

of these regions. Indeed, it ranks in quality with many of the choice

grafted varieties from India. The tree is erect, 30 to 35 feet high,

with a dense oval crown. The panicle is 12 to 24 inches long, pale

green, sometimes tinged with red. The fruit is strongly compressed

laterally, sharply pointed rather than curved or beaked at the apex,

lemon-yellow in color, with deep yellow flesh almost free from fiber.

In Florida there are comparatively few trees of this race.

In

addition to the above, there are several other races of limited

distribution in Cuba. The biscochuelo mango of Santiago de Cuba is an

excellent fruit, worthy of propagation in other regions. The mango

Chino of the Quinta Aviles at Cienfuegos (a remarkable mango orchard

established years ago) is a large fruit always in great demand in

Habana markets. It is not, however, of rich flavor or fine quality.

Manga mamey, also of the Quinta Aviles at Cienfuegos is of better

quality than mango Chino, but is not so well known in Habana.

In

Jamaica the No. 11 race is esteemed above most other seedlings. It had

its origin in one of the grafted trees found on a captured French

vessel and brought to the island in 1782, as related on a foregoing

page.

The seedling races of Porto Rico have been treated in detail by G. N.

Collins1

and more recently by C. F. Kinman. The most prolific and popular race

is known as mango bianco. The mangotina is found near Ponce; it is

rather inferior in quality. The redondo is a seven-ounce fruit, lacking

in richness. The largo has a small oval fruit with much fiber. The name

pina is applied to several distinct forms, the commonest being a long

fruit of inferior quality. None of these Porto Rican forms seems to

merit propagation.

In Mexico the principal races are the common

West Indian, and the Manila or Filipino. The latter is grown

principally in the state of Vera Cruz. Its culture should be extended

to other parts of the country, as well as to other tropical countries

where it is not now grown.

1 Bull.

28, U. S. Dept. Agr.

There

is one race in Brazil which is of exceptional value. This is the manga

da rosa (rose mango), grown commercially in the vicinity of Pernambuco

and to a less extent at Bahia and Rio de Janeiro. While frequently

propagated by grafting, it is polyembryonic and should come true to

race when grown from seed. It is heart-shaped, slightly beaked; and of

good size. Its coloring is unusually beautiful. The fiber is coarse and

rather long, but not so troublesome as in many seedling races. The

flavor is rich and pleasant. This mango is believed to have been

brought to Brazil from Mauritius. The espada race of Brazil is of

little value : its fruit is slender, curved at both ends, green in

color, and of poor quality.

The horticultural varieties of the

mango are numerous. C. Maries reported having collected nearly 500, of

which 100 were good. Many of these were, however, of limited

distribution and little importance. More recent Indian writers catalog

from 100 to 200 varieties. The author has published in the Pomona

College Journal of Economic Botany (December, 1911) a descriptive list

of about 300, which includes the best-known from all parts of the

world. Some of these, however, are probably seedling races, not

horticultural varieties propagated by grafting or budding. Many writers

have made no distinction between races, in which the seedlings

reproduce the characteristics of the parent, and varieties, which can

be propagated only by vegetative means.

The confusion which

involves mango nomenclature in India is rather appalling. There can be

no doubt that in numerous cases the same name is applied to several

distinct varieties, and it is equally certain that one variety in some

instances has several different names. In addition, some of the kinds

catalogued by Indian nurserymen probably never existed outside of their

own imaginations. There are only a few varieties which are well known

and highly esteemed in India. Most of these have been introduced into

the mango-growing regions of the Western Hemisphere by the Office of

Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction of the United States Department of

Agriculture. The varieties described in the following pages are the

best which have been tested in Florida up to the present. Most of them

are well-known Indian sorts. They are few in number, but it is not

possible to include in such a work as this a fully complete list. The

classification here made into groups based on natural resemblances

throws related varieties together and should aid the prospective

planter to gain an idea of the more salient characteristics of each.

Only the most important varieties in each group are described.

Mango Mulgoba

Group

In

this group the tree is usually erect, with a broad, dense crown. The

leaves are slender, smaller (especially in the variety Mulgoba) than in

some of the other groups, the primary transverse veins 22 to 24 pairs,

moderately conspicuous. The panicle is usually slender, frequently

drooping, 12 to 18 inches in length, the axis and laterals varying from

pale green tinged pink to rose pink, the pubescence heavier than in

most other groups. The flowers are usually very abundant on the

panicle. The staminodes are strongly developed, often capitate, one or

two sometimes fertile. In general, varieties of this group require the

stimulus of dry weather to make them flower profusely, and they show a

decided tendency to drop most of their fruits. Haden, however, holds

its fruits well. The fruit is usually oval. It varies in color from

dull green to yellow blushed red, and lacks a distinct beak. The flesh

is deep yellow to orange-yellow, variable in quality. The seed is

normally monoembryonic.

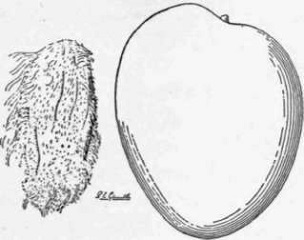

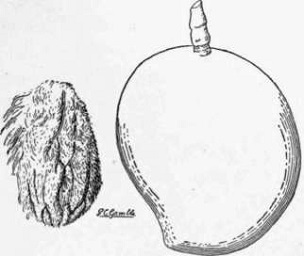

Mulgoba (Fig. 15). - Form oblong ovate

to ovate, laterally compressed; size medium to above medium, weight 9

1/2 to 14 1/2 ounces, length 3 1/2 to 4 1/2 inches, breadth 3 to 3 1/2

inches, base flattened, with the stem inserted obliquely in a very

shallow cavity; apex rounded to broadly pointed, the nak a small point

on the ventral surface about 1/2 inch above the longitudinal apex;

surface slightly undulating, deep to apricot-yellow in color, sometimes

overspread with scarlet around base and on exposed side, dots few to

numerous, small, lighter in color than surface; skin thick, tough,

tenacious, flesh bright orange-yellow, smooth and fine in texture, with

a pronounced and very agreeable aroma, very juicy, free from fiber, and

of rich piquant flavor; quality excellent; seed oblong to

oblong-reniform, plump, with sparse, stiff, short fibers 1/2 inch long

over the surface. Season in Florida July to September.

Introduced

into the United States in 1889 from Poona, India, by the United States

Department of Agriculture. This was the first grafted Indian variety to

fruit in the United States. In attractive coloring, delicate aromatic

flavor, and freedom from fiber, Mulgoba is scarcely excelled, but it

has proved irregular in its fruiting habits and for this reason cannot

be recommended for commercial planting expect in regions with dry

climates. The tree does not come into bearing at an early age. The name

Mulgoba (properly Malghoba) is taken from that of a native Indian dish,

and means "makes the mouth water."

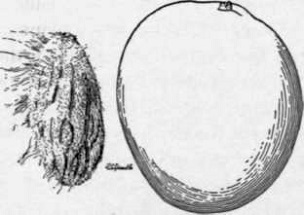

Haden (Fig. 16). - Form oval

to ovate, plump; size large to very large, weight 15 to 20 ounces,

sometimes up to 24 ounces, length 4 to 5 1/2 inches, breadth 3 1/2 to 4

1/2 inches, base rounded, the stem inserted almost squarely without

depression; apex rounded to broadly pointed, the nak depressed, 3/4

inch above the longitudinal apex; surface smooth, light to deep

apricot-yellow in color, overspread with crimson-scarlet, dots

numerous, large whitish yellow in color, skin very thick and tough;

flesh yellowish orange in color, firm, very juicy, fibrous only close

to the seed, and of sweet, rich, moderately piquant flavor; quality

good; seed oblong, plump, with considerable fiber along the ventral

edge and a few short stiff bristles elsewhere. Season in Florida July

and August. Originated at Coconut Grove, Florida, as a seedling of

Mulgoba. First propagated in 1910. The fruit is not so fine as that of

Mulgoba, but the tree is a stronger grower, comes into fruit at an

early age, and bears more regularly.

Fig. 15. The Mulgoba mango. (X 2/5)

Fig. 16. The Haden mango. (X 1/3)

Mango. Alphonse

Group

The

trees of this group are usually broad and spreading in habit, but in a

few cases, e.g., Amini, they may be rather tall, with an oval crown.

The foliage is abundant, bright to deep green in color, the leaves

medium to large in size, with primary transverse veins 20 to 24 pairs,

fairly conspicuous. The panicle is large, very broad toward the base,

stiff, sometimes stout, 10 to 18 inches long, the axis and laterals

pale green to dull rose-pink in color, glabrate to very finely and

sparsely pubescent. The flowers are not crowded on the panicle. The

staminodes are poorly developed, rarely capitate. Most varieties of

this group are not heavy bearers. Flowers are often produced sparingly,

or on only one side of the tree, but a much higher percentage of

flowers develops into fruits than in the Mulgoba group. Under average

conditions, most of the varieties bear small to fair crops. The fruit

is longer than broad, usually oblique at the base, and lacks a beak.

The stigmatic point or nak often forms a prominence on the ventral

surface above the apex. The color varies from yellowish green to bright

yellow blushed scarlet. The flesh is orange colored, free from fiber,

and is characterized by rich luscious flavor, in some varieties nearly

as good as that of Mulgoba. On an average, the quality of fruit is

better than in any other group. The seed contains but one embryo.

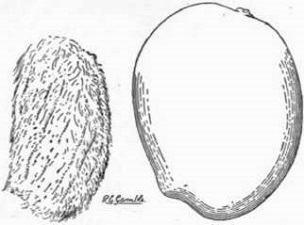

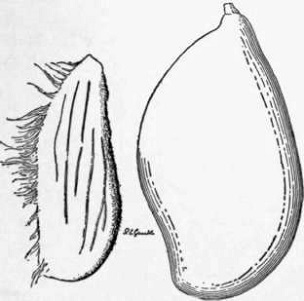

Amini

(Fig. 17). - Form oval, laterally compressed; size small to below

medium, weight 6 to 8 ounces, length 3 to 3 1/4 inches, breadth 2 1/2

to 2 3/4 inches, base obliquely flattened, cavity none; apex rounded,

the nak conspicuous and 5/16 inch above the end of the fruit; surface

smooth, deep yellow in color overspread with dull scarlet particularly

around the base, dots numerous, small, pale yellow; skin thick and

firm; flesh bright orange-yellow in color, melting, very juicy,

strongly aromatic, free from fiber, and of sweet unusually spicy

flavor; quality excellent; seed oblong-oval, very thin, with only a few

short fibers on the ventral edge. Season in Florida June and July.

Introduced

into the United States in 1901 by the United States Department of

Agriculture (S. P. I. No. 7104) from Bangalore, India. One of the most

satisfactory Indian varieties tested in Florida and the West Indies. It

is more regular in bearing than many others, and the aroma and flavor

of the fruit are excellent. Not to be confused with Amiri, which has

sometimes been sold under the name Long Amini. Amin (Sanskrit) means a

tall, pyramidal mango tree; amin (Arabic) means constant, faithful.

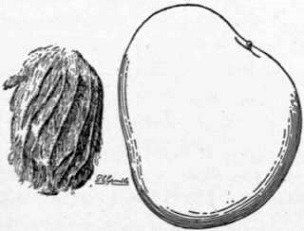

Bennett (Fig. 18). - Form ovate-oblique to ovate-cordate, very plump;

size below medium to medium, weight 7 to 12 ounces, length 3 to 3 1/4

inches, breadth 2 3/4 to 3 3/4 inches, base obliquely flattened, cavity

almost none; apex broadly pointed, the nak level or slightly depressed,

about 3/4 inch above end of fruit; surface smooth, yellow-green to

yellow-orange, dots few, light yellow; skin thick and tough, not easily

broken; flesh deep orange, free from fiber, firm and meaty, moderately

juicy, of pleasant aroma and sweet, rich, piquant flavor; quality

excellent; seed oblong-reniform, thick, with short stiff fibers over

the entire surface. Season in south Florida late July and August.

Introduced into the United States in 1902 by the United States

Department of Agriculture (S. P. I. 8419 and 8727) from Goregon, near

Bombay, India. Syn. Douglas Bennett's Alphonse. This is one of the

esteemed Alphonse mangos of western India. Some of the fruits produced

in Florida have been characterized by hard sour lumps in the flesh,

hence the variety has not made such a favorable impression as would

otherwise have been the case. The tree is vigorous, and bears more

regularly than Mulgoba. The Alphonse mangos are supposed to have been

named for Affonso (Alphonse) d'Albuquerque, one of the early governors

of the Portuguese possessions in India. The name has been corrupted to

Apoos, Afoos, Hafu.

Fig. 17. Amini mango. (X about 1/2)

Fig. 18. The Bennett mango. (X 2/5)

Pairi

(Fig. 19). - Form ovate-reniform to ovate-oblique, prominently beaked;

size below medium to medium, weight 7 to 10 ounces, length 3 to 3 1/2

inches, breadth 2 7/8 to 3 1/4 inches; base obliquely flattened,

cavity none; apex rounded to broadly pointed, with a conspicuous beak

slightly above it on the ventral side of the fruit; surface smooth to

undulating, yellow-green in color, suffused scarlet around the base,

the dots few, small, whitish yellow; skin moderately thick; flesh

bright yellow-orange in color, firm but juicy, of fine texture, free

from fiber, of pronounced and pleasant aroma and sweet, rich, spicy

flavor; quality excellent; seed thick, with short bristly fibers over

the entire surface. Season in south Florida July and August. Introduced

into the United States in 1902 from Bombay, India, by the United States

Department of Agriculture (S. P. I. 8730); a variety (S. P. I. 29510)

introduced under the same name in 1911 from Poona, India, has proved to

be slightly different. Syns. Paheri, Pirie, Pyrie. Ranks second only to

Alphonse in the markets of Bombay, India. William Burns says,

"Personally I prefer the slightly acid Pairi to the heavier and more

luscious Alphonse." Two subvarieties are known in India, Moti Pairi and

Kagdi Pairi. The tree is a good grower, and resembles Bennett in

productiveness, although it sometimes fruits more heavily. The word

Pairi is probably a corruption of the Portuguese proper name Pereira.

Rajpuri.

- Form roundish ovate to ovate-reniform, beaked; size below medium to

medium, weight 8 to 12 ounces, length 3 1/4 to 3 3/4 inches, breadth 3

to 3 1/2 inches; base flattened, scarcely oblique, cavity none; apex

bluntly pointed, with the prominent nak to one side; surface smooth,

green-yellow to yellow in color, over-spread with scarlet on exposed

side and around base; dots small, numerous, whitish; skin moderately

thick; flesh deep yellow in color, free from fiber, juicy, with

pronounced aroma and rich piquant flavor; quality excellent; seed

oblong-elliptic, thick, with short stiff fibers over the surface.

Season July and August in Florida.

Introduced

into the United States in 1901 from Bangalore, India, by the United

States Department of Agriculture (S. P. I. 7105). Syns. Rajpury,

Rajapuri, Rajabury, and Rajapurri. A fruit of fine quality, with aroma

and flavor distinct from that of other mangos. Its fruiting habits have

proved fairly good. Rajpur, name of a town in India (perhaps Rajapur?).

Fig. 19. The Pairi mango. (X 2/5)

Mango. Sandersha

Group

The tree is erect, stiff, with the crown less broad than in the

Mulgoba group and usually not so umbrageous. The foliage is fairly

abundant, deep green in color, the leaves comparatively small but

broad, with primary transverse veins 18 to 24 pairs, moderately

conspicuous. The panicle is small to large, broad toward the base, 8 to

18 inches long, stiff, the axis and laterals deep magenta-pink to

bright maroon, the pubescence very minute and inconspicuous. The

flowers are abundant but not closely crowded on the panicle. The

staminodes are weakly developed, rarely capitate or fertile. Varieties

of this group often flower in unfavorable weather, and they remain in

bloom during a long period. On the whole, the group is characterized by

a higher degree of productiveness than any other class of Indian mangos

yet grown in the United States. The fruit is long, usually tapering to

both base and apex and terminating in a prominent beak at the apex,

large in size, deep yellow in color, the flesh orange-yellow, and free

from fiber. The somewhat acid flavor makes the mangos of this group

more valuable as culinary than as dessert fruits. The seed is long,

containing normally one embryo, the cotyledons often not filling the

endocarp completely.

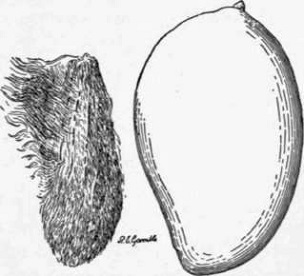

Sandersha (Fig. 20). - Form oblong,

tapering toward stem and prominently beaked at the apex; size large to

extremely large, weight 18 to 32 ounces, length 6 1/2 to 8 inches,

breadth 3 3/4 to 4 1/4 inches; base slender, extended; apex broadly

pointed, with the nak forming a prominent beak to the ventral side;

surface smooth, yellow to golden yellow in color, sometimes blushed

scarlet on exposed side, dots numerous, small, yellow-gray; flesh

orange-yellow in color, meaty, moderately juicy, free from fiber, and

of subacid, slightly aromatic flavor; dessert quality fair, culinary

quality excellent; seed long, slender, slightly curved, with fiber only

along the ventral edge. Season in south Florida August and September.

Introduced

into the United States in 1901 from Bangalore, India, by the United

States Department of Agriculture (S. P. I. 7108). Syns. Soondershaw,

Sandershaw, Sundersha. A variety introduced from Saharanpur, India,

under the name Sundershah (S. P. I. 10665) is probably distinct. The

tree has remarkably good fruiting habits. Etymology of name unknown.

Totapari.

- Form oval to ob-long-reniform, beaked; size medium, weight 10 to 12

ounces, length 4 1/5 to 5 inches, breadth 3 to 3 1/2 inches; base

rounded, the stem inserted squarely; apex broadly pointed, with the nak

forming a prominent beak to the ventral side; surface smooth, greenish

yellow in color, overspread with scarlet on exposed side; skin

moderately thick and tough; flesh bright yellow in color, unusually

juicy, free from fiber, moderately aromatic, and of subacid, moderately

rich flavor; dessert quality fair, culinary quality good; seed oblong,

rather thin, with small amount of fiber on edges. Season in south

Florida August and September.

Introduced into the United States

in 1902 from Bombay, India, by the United States Department of

Agriculture (S. P. I. 8732). Syn. Totafari. The tree does not bear as

well as Sandersha, nor is the fruit quite as good. The name means

"parrot's beak."

Fig.

20. The Sandersha mango. The fruit is not so richly flavored as that of

Mulgoba or Pairi, but is excellent for cooking. (X 1/3)

Mango.

Cambodiana Group

In

this group the tree is erect, with the crown usually oval, never

broadly spreading, and densely umbrageous. The foliage is abundant,

deep green in color, the leaves medium sized to rather large, with

primary transverse veins more numerous than in other groups, commonly

26 to 30 pairs, quite conspicuous. The odor of the crushed leaves is

distinctive. The panicle is very large, loose, slender, 12 to 20 inches

in length, and laterals pale green to dull magenta-pink, very finely

pubescent. The staminodes are poorly developed, rarely capitate or

fertile. The varieties of this group usually bloom profusely; those

from Indo-China are productive, while the Philippine seedlings in

Florida sometimes bear excellent crops and in other seasons drop all

their flowers. Three to five fruits, or even more, may develop on one

panicle. In form the fruits are always long, strongly compressed

laterally, and usually sharply pointed at the apex, lemon-yellow to

deep yellow in color, with bright yellow flesh almost free from fiber

and of characteristic sprightly subacid flavor, lacking the richness of

some of the Indian mangos. The seed is oblong, normally polyembryonic.

Cambodiana

(Fig. 21). -Form oblong to oblong-ovate, compressed laterally; size

below medium to medium, weight 8 to 10 ounces, length 3 3/4 to 4 1/2

inches, breadth 2 1/2 to 2 3/4 inches; base rounded, the stem inserted

squarely or slightly to one side without depression; apex pointed, the

nak a small point 1/2 inch above the longitudinal apex; surface smooth,

yellow-green to deep yellow in color, dots almost wanting; skin very

thin and tender; flesh deep yellow in color, very juicy, free from

fiber, and of mild, subacid, slightly aromatic flavor; quality good;

seed elliptic-oblong, thick, with short fiber on ventral edge. Season

in Florida late June to early August.

Originated at Miami,

Florida, from a seed introduced in 1902 from Saigon, CochinChina, by

the United States Department of Agriculture (S. P. I. 8701). A later

importation of seeds from the same region (S. P. I. 11645) has given

rise to another variety propagated by budding which differs slightly

from the one here described. The tree bears more regularly than most of

the Indian varieties. Named for Cambodia, a region of French Indo-China.

Fig. 21. The Cambodiana mango. (X 1/3)

The

Mango

Botanical

Description

History and

Distribution

Composition

And Uses Of The Fruit

Climate

And Soil

Cultivation

Propagation

The Mango Flower

And Its Pollination

The

Crop

Pests And

Diseases

Races and

Varieties

Back to

The Mango Page

|

|